Lincoln Walks Again

Reprinted from the Summer 2001 issue of Titan Magazine

By Orman Day

Ron Rietveld is an authority on Abraham Lincoln. Photo by Phil Channing

For Professor Ron Rietveld, bringing a hero to life is his life’s work. Learning and teaching history are his passions.

Abraham Lincoln strode on his long legs again, clacking his size-14 boots against the night-shadowed streets of his Illinois hometown nearly a century after his assassination.

At a second-story window opening onto the Springfield cemetery where the martyred 16th president was entombed, Ron Rietveld–a lanky graduate student in his mid-20s during the summer of 1962–stared into the dark and cleared his throat.

In the sonorous voice of a church choir tenor, Rietveld began to recite the haunting words of Vachel Lindsay’s poem “Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight.”

It is portentous, and a thing of state

That here at midnight, in our little town

A mourning figure walks, and will not rest…

Stirred by the confluence of poetic word and place, his young wife, Ruth — sitting atop a four-poster bed amidst a room full of antique furniture and adornment — felt gooseflesh rising upon her arms as her husband continued:

He cannot sleep upon his hillside now.

He is among us:–as in times before!

And we who toss and lie awake for long

Breathe deep, and start, to see him pass the door…

Like Abraham Lincoln, Ron Rietveld spent a happy boyhood in a log cabin. Rietveldís grandmotherís home still stands in Pella, Iowa.

Nearly four decades after that impish oratorical display stimulated his wife’s vivid imagination, Rietveld continues to draw on his knowledge, passion and sense of the dramatic to bring Lincoln back to life. A half-continent away from that caretaker’s home in Oak Ridge Cemetery, the history professor roams his Cal State Fullerton classroom with chalk in hand to outline the debate tactics of Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, give voice to the president’s Civil War critics and diagram military strategy at Antietam and Vicksburg.

If Lincoln was fated to become America’s greatest president, Rietveld was destined to become an influential Lincoln scholar and inspirational history professor. Their births were separated by 128 years and 700 miles, with Rietveld born at home in Depression-blighted Iowa in 1937. His mother nearly died from complications, so his parents decided to limit themselves to the one child, who was given the first name of a popular Des Moines-based radio announcer: Ronald Reagan.

The first history that Rietveld learned was his ancestors’. The prairie town of Pella was founded in the 1840s by his great-great-great-grandparents and other Dutch immigrants, members of a serious-minded Protestant sect that fled religious persecution and Europe’s “Potato Blight.”

Particularly in the wintry months, Rietveld spent much of his boyhood inside his grandmother’s log cabin.

“She had a dancing stove,” he recalls. “It burned wood, and with the damper open, the air would gush into the stove and feed the fire. The pipes to the chimney would turn red hot and the whole stove would shake, and I’d be afraid Grandma was going to burn her house down.”

At 4, Rietveld was ready for school.

“Mother says that the first thing I told my kindergarten teacher was ‘Teacher, I’m here to learn,’” he recalls. “And, I’m still learning. The more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know. I want to learn it and share it.”

Rietveld grew up revering the Bible, the knowledge awaiting him in the public library, and Lincoln, whose etched image — the world-weary eyes, the creviced face, the patriarchal beard — hung in his bedroom. As a fifth-grade student, he was such a voracious reader of books about Lincoln and other subjects that the librarian graduated him from the children’s section to the adults’.

“I was a teacher at heart as a boy,” he says. “We kids played school, and I had my own blackboard and bell. I taught spelling and history… never math… and I told stories about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. If I didn’t have a ‘class,’ I’d play school by myself with an imaginary audience.”

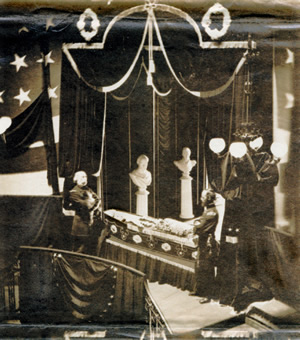

By what he calls “an act of divine providence,” his anointment as a serious Lincoln scholar began during a visit as a 14-year-old to the Illinois State Historical Library. Allowed by the state historian to explore Lincoln-related materials on his own, Rietveld discovered a blurred sepia-toned photograph of a man lying in a coffin guarded by military sentries.

A note identified the scene — Lincoln lying in state in New York City Hall — which the teenager recognized from a line drawing in his own copy of a Harper’s Weekly from 1865.

Rietveld drew national attention upon his discovery of this last Lincoln image. Photo courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

“I knew exactly what it was,” he says.

The teenager showed the photograph to the state historian, who swore him to secrecy until its pedigree could be researched. Two months later, the photograph was distributed worldwide by the Associated Press and published by Life Magazine, along with its history. Bowing to Mary Todd Lincoln’s wishes, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had ordered the destruction of all prints and photographic plates of Lincoln lying in state. Stanton, though, kept a small print, which eventually found its way into the historical library.

When his discovery was chronicled in the local media, Rietveld was introduced to noted Lincoln biographers, and for his 17th birthday, his parents gave him newspapers from 1865 carrying coverage of the journey taken by Lincoln’s funeral train to Springfield.

Rietveld’s choice of college was largely determined by the religious environment in which he was raised. “No work on Sunday,” he recalls. “We visited family after church. I could play outside, but not loudly. Faith was central in the lives of both sides of my family.”

Three days after earning a B.A. in history at an Illinois evangelical college, he married Ruth, a childhood sweetheart. At a Minnesota seminary, he received a bachelor of divinity degree that led to his ordination as a Baptist minister and a summer-long stint as an unpaid chaplain at Utah’s Zion National Park.

His stay would have been idyllic among Zion’s cliffs, canyons, waterfalls, golden eagles and the world’s largest arch — Kolob — except for the day he was called upon to minister to two parents.

“I waited with them,” he recalls, “while a young man’s body was brought down from the mountain.”

Despite the satisfactions of tendering pastoral care, Retvield realized that he was “called” to be a professor at a lectern, not a preacher in a pulpit, and pursued higher degrees in history. His nascent reputation as a Lincoln scholar led to a certain phone call in 1963 when he was a student in Champagne-Urbana, Ill.

The caller identified himself as Norman Rockwell, a painter who was going to create a portrait of Lincoln as a young man.

Only the appearance of the legendary pipe-smoking illustrator in a chauffeured black Cadillac convinced Rietveld that the phone conversation hadn’t been a prank. The party rode in style to New Salem, where Rietveld described Lincoln’s ability to use his long arms to upend wrestling opponents, his descent into despair after the death of a woman he loved, and his self-education in trigonometry and law.

In Springfield, Rietveld told Rockwell about Lincoln’s growing stature as a lawyer and politician, his marriage to Mary Todd and his election to the Presidency in 1860.

Months later, Rockwell sent Rietveld an autographed lithograph of “The Young Lincoln,” which depicted the future president — an axe resting in one hand — reading from a leather-bound law book, with a fence of wooden rails and a log cabin in the distance.

At the University of Illinois, Rietveld received his master’s degree in 1964 and followed that three years later with a doctorate in philosophy, earned with a dissertation on “The Moral Issue of Slavery in American Politics, 1854-1860.”

In 1969, Rietveld settled his wife and two sons in Fullerton and took his place at Cal State Fullerton, leaving behind those penurious days when he scrounged gas money to reach his rent-free accommodations at the cemetery.

For more than three decades now, he has spoken so vividly of Lincoln to his classes that the president seems, at times, to inhabit the very halls of the Humanities and Social Sciences Building.

At 6 feet, 1 inch tall, Rietveld is three inches shorter than his hero, but he does have the same cropped beard without a mustache, so–if one dims one’s eyes — there is a certain resemblance when he quotes Lincoln’s 1863 despair at the Union’s inability to overcome the Confederacy: “I am as powerless as any citizen.”

During a course on Lincoln and his military leadership, students react noticeably to the scenes described by their professor. They grimace at the ineptitude of Lincoln’s early generals, sigh at the personal crises that bedeviled his household, nod their heads at the exactitude of the Gettysburg Address and groan when John Wilkes Booth steps into the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre.

During his youth, Rietveld learned the art of theatrics curled up beside the family’s Zenith radio, listening to serials that always ended with a cliffhanger. He brings that same drama into the personal anecdotes that bridge his students to the past.

As they listen to one of his reminiscences, students can imagine themselves padding through the grass to reach the gravesite of Lincoln’s black valet. William H. Johnson, Rietveld tells his class, accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg for his address, while Mrs. Lincoln stayed home to nurse her son Tad, bedridden with smallpox.

On the return trip, Lincoln — enduring a relatively mild bout of smallpox — rested in the train while Johnson cooled his head with a wet towel. Tad lived, but Johnson caught smallpox and died. Lincoln paid for his valet’s burial in Arlington National Cemetery. And what were the words the president had chiseled into the tombstone? Classes wait expectantly for Rietveld’s dramatic answer: “William Johnson. Citizen.”

Rietveld’s presidential anecdotes aren’t limited to the 19th century. In 1981, he was asked to help document quotes for the speechwriting team serving the man whose first name he bore: Ronald Reagan, the 40th president.

“Once the speechwriters reached me in Holland with a Lincoln ‘quote,’” recalls Rietveld. “I was far from my Lincoln library, but I know Lincoln’s language and the quote wasn’t his. I told them that the quote was ‘spurious,’ but they said that the president liked it. I told them to preface the quote then with something like ‘Lincoln reportedly said.’ Later, Reagan used the quote at the Republican convention without saying ‘reportedly,’ and he was heavily criticized for it in print by a Lincoln scholar. I tried….”

Rietveld’s documentation labors were rewarded, though, when Nancy Reagan arranged for him to visit the Lincoln bedroom at the White House.

If he can quote Lincoln, he can quote biblical scripture, too. Drawing on his seminary theological studies, he’s helping to translate biblical scriptures from the koine Greek of the New Testament era and teaching a course on church history. His training in pastoral care has given him a sympathetic ear as an adviser to campus fraternities, a role that often leads to heartfelt conversations with young men in an office dominated by a dozen somber images of Lincoln in clay and ink. At the intersection of history and theology, he is researching a book that will plumb Lincoln’s spiritual beliefs, including his early skepticism about the miracles attributed to Jesus.

One of his students, Glenna Schroeder-Lein, was so enthralled by his classroom presentations that she became a Civil War historian instead of a violinist. Then, when she was ready to wed, she asked Rietveld to officiate. Naturally, Rietveld — who has presided over the weddings of some 50 couples, including one linking a basketball player with a cheerleader — alluded in his homily to Lincoln, the president’s proclamation of the first Thanksgiving Day and the harmonious truce that ended the Civil War.

Now an assistant editor with the Lincoln Legal Papers Project, Schroeder-Lein recently was reunited with Rietveld, who was invited by the Illinois governor to participate in the Feb. 12 groundbreaking festivities for Springfield’s new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Another attendee was Tom Schwartz, the Illinois state historian, who says of Rietveld: “His love of teaching is evident from the many students he has inspired to pursue careers in history. The public is familiar with historians who advance their own careers through constant public exposure on television or networking among their peers.

“Ron, however, is a workhorse, not a show horse. Because he takes his job of teaching and research seriously, he has little time or inclination to seek the celebrity status that is all too common among professionals. In the long run — and that is what historians are most interested in studying — Ron has profoundly touched more lives than television’s celebrity historians.”

Like Schwartz and others in his field, Rietveld knows that those who forget the world’s blood-spilling history are doomed to repeat it. “I teach history because it’s the story of human life through the ages. Therefore, the lessons of the past impact our present and our future… for better or worse.”

No wonder then that Vachel Lindsay’s poem — the very one that Rietveld continues to recite — ends with a plea to end the spectral walks of the assassinated president:

It breaks his heart that kings must murder still,

That all his hours of travail here for men

Seem yet in vain.

And who will bring white peace

That he may sleep upon his hill again?