Gott Giftedness?

Longitudinal Study Marks 30th Year, Researching Roots of Leadership, Intelligence, Motivation

April 7, 2009

By Mimi Ko Cruz

What makes a leader?

Three decades of research led by Allen W. Gottfried, professor of psychology, has produced an answer: “gifted motivation.”

Gottfried said motivational giftedness, or extreme motivation, applies to those who are superior in striving toward and determination pertaining to an endeavor. It is not the same as intellectual giftedness, which applies to those often considered geniuses, people who score 130 or higher on IQ tests. An IQ indicates an individual’s mental abilities, relative to others of the same age.

“It’s the motivationally gifted who become the leaders,” said Gottfried, who launched the Fullerton Longitudinal Study with a $69,000 grant from the Thrasher Research Fund in 1979, the year after he joined the university. “The path to leadership requires the stimulation and support of intrinsic motivation.”

There are factors that facilitate higher motivation, environmentally, he added. In other words, parents, teachers and others can inspire intrinsic motivation of children through encouragement of persistence, taking on challenging tasks and the seeking of novel experiences.

Unprecedented Research

The landmark study started with 130 1-year-old children, who were followed every six months through preschool and every year from age 5 to 17. They were surveyed again at age 24 and again this year at age 29. Though some of the subjects dropped out of the study, 106, who live all over the world, remain.

Over the years, Gottfried and his colleagues — which include his wife, Adele Eskeles Gottfried, a professor of educational psychology at Cal State Northridge; fellow Cal State Fullerton professor Diana W. Guerin and associate professor Pamella H. Oliver; and students — have produced scores of papers based on the study’s findings. The researchers have focused on intellectual and motivational giftedness, as it relates to education, temperament, parental involvement and, now, leadership development.

In a 2005 journal article, Gottfried and three colleagues compared adolescents with extremely high academic intrinsic, or gifted, motivation to their peers on a variety of educationally relevant measures. They concluded that gifted motivation proved to be distinct to gifted intelligence and the implications laid the groundwork for identifying such students and providing schools the opportunity to develop programs for them.

Gottfried said many school districts have since begun considering gifted motivation, as well as gifted intelligence, when admitting students into GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) programs.

When the study’s subjects were 7 and followed through age 12, the researchers found their results showed that children of working mothers develop just as well as children of non-working mothers.

Today, Gottfried may be analyzing leadership development, but he’s been producing leaders in his research lab for 30 years.

Student Success

Through the decades, Gottfried’s student researchers have included many who have earned doctoral degrees and become his colleagues. They include Guerin, Oliver and Jacqueline K. Coffman, professors of child and adolescent studies at Cal State Fullerton.

Another former student, Makeba Parramore Wilbourn, received her Ph.D. in developmental psychology from Cornell last year and now is an assistant professor of psychology at Duke University.

“The more knowledgeable I become about developmental psychology and the more immersed in the literature, the more I realize how much of an impact the Fullerton Longitudinal Study has had on the field,” she said. “From the day I graduated, I have used the knowledge and skills that I gained from working on the project in every aspect of my doctoral training. When I first started the program at Cornell, I felt like I didn't belong there because I didn't come from another Ivy League or prestigious liberal arts school. But, as time went on, I began to realize how well trained I was and that I was actually starting well above the rest of my cohort in terms of research experience and substantive knowledge.”

"Authentically brilliant" is how Wilbourn described Gottfried, who earned his Ph.D. in psychology from the New School for Social Research in New York in 1974.

He “truly is one of the most insightful, creative and intuitive minds that I have ever had an opportunity to work with,“ she said. “What I am most grateful to Allen for is that he never lowered the bar for me. Being a product of a biracial single parenthood household, the majority of my educational experiences involved people lowering the bar and expecting much less from me, due to my circumstances. From Day 1, Allen expected nothing but the best from me. He didn't see me as a minority student or a commuter student or a continuing education student. I was just a student, his student. When I told him that I had been accepted at Cornell, he wasn’t surprised or shocked, just proud. Again, he expected nothing else. I would not be where I am today if it weren't for the guidance, tough love and encouragement that I received from him.”

Her sentiments are echoed by many former and current students of Gottfried. Besides, Wilbourn, Guerin, Oliver and Coffman, more than 30 other former students completed doctoral programs and are working as college professors and researchers.

“Dr. Gottfried is making new contributions to the field of human development with each year he continues his unprecedented research,” said Thomas P. Klammer, dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. “Such long-term study of the same sample of subjects, from early childhood to adulthood, has only been possible because of his dedication. He has continually rebuilt his team of researchers, many of them students working under his supervision. Most impressively, some of them have gone on themselves to earn Ph.D.s and then returned to assist him in this research.”

Gottfried’s work has been supported by many different grants, most modest in size, Klammer said. “But, often, he has carried on this work without any financial support at all, not even a reduction in teaching load. He is, indeed, an example of a true scientist, driven by passion and pursuing new knowledge regardless of the obstacles.”

That’s because the study is Gottfried’s “passion and professional lifeline,” he said. “I love the study of change over time. As the subjects age, the issues become increasingly exciting. The study is alive and developing itself. We continue to collect data, and the dreams of many students have come true by being part of the study. They have learned how to conduct longitudinal research, collect and code data, analyze a complex databank and prepare papers for presentations and publication.”

No Ending

He said he hopes to continue the study as long as possible.

“Studying a sample for almost 30 years fits my personality and cognitive makeup,” Gottfried said.

Though his plans don’t include retirement any time soon, he has been invited by the president of the Western Psychological Association to deliver a “Last Lecture” at the organization’s annual convention in Portland on April 23.

Gottfried plans to unveil the latest findings in the Fullerton Longitudinal Study and share his student accomplishments and his teaching philosophy.

The title of his lecture is “How Students Became My Colleagues.” (download PowerPoint presentation)

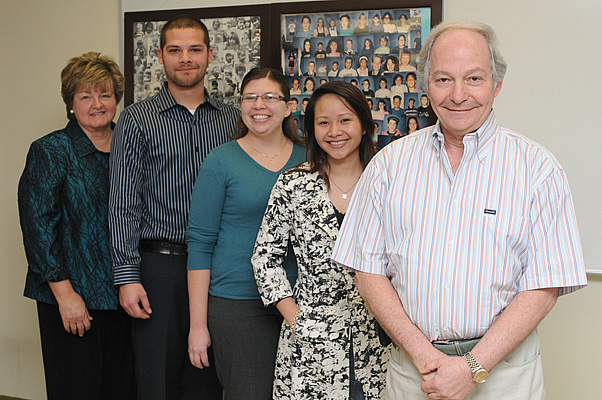

Three of Gottfried’s students — Amy N. Ho, a graduate student in psychology; Anthony Rodriguez, a senior child and adolescent studies major; and Erin Arruda, a senior psychology major — also will present papers based on the Fullerton Longitudinal Study at the WPA convention. Their papers include an examination on the relationship between applying pressure to oneself academically and how that is predictive of postsecondary education; an analysis of parental expectations and how they relate to self-competence, goal orientation, self-perceptions and other self beliefs; and parents’ perceptions and beliefs as related to parenting behaviors and children’s achievement.

"The experiences that I've gained working on the Fullerton Longitudinal Study with Dr. Gottfried these past few years affirmed my passion for investigating these concepts," Ho said, adding that she plans to continue researching as she pursues her doctoral degree. She's been offered admission and fellowships to Ph.D. programs at Columbia University, New York University, University of Maryland, UCLA, UC Irvine and UC Santa Barbara.

Rodriguez said working with Gottfried has "opened doors" for him, as well. He's received various scholarships and will be working as a summer research intern at the University of Maryland.

"Dr. Gottfried has pushed me beyond what I thought I was capable of achieving," he said. "He's amazing. I wonder where I would be now had I not been introduced to him."