Preserving A Culture

Fulbright Scholar Returns from Summer in Mexico, Researching Purépecha People

September 1, 2009

By Mimi Ko Cruz

Tricia Gabany-Guerrero

Tricia Gabany-Guerrero, assistant professor of anthropology, has returned from a summer in Michoacán, Mexico, where as a Fulbright Scholar, she made important discoveries while researching a pre-Hispanic civilization.

Over the past three months, she discovered three new archaeological sites and located eight Purépecha language documents, discussing Purépecha perspectives on colonial rule from the early colonial period (1560-1660), in Mexican archives.

She spent her Fulbright summer affiliated with the Instituto de Investigaciones Historicos de La Universidad Michoacana (Institute for Historical Research at the University of Michoacan) de San Nicolas de Hidalgo.

“I learned that the social relations between the Purépecha people and Spanish colonizers during the early Spanish colonial period were very complex and that the Purépecha leadership played an extremely critical role in negotiating how colonization, religious and political, would impact their communities,” the professor said.

Purépecha Pointers

- Purépecha is a language as well as the name of the pre-Hispanic people of Michoacan. The language has no known connections between any other existing languages. “This is one of the reasons that studying Purépecha is so important,” said Tricia Gabany-Guerrero, assistant professor of anthropology. “The Purépecha language currently is being revitalized through cultural heritage programs and there is a need for instruction in California.”

- According to Gabany-Guerrero’s preliminary research results, the Purépecha Highlands appear to be one of the early centers of Mesoamerican culture dating back about 5,000 years.

- From her research, Gabany-Guerrero said she’s learned “that the social relations between Purépecha and Spanish colonizers during the early Spanish colonial period were extremely complex and that the Purépecha leadership played an extremely critical role in negotiating how colonization, religious and political, would impact their communities.”

As a result of her research, she now is completing a book about the cultural history of the Purépecha people of the pre-Hispanic and Early Spanish Colonial periods.

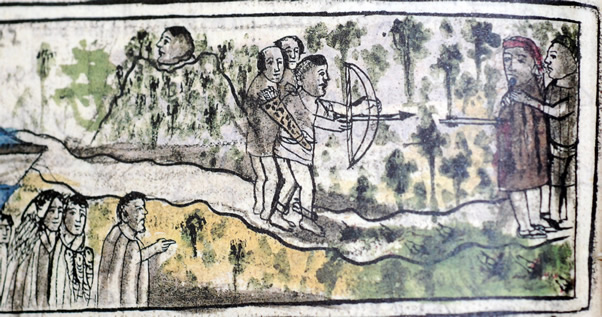

“In general, I am interested in studying how people respond to imperial rule,” Gabany-Guerrero said. “Using early colonial manuscripts written in the Purépecha language and the iconography of Purépecha artifacts and cliff paintings, I am beginning to understand how the Purépecha civilization changed over time and responded to different types of political rule. I am particularly interested in finding out about the ways that communities in the rural highland regions of Michoacán, Mexico related to imperial powers under both Purépecha and Spanish rule.”

She said her fieldwork includes the discovery and documentation of archaeological sites, paleography and translation of Purépecha-language colonial documents, which previously were thought not to exist, and collaboration with contemporary Purépecha communities in Michoacán and in the California diasporas to develop cultural heritage programs.

According to her research, Michoacán was the homeland of the Purépecha people and the pre-Hispanic Tarascan Empire. They were the rivals of the Aztecs, or Mexica, people. They dominated the central-western region of Mexico and were considered the second-most powerful empire when Hernán Cortés invaded in 1519.

“Because Mexico City — the ancient city of Tenochtitlán — was the capital of the Aztec Empire, it soon began to dominate the historical and anthropological studies of Mexico,” Gabany-Guerrero said. “Therefore, many people in the U.S. have not heard of the Purépecha. … The people of Michoacán have a long history in the United States and form a large portion of the Mexican heritage population in California. In fact, Orange and Riverside counties have a large population of Michoacanos, many of whom have Purépecha cultural roots and are Purépecha speakers.”

Gabany-Guerrero began her research in Michoacán in 1989, when she received a summer grant to study there.

“I love working in the rural communities of the Meseta Purépecha with the Purépecha people,” she said. “I have returned virtually every year since then to continue my research.”

As co-director of an international research project that works in partnership with the leadership of the Comunidad Indígena de Nuevo Parangaricutiro, Gabany-Guerrero works with other anthropologists, environmental scientists, geologists, historians and biologists.

“We have been funded by the National Geographic Committee for Research and Exploration as well as the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies,” she said, adding that the researchers worked with community leaders to establish a community museum, mapped more than 75 pyramids and archaeological structures and collected ethnohistorical documentation.

The data Gabany-Guerrero collected during her Fulbright field experience “will provide me with material for producing publications during the next year,” she said.

She expects her Purépecha study will continue throughout her lifetime and she plans to train students to continue the research.

She is working on a project to help open a community museum in Michoacán, cataloging artifacts and creating a potential design and exhibits for it.

Last spring, Gabany-Guerrero created and taught a graduate course on Mesoamerican peoples. She plans to develop a course on the Purépecha next year. Meanwhile, she is incorporating her community museum project into a course she’s teaching on applied anthropology.

Gabany-Guerrero, who speaks Spanish and Purépecha, joined Cal State Fullerton’s faculty in 2008, after earning her Ph.D in anthropology from the University at Albany (SUNY) and directing the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the University of Connecticut. She’s been studying the Purépecha people and language for two decades and is an expert in the field.