Making History

Bakken Receives Western History Association Recognition

October 13, 2009

By Mimi Ko Cruz

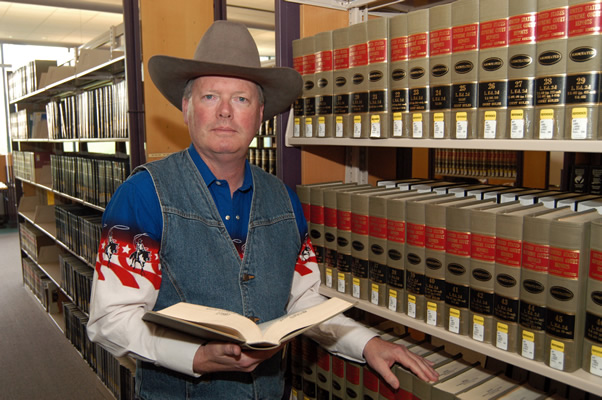

Gordon Morris Bakken

Date of Birth: Jan. 10, 1943

Birthplace: Madison, Wisconsin

Residence: Fullerton

Education: B.S., M.S., and doctorate in history and J.D. from the University of Wisconsin

Family: Wife, Brenda Farrington; daughter, Angela Henderson, of Fullerton; son, Elwood Bakken, of Bozeman, Montana; and grandchildren Erika Lyn Henderson, Emily Grace Henderson and Ocean Chi Kiang Bakken.

Years Teaching at Cal State Fullerton: 40

Fun Fact: Bakken participates in an annual deer/elk hunt in Montana with his son and makes elk meat balls and venison sausage from his game for his History Department colleagues at his home party each fall.

Favorite Quote: "When I get a little money, I buy books; and if any is left, I buy food and clothes."

— Desiderius Erasmus

Favorite Historian: John Philip Reid, for "changing the way we think about the law and culture."

For his contributions to history over the decades, Gordon Morris Bakken, professor of history, has been awarded the Western History Association’s 2009 Award of Merit and honorary life membership.

“Both awards are a big deal in western history,” said Bakken, who accepted the awards Oct. 9 at the organization's conference in Denver.

“Gordon was a unanimous selection of the Award of Merit committee. He has made endless contributions to WHA over several decades, including serving as long-term chair of the Financial Advisory Committee,” said Margaret Connell-Szasz, professor of history at the University of New Mexico and WHA’s award committee chair.

Bakken is the author of 21 books. His latest, published this month by the University of Nebraska Press, is “Women Who Kill Men: California Courts, Gender and the Press.”

Co-authored with his newlywed, Brenda Farrington, a history lecturer at Chapman University, the book examines 18 sensational cases of women on trial for murder between 1870 and 1958. It describes the details of the trials and the changing public image of women.

Some of his other books include “The Mining Law of 1872: Past, Politics and Prospects” (2008, University of New Mexico Press); “Practicing Law in Frontier California” (2006, University of Nebraska Press); “Encyclopedia of Women in the American West” (2003, Sage Publications); and “California History: A Topical Approach” (2002, Harlan Davidson).

Now under consideration at the University of New Mexico Press is a two-volume book titled “Invitation to an Execution” that Gordon has written on the death penalty.

He also is assembling an anthology of original essays, “Activist Minority Women in the American West,” co-edited with Clifford Trafzer of UC Riverside and Sandra Schackel of Boise State University.

Scheduled for publication in 2010 is “The World of the American West,” 20 original essays by Bakken for Routledge Press.

Bakken joined the Cal State Fullerton faculty in 1969. He’s received more than $50,000 in grants underwriting his research projects.

As a senior member of the faculty, Bakken donates cash awards for his colleagues through several programs.

When Thomas P. Klammer, emeritus dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, created the Dean’s First Book Prize in 2008, Bakken donated $5,000. The first award recipient, Terri L. Snyder, professor of American Studies, received a plaque and $1,000 for her book “Brabbling Women” (2003, Cornell University Press).

“I donated to encourage our colleagues in the college as they produce scholarly books,” said Bakken, who also contributed $5,000 to the Arthur A. Hansen Lecture fund in honor of Hansen, emeritus professor of history and former director of Cal State Fullerton’s Center for Oral and Public History.

He also contributes $1,000 each year to the History Alumni Association for the Gordon Morris Bakken Prize, which is given to a colleague who does the most to support students, and another $250 annually to Titan Athletics to support programs that give students opportunities to play sports.

“I give because alumni, faculty and community giving to university programs is an integral part of making CSUF the outstanding academic institution it has become and it is only with sustained giving that greatness as a university can be achieved,” Bakken said.

Usually sporting Western wear and a cowboy hat, Bakken is easily spotted on campus, where he spends many hours teaching and advising students. He has served as an adviser to Cal State Fullerton’s award-winning History Honor Society, Theta-Pi, and it’s student journal, Welebaethan, both well known for being named the best in the nation year after year.

“Gordon is a remarkable professor and colleague,” Klammer said. “As the author or editor of more than 20 books, he has in some years been responsible for a majority of the books published by members of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, and they are a very productive group. He is renowned as a challenging, yet always entertaining teacher — extremely popular in spite of setting very high standards. What surprises many of his younger colleagues is that in addition to being a nationally respected scholar, he is an accomplished outdoorsman, whose annual hunting trips in Montana result in an abundance of elk meat balls and sausages that are always a big hit at the fall History Department party.”

Bakken recently answered a few questions about his academic discipline and research:

Q: What is the value of history?

History can teach society to make more rational decisions about actions to be taken or policies to be pursued.

History helps us to find patterns and repetitions, but also to protect cultural values against the materialism of an acquisitive society. History displays patterns of beliefs, ideals, loyalties and aspirations capable of transforming a random aggregation of human beings into a coherent society. History is part of objective reality and the human mind has an innate desire to explore and understand that reality.

History is a part of cultural heritage and teaches wisdom and fosters virtue to make us better human beings. For each of us, history helps us to understand change and determine self-identity. In studying history, we attempt to realize our human potential, to break out of the constricting circle of the present. We affirm our humanity as well as our nationality. We ask age-old questions about our duty to country, others and self.

Q: What interesting historical facts have you learned through your research over the years?

The most interesting thing I found is that history is largely determined by the times historians write history. Contemporary concerns simply creep into narrative analysis and, the larger the topic, the more likely the historian will advocate a current interest.

My interest in women’s history flowed from the 1960s interest in the history of unrepresented groups. Many of my colleagues at the University of Wisconsin focused on African-Americans, but I started looking into the experiences of women in the American West. I quickly found that women had far more to teach me than any other group of people.

Q: What did you learn when writing “Women Who Kill Men”?

What we found was: newspaper stories, editorials and statements of counsel reveal much about the image of women caught up in California’s criminal justice administration system.

The trials involving middle- and upper-class deceased men and their alleged slayers highlighted dominant cultural norms of the times. This culture reflected the signs and practices of journalists and lawyers represented in words and behaviors.

Victorian values defining the feminine as existing in a domestic sphere, providing for the care of children and educating the next generation in morality came under attack by the turn of the century.

The decade of the 1920s saw a shift in press emphasis, as well as legal defense tactics. Lawyers no longer raised issues of menstruation and hysteria characteristic of the 19th-century expert testimony. Rather, counsel emphasized science and women’s activities and victimization. Reporters continued to focus on dress and female mannerisms. Yet, if the defendant could pass herself off as virtuous or sympathetic, male reporters continued to pander to stereotypical female images. Reporters portrayed women-gone-astray far less sympathetically.

Until the 1940s, reporters portrayed most women, particularly “fat women,” in a negative light. The press warned men to beware of women in general, but used some defendants for moral lessons. The gains made by women in the 1940s and 1950s tempered editorial venom.

The cases of women accused of killing men and their trials have demonstrated that gender mattered. Women and their lawyers constructed contemporary gender stereotypes for courtroom and the press. Women dressing and acting the part of the victim of a patriarchal system or of middle class values was significant. Good "lawyering" was important in the courtroom and with the press.

Courtroom justice was part of the attraction to the reading public and the audience. The rulings of the judges were significant for the presentation of defense and prosecution cases. The law guided the judges in making these rulings. The press commented on the performances of witnesses and lawyers, but seldom on law.

Q: What do you think about the university’s History Department and its future?

The History Department is becoming the most coveted situs for the study of history, particularly world history, in the state of California. The department has hired some of the most exciting scholars I have had the privilege of associating with in my career.