An Excerpt

When the "Jungle" Met the Forest: Public Work, Civil Defense, and Prison Camps in Postwar California

By Volker Janssen

In January and February 1969, winter rains pounded southern California counties mercilessly.

The wettest winter in 80 years caused millions of dollars in losses in the region's agriculture, ravaged canyons with flash floods, and buried roads and freeways east of Los Angeles and neighboring Orange County.

Matters went from bad to worse on Feb. 25 when 6,000 Southlanders fled their canyon homes in fear of mudslides.

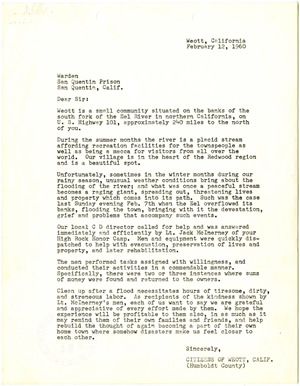

This letter shows support for a California prison camp in 1960.

Many stayed behind, such as the Quick family: mother, father, and their four children. Five of the Quicks' neighbors died in the disaster. Cut off from the outside world for three days in Silverado Canyon on the western slopes of the Santa Ana Mountains, the Quick family was rescued by a team of convicts from the region's prison forest camp.

The Quicks were no "bleeding-heart" liberals likely to mollycoddle criminals. Volunteers in Ronald Reagan's gubernatorial campaign, they supported the Vietnam War and cracking down on Berkeley student protests. But the 1969 flood washed out their law-and-order stand.

Grateful for the "heroic deeds" of the sleep-deprived, soaked and starving "men who put their life on the line for others," Mrs. R. Quick asked the governor in a letter to reduce their sentences.

. . . Such encounters were the result and purpose of California's prison labor camps, which had kept a ready army of inmate so-called volunteers for firefighting and disaster relief since World War II.

. . . . In 1944, Gov. Earl Warren took advantage of flush wartime state revenues and his popularity to replace the Board of Prison Director's old system of penal patronage with a modern Department of Corrections. Within a few years, the prison system of the Golden State went from being one of the worst in the nation to being a national and international model of modern corrections.

Forest labor camps were the flagship of the department's new approach. Blending civil defense with public works, the camps combined the familiar routines of road gang labor with the political appeal of military service. They enjoyed broad public support at a time when the state's bolder therapeutic experiments, such as its therapeutic community projects, remained controversial.

Volker Janssen is an assistant professor of history at Cal State Fullerton. This article is an excerpt from his piece in the December edition of the Journal of American History. The full article is available online.