Is the Initiative Process Broken?

Political Scientists Discuss Merits of California's Government

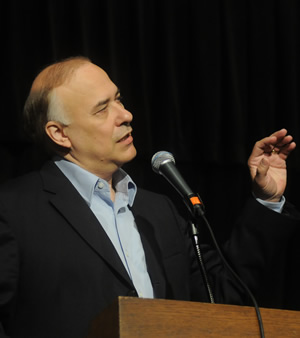

Shaun Bowler

Political scientists Shaun Bowler of UC Riverside and Mat McCubbins of UC San Diego, and strategists/bloggers Jon Fleischman of the Fleischman Group, Flashreport.org, and Jeff Flint of Schubert/Flint, Red County, discussed the merits of California’s initiative process at Cal State Fullerton last month.

The panel was offered as part of a weeklong program “Is California Governable?” held as part of the university’s annual Constitution Day observance.

The panel discussion is available on audio (MP3, 78MB). The following is the event's transcript:

Discussion Transcript

Shaun Bowler: Good morning, everyone. Thank you, Cal State Fullerton, for bringing me down. I’ll try to be brief. I think I’ll say four things, basically why direct democracy is a good thing for the state, and is an unfair scapegoat.

Mat McCubbins

I mean, the first thing I should say is that whenever we talk about this social stuff is that the problem with democracy, or part of the problem with democracy is, there isn’t a traffic light system. There isn’t like a green light to tell you when things are going well, and a red light when things are going bad, and a yellow light to say, well, what’s going on. There are some definitional issues here about what do we mean by what’s good or bad, that are important, and I’m just going to ignore those. That was the first thing there.

So, what’s the second thing? I think the second thing is we’re getting a lot of comment now about how the initiative process bears the blame for current budget issues. And one of the things that people talk about is the two-thirds rule. “Oh, the two-thirds rule is awful. I mean, if only voters weren’t so stupid, if only they weren’t so inept, we wouldn’t have a two-thirds rule and everything would be fine.”

And the thing about that is, it seems to me that voters tend to like the two-thirds rule — and they’re quite right about this — because they know that without the two-thirds rule, their taxes would go up and up and up, and up still. So, the thing that’s stopping people being just taxed and taxed and taxed is the two-thirds rule. So, voters, quite sensibly, don’t want to change the two-thirds rule.

And in fact, that seems to be a property of lots of the initiative process, and lots of things you see in direct democracy, is that voters want certain things, and we don’t like them wanting that. Now, on the one hand, it’s fine for us to say, “Well, voters shouldn’t want this, and voters in a democracy should want something else.”

Jon Fleischman

That’s all fine, but we haven’t really made that argument very well. We haven’t really made that argument — and for those of you, the students, I guess — in a normative sense, about when it’s OK to ignore what voters want. The democratic theory is pretty blank on that one, I think. But, generally speaking, the thing about the initiative process is, it tells us what voters want, and in a democratic sense, that is presumably a good thing.

Which brings me to my third point, which is that there are a couple of things wrong with this, Dave — and those two things are the Democrats and the Republicans. If you’re looking for villains in this piece, then the Democratic Party in the state legislature is one about machine politics, hopelessly corrupt, intent on feeding any special interest, and taxing and spending to the max.

The Republicans are just narrow-minded, mean-spirited obstructionists who aren’t going to be part of any constructive solution for the state. If you want, part of the problem for the state is that Democrats and Republicans are basically a pack of weasels, that’s what they are. Although, as I say that I don’t know if “pack” is the right word. Are they a pack of weasels?

Jeff Flint

Audience Comment (man): Plague.

Shaun Bowler: It’s a plague of weasels? Oh, I was hoping that we’d have a collective noun for that; that is excellent.

The Democrats and Republicans are a plague of weasels, that’s what I’m saying. Now, easy thing; I’m not just talking about the Duvalls of the world. I’m not making cheap shots at Republicans because you could do the same with Democrats. Fabian Nunez, the Assembly Democrat speaker was caught with his hand in the till, padding the expense account. I mean, you get corrupt people in either party all the time, blah, blah, blah, blah.

What it is, it seems that both parties are locked in a structural conflict. There are features of the political system of the state, and American politics more generally, that lock these guys, those Democrats and Republicans into being weasels, into being shoved into pandering for the extreme elements in their party, into running for office, not governing. Which means, I think, given that there are structural problems with California government, it means, I think the initiative process is better than being not bad. Oh, wait, too many negatives.

The initiative processes isn’t just not bad; it’s a good thing, because the initiative process is one of the few things that can save us from the plague of weasels that govern us, because they’re the ones who can say, “You’re taxing us, don’t do this policy, you do this policy.”

We may not like those outcomes. And goodness knows, there are some that aren’t personally frustrated with. But, the initiative process, as a process, saves us from politicians, who are. … let me say this. I’m not saying that the politicians, the choice of word “weasel” is perhaps too loaded. I’m not saying that they’re immoral. I mean they’re responding to structural incentives to behave in a certain kind of way — which brings me to my last point. The other good thing about the initiative process is this, is that when things go wrong — and you could argue they’re going wrong in a budgetary sense now. When things go wrong, we can only blame ourselves. See, one of the characteristics of this current round of crisis that we’re going through, which you see in the paper, ‘oh, it’s the two-thirds rule,’ ‘oh, it’s Proposition 13’; or as I just said, ‘it’s the weasels; oh, it’s all these people.’ But, really, when it comes down to us, it’s us.

We don’t want to pay taxes; we do want lots of services. We want universities like this one of my own, but we don’t want to pay taxes to get them. Now, it turns out that politicians from both parties have told us we can have it both ways for a long period of time. I mean, no politician from either party has been very grown-up about this.

But, in the end, we should know better, you should know better, all of you. You should know better that you can’t have it both ways. And now, we’ve got the consequences of it. But, one of the good things that means in terms of how politics is conducted is that we can run, but we can’t hide, is that the initiative process ultimately means that we are responsible for our own government.

And so, on a number of grounds, I think, we can look around for what we think is wrong with California politics, but what’s most definitely right about California politics is the initiative process and direct democracy.

Mat McCubbins: Firstly, two professors want to stand up to talk. I don’t think I can talk without standing up. So, even though I agree with all of Professor Bowler’s assumptions, I’ll disagree with every single one of his conclusions. In particular, I find the title of the seminar today to be a little ironic, and that is, “Is the Initiative Process Broken?”

Notice it has an emphasis for those of you who want to go on to law school, since I teach law school, that the emphasis is on ‘process.’ Professor Bowler pointed out that the emphasis should be on ‘politics.’ It should be on what we want and how we express our wants, and how we derive those, and not particularly on ‘process.’ He thinks the process is OK.

The emphasis on process dates back to a mid-American legal theory called obviously the “Legal Process Model,” which hasn’t really been in effect for about 30 years. But, we still have an emphasis on process, and in particularly our emphasis in thinking about the initiative process is the beginning of the process.

We emphasize how initiatives qualify for the ballot and how it is that they’re passed. In other words, when we’re thinking about reforming the initiative process our first instinct is to think about changing qualification requirements, changing qualification rules to get initiatives on the ballot, and then changing the majorities we need to pass initiatives.

We’ve done all of these things several times at different levels of government. I don’t think that’s the real problem. The real problem is something that politicians rarely think about, but they think about it a lot more than you and I do; it is something judges never think about when they’re making policy on the bench; and certainly something that citizens never think about, and that is, “How do you implement the policies that you pass?”

The problems that I have with the initiative and that have animated most of my research on the initiative process have been about implementation. Let’s just think about the problem in very simple terms; we’re unhappy with what the plague of weasels are doing, as citizens.

We then either have somebody, some angel, write an initiative for us or perhaps it’s evil Indian gaming lobbyists, or evil education lottery lobbyists to get their own company written into the initiative itself. So, they are the only ones who can sell lottery tickets and lottery machinery in the State of California.

So, you have either special interests getting their initiatives on the ballot or you have angels delivering to you what you want, and not what the plague of weasels want. Fine, you then pass this initiative. Who then implements this initiative?

The very plague of weasels you were trying to get around to begin with. So, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to pass an initiative, and then turn it over to the very people you’re trying to circumvent. If we’re not paying attention to how things are implemented, if we’re not being careful in how we write implementation language, then we should expect the laws not to be implemented.

And we should expect our statutory initiatives, and even our constitutional initiatives, not to be implemented, or at least not implemented in the way you think they were going to be when you either vote the initiative or voted for it.

We’ve looked at initiatives across the country, not just California. We studied, for example, budgetary initiatives, tax and spending initiatives, across the entire country for nearly a 50-year period.

We looked at spending limits, for example. We found it ironic a couple of years ago that Governor Schwarzenegger was trying to pass a spending limit, ironic in the sense that we already had a spending limit in the state and that he seemed to think we needed another one.

But with spending limits we don’t find that any state — with the possible exception of Colorado and their Taxpayer Bill of Rights — has ever passed an effective spending limit. In other words, we don’t see spending change at all, even out to autoregressive efforts of six years’ length.

That is, looking at the effect not just for the next year, but for all of the following six years, we don’t find any effect for spending limits in any state for any spending limit ever passed.

Revenue limits? We don’t find any general revenue limits to be effective. What we do find is that very specific revenue limits, when targeted, for example, at just property taxes — and not property taxes overall but targeted at your property tax bill — then we find that it’s effective for two years.

What you find, of course, is that you get substitution effects. The one with property taxes that Californians all seem to miss — now, maybe this is what we intended — but what we’ve done …

You all are familiar with Proposition 13, right? Proposition 13 limits ad valorem property taxes to one percent of assessed value. Voters can add to that, if they wish, with, for example, Community Facilities Districts and so on, otherwise known as Mello-Roos districts.

So, if you look at your property tax bill, you’ll see that you have one percent and then perhaps these other ad valorem taxes added on it.

But, what we’ve done, because we pulled parcels and looked at the history of the changes in taxes on each parcel, is that we’ve substituted, for ad valorem property taxes, parcel taxes, taxes that are not based on the value of the property but are nonetheless taxes on the property.

When you add that in, it’s not clear that you even get the two-year effect that we found for California from Proposition 13. You very quickly get right back up to the limit, right back up to where California would have otherwise been, had we not passed Proposition 13.

The other problems you inevitably get with initiatives — and you’ve seen this recently. In 2004, we had what — 16 initiatives on the ballot? I quit counting as well. There was a telephone book-size initiative ballot. And that is voters, if you’re faced with that many issues, how do you know how to make trade-offs? Do we want more jails? Do we want more schools? Do we want to regulate nuclear power plants? Do we want 20 percent of our energy to come from wind power? Blah, blah, blah.

Right? How do you made trade-offs from among all those things? How do you make trade-offs across the budgetary implications of all those things? I teach policy analysis; I’m not going to do it. I can’t see how voters would know how to do it.

So, to offer such gigantic ballots to voters, it’s easy to see that it would be hard to make trade-offs.

Second, you’re going to be asked to make trade-offs over time. So, in Oregon, they twice passed limitations on property taxes. And then after they do both of those things, they then require the legislature to spend more of the property tax money on schools. So, over time, it’s not clear how voters are going to make trade-offs.

You don’t follow it for your whole life; you just want one issue at a time. Which gets to my last point; well, second to last point. I’m a political scientist. I’ve one page of notes here I could talk for six hours, right? Brad knows this very well.

And that is you get sequential-elimination agendas occurring quite frequently and you can just look this up on Google when you get back to your dorm rooms or something.

Sequential-elimination agendas, and that means we take one step, and then we take another step and vote for another initiative, and then we take another step, and we end up in a place where we’d rather have not started walking, by the time we get to where we’re at. And so we end up in a place that’s far worse than had we just not gone down this path to begin with.

The last point I wanted to make is that initiatives often give rise to secondary and tertiary effects that we don’t understand. And the tertiary effects, I think, are the most damning. And that is, think about the initial reaction to Proposition 13, and that was the famous Mello-Roos law that created community facility districts, which are property owner elections.

Now, we’re used to elections where citizens get to vote, right, and we’re very careful, right? Just citizens get to vote. Except, in these property owner elections, corporations and foreign entities can be property owners. And in these assessment districts, they get to vote. And so for example, a hotel in downtown San Francisco gets 50 percent of the votes in their assessment district.

It’s odd to have your vote count for one, the hotel count for 50, and the hotel is not actually a person. And so we screw up our electoral process, we screw up the core of our democracy in our reactions to these initiatives, and we don’t think about the secondary and tertiary effects of these initiatives when we’re passing them. So, I disagree, but agree with the core premises.

Jeff Flint: I’m not a political scientist, professor, so I won’t talk as long. I’m a practitioner and I have initiative clients to get back to. My name is Jeff Flint, I am a partner in a public affairs and political consulting firm that has offices in Sacramento and down here in Orange County. I worked for the legislature for 12 years, and then I’ve been in the business of running political campaigns for about eight or nine. Professor D.R. Kiewiet, down there in the audience, was one of my undergrad professors when I was a Caltech political science student. Caltech has a political science program; not well-known for it, very good one. I had Professor Kiewiet and Professor Bruce Cain, when he was there, opposite sides of the perspective. But, I’m going to little bit react to what the two professors said before, because particularly, the most recent instance of their criticisms of the initiative process.

Think about if you remember your Schoolhouse Rock and your three branches of government.

And, in the initiative process, most of the time, in the way the courts have largely interpreted it, is the voters taking the legislative branch of government upon themselves, enacting laws, making changes. The courts have generally frowned on voters trying to take executive authority through the initiative process, and we can get into that a little bit.

But, every criticism that’s made of the initiative process, in terms of not thinking about long-term effects, making a mistake in the drafting, not thinking about secondary and tertiary effects, not looking sequentially over the cumulative impact of different changes over the course of time, those are all the exact same criticisms that we can have of the pack of weasels in the legislature.

Because having worked for the legislature for 12 years before being out as a private consultant dealing with these issues is — I mean I could give you, and we can all think of them or you can read the newspaper headlines, tons of examples of laws passed by the legislature and the pack of weasels with unintended consequences, errors in drafting, not thinking about the long-term effects of this.

I mean, the energy crisis if you remember earlier in this decade. I was actually working in the legislature when that bill passed, and at the time it passed nearly unanimously and all the legislatures were patting themselves on the back thinking what a wonderful thing they had done. They were the cutting edge of energy policy in the nation. All other states were going to adopt an energy plan the way California did, and “Aren’t we great?”

Two years later the state is bankrupt; and in the energy business, you had a governor recalled over it. So, that was not passed by the initiative process, that was passed by the legislative process. So, the problem is California is a big state. In fact, the point I wanted to make before I sit down and let Jon talk and then we get into questions and discussions, is this is part of the series that says, “Is California governable?” I think that’s the real question. The question, “Is the initiative process broken?”

I don’t think that you can say that it is. I think any process that attempts to govern and have the government involved in such a big part of everything that we do is inevitably going to appear to be broken, whether you’re passing the laws by a pack of weasels … I completely agree with the first professor who talked about all of the inherent problems and how we elect the legislatures. They get to draw their own districts. They get to give their voters goodies to get themselves re-elected.

I’m not a fan of term limits. Most Republicans are. I am a Republican and relatively a conservative one. If you didn’t Google me, you can Google me later. I’m not a big fan of term limits, because I think legislatures think — it creates a system of legislatures where the day they get elected to the city council they have a third year political career mapped out about how they’re going to be in the city council for two four-year terms, and then six years in the Assembly, eight years in the Senate, and then eight years in the down ballot Constitutional Office, and then eight years of governor, and then eight years as president.

I mean every single city council person has that 35-year plan mapped out in their head of how they’re going to be president after going through all the term limits chairs. It’s crazy, because they’re not thinking about what they need to be doing to fix the problems in the state, they’re thinking about how to make the right political decisions to keep donors and voters happy so that they can continue to move through the chairs for 36 years and be president.

So, there’s a lot of problems with how we elect legislatures, and ultimately we have a legislature process. It either will be done through the legislature or when the voters are unhappy with the legislative process, they will take that power to themselves as our Constitution allows. Frankly, if you force me to choose between whether or not I trust the voters or the legislators with legislative authority, at the end of the day, I think the voters get it right more often then the legislature does.

So, is the legislative process broken? Every single one of them, and maybe we’ll talk about them some more in detail of the proposed fixes, is basically taking power away from the voters and giving it more to somebody else. If you trust the legislature, if you trust the governor, if you trust judges, if you trust bureaucrats and elected people to do a better job then you trust yourselves, then you can support those.

But, I think at the end of the day, despite some of the problems with the process as there will be with any process, I think the voters get it right more often then the legislatures and the professional politicians do.

Jon Fleischman: Hello. I have the privilege of being the last person to speak. Also, I think I have the privilege of being the only alumnus of Cal State Fullerton to be on the panel, so that’s a novelty. I am also a practitioner. In 1998, I was the campaign manager for Proposition 227, which was about a measure that said, “Children in public schools should be taught English in English, as opposed to being taught English in other languages.” So, we passed that measure with 64 percent of the vote after the State Legislature was unwilling to consider any kind of legislation like that in the Capitol, which probably frames probably the most significant issue that we’re talking about here, which is that the initiative process exists today because special interests in Sacramento dominate a process there.

At some point somebody — I think it was Hiram Johnson — thought it would be a great idea to have a change in the system so that the people would have an ultimate trump over what happens in the legislature. Back in the day when the initiative process was placed in the State Constitution, I believe — and the scientists up here can correct me if I’m wrong — I believe it was the pervasive influence of the railroads, or one in particular that were controlling state government. Now, you’ll find as you go on, that there are other special interests that have replaced them.

I believe that by and large California voters as a group — I’ll bet every individual voter has their own opinions — as a group tend to be more centrist, sometimes center left, sometimes center right, but definitely more centrist in a state where we have a State Legislature that has for decades been dominated by the hard left.

I believe that the result of that has been that the initiative process gets used as kind of a corrective measure by the people when the legislature either does things that people think are too extreme, or the legislature doesn’t respond to problems because the problems perceived by the people aren’t perceived as problems by the people out of the mainstream in the State Legislature.

I guess I could use a couple of examples to kind of walk everybody through that. Probably some of the most specific examples would be Proposition 13, which was discussed earlier, which was passed back in 1978. That was passed I believe, and if you go back and look at the literature that was used at the time and the issues that were presented before the voters. Clearly that was presented as an issue of governments getting too big and spending too much, and your taxes are going higher, and people should be able to depend on the fact that if you own a home that the government is not going to tax you out of your home.

It was passed by the people; again that kind of policy never would have come out of the State Legislature. It raises an issue that was discussed earlier, which has to do with the fact that when you do this kind of ballot box policy enactment, you end up with a process that is not as considered as the one that would normally be taken up by the State Legislature.

For example, Proposition 13 not only limited property taxation, but it had a huge shift in the way that the funding took place period. It forever changed the relationship between the various levels of government, cities and counties versus the state, and all of that.

Of course, when the people pass a ballot measure it becomes out of the hands of the State Legislators to deal with. In other words the State Legislature not having tackled the problem, allows the people to get involved and send in a new policy, and then that policy can only be changed by another vote of the people.

So, where you may have some consensus that there are parts of say Proposition 13 that maybe should be rejiggered and maybe weren’t done right, or maybe tweaked in order to adjust them because of what was the tertiary effects that came into place. It becomes difficult to do, because you would have to take another ballot measure to the people, and the process of doing that is very expensive — or you get measures that are placed on the ballot by the legislature, which is always dubious when the pack of weasels, plague of weasels, whatever it is, the scoundrels in Sacramento.

When they place something on the ballot, not always, but often times it is viewed with a little bit of a jaundice view from the voters. This last May would be a great example, where the governor and the legislature got together and decided that the people of California wanted to increase their taxes to the tune of $18 billion, along with a bunch of other things.

And the people clearly did not want to do that, but it didn’t keep the legislature from placing it on the ballot. But, there are lots of examples of measures such as the big, huge light rail … there was a high-speed rail ballot that passed, I think it was last year or the year before, that was placed on the ballot by the legislature.

And it passed, which highlights … and maybe I’ll finish on this point. I’m not a political science professor, so I can’t take a page of notes and turn it into six hours. I’m doing better; I’m taking no notes at all and turning it into 10 minutes. But, the initiative process itself, I won’t say the process is broken, but I will say that the process has challenges, and it has flaws because again, when you do ballot-box policy, it means you’re taking largely complex issues.

I mean obviously, there are some issues that are less complex. If you have a ballot measure that simply says, I don’t know, “Marriage shall be between a man and a woman,” it’s one sentence and the people get to decide on it. And it is what it is, and you could be for or against it, but it’s probably not too difficult to implement that, although it has its own challenges. What about the people that were married before, what about … and all that kind of intricacy.

But, a lot of these measures are very complex and presenting something that complex to the electorate is a challenge because most people believe very wholeheartedly in the democratic republic system that we have, the idea that, “Hey look, you know what, once every two years, I’m going to look up and figure out who wants to represent my party on the ballot, and I’m going to cast a vote for that person I agree with.”

And once every two years, I’m going to vote in a general election. Someone’s going to win, someone is going to lose. But, I’m going to go back to doing what I do. Whether I’m a student, whether I’m working in the business, whether I’m retired and enjoying ESPN, whatever it is, I’m going to go about doing what I do, and let the people that I elected deal with setting policy for governing my city, my state, my country.

And what happens is when those people are asked suddenly to participate as legislators, it becomes very difficult because they don’t have — not they, ‘we’ — we don’t have the experience and maybe all the education to understand the issues completely. And to make it worse, try to get educated on it, if you want, is very difficult because what’s in the ballot pamphlet is often very difficult to understand.

And then advocacy groups on both sides of the issues make everything incredibly difficult to understand. I mean, I watched with disbelief in this last election; some firefighter is at home playing ball with his kid in the lawn and saying, “If you don’t support Proposition 1A, the state is not going to work any more.”

Translation: what he wasn’t saying is, hey, we need to have a conversation — do we want to raise taxes to get out of the hole that we’re in or not. The point I’m making is that the advertising isn’t always designed for the purpose of educating; as a matter of fact, I would argue it’s designed for the purpose of influencing how you vote. And those are different things sometimes, unfortunately.

So, I will finish where I started by saying that the initiative, the plethora of initiatives that we’re dealing with are a symptom of a broken system that we have in Sacramento.

And I guess I would say … I didn’t mention earlier, I’m an elected officer of the California Republican Party, and I would actually close by saying that my political party is severely disadvantaged in California because of the existence of the initiative process. Even though I participated in it, the reality is I would be much better off if the only outlet for responding to a very liberal state legislature that is not in touch with the people would be to simply change who’s in the legislature.

But instead, that doesn’t happen because before the people can boil over and say, “Those guys are nuts, those guys are too far to the extreme,” somebody comes along with a ballot measure on whatever the issue was that has motivated the voters and gotten them upset. And the people solve it, and in doing so, take the pressure off of those people in the legislature who are extremely … continue to do what they want in those areas that have not been tied down by the people.

And I would thank you very much for the opportunity to share some remarks.

Moderator: I want to thank all of you for your comments. I’m going to go through a couple of questions, so people, think of questions. We’ll find a way to bring a microphone around there and have you ask a question for the panelists. But, I want to start just by bringing a couple of the themes together and a couple of questions that came to my mind while listening to all four of you.

One is going back to the phrase of the day, which is the “plague of weasels,” which is something that you’re going to incorporate into all your lectures now.

This idea that the alternative for the initiative process is a legislature that, as one of the later speakers mentioned, one of the reasons we have the initiative process is because the legislature was viewed and corrupt and bought off in a different historical era. We now have one that’s a little bit more extreme, and you see the play of money.

One of the criticisms of the initiative process is that to get something on the ballot, to get something passed, to go through all the advertising, to persuade and to influence as opposed to educate, you need money.

So, the same groups that are going to influence the legislature to turn them into a plague of weasels are going to influence the initiative process to turn it into the exact same thing.

So, is there a difference between the two? Or has money corrupted the initiative process the same way it would have corrupted the representative democracy process?

Shaun Bowler: Well, again, I made some reference at the start — I think the size of California government has corrupted the legislative process, and the legislative process is both the legislature itself and the initiative process. You can’t expect to have a government that spends in its general fund — at least it did before the current recession — about $100 billion, and, through special funds and others, much more than that; an entity that spends about a quarter of a trillion dollars when everything is said and done and tells every business how to operate, every person how to live their life, you can’t expect people to not attempt to use their money and their votes to influence that process when it’s making decisions basically about everything.

Why would you expect teachers to not band together and form an association, and raise money from themselves to try and influence legislative policy when the state legislature or the initiative process dictates every decision about how we teach kids?

How would you not expect property owners to band together and try to do something about high property taxes when that avenue is available to them?

If the government is going to be as big and pervasive in California as it seems to be right now, much to my personal chagrin, you can’t expect money and voters and other interests to not try to influence it.

So, asking if money has perverted the legislative process — I actually think it’s the other way around. I think money is involved in the political process in general because of the size and scope of the decisions that the government is making.

Mat McCubbins: I’ll make a comment real quick, because it goes to this whole issue of is money corrupting politics. I again would argue money is a form of free speech. Money is a mechanism by which people engage in the process. I would ask for a show of hands in here. How many people in this room have written a check of any size from $1 to $100 towards a political campaign in the last year?

This is in the year of Obama and everything going on with grassroots fundraising. The point being that the reason why “special interest money” I believe is so pervasive in politics today is because we have a culture where the general public doesn’t get engaged and involved supporting the candidates and causes they believe in.

Frankly, it wouldn’t take much. If every regular citizen of California said, you know what? I’m going to give $10 a year to an initiative or to a candidate that I believe in.

You know what? That would absolutely cause all of the money from all of the special interests to be a blip on the radar screen. It’s like we’re complaining. We the people complain about the influence of the money of those interests, but the reality is we’ve ceded the playing field as citizens to those people to dominate the process because we don’t choose to get involved with it ourselves.

Audience Question (woman): My name is Shirley Bloom. I maintain that the process itself is broken both at the legislature and the initiative process. The misnomer, I believe, is saying that the initiative is the voice of the people. It isn’t. It’s a couple million dollars to get an initiative on the ballot. So, right from the get-go it comes from special interests, and they’re the ones who have the law written for their interest. And left from that it gets to these very deceptive commercials that do not tell the truth about the initiative. So, the more money that’s involved, the chances are that the special interest will get the initiative passed or not passed the way they wanted.

Proposition 13 was not the poor property owners, the money didn’t come from them. It came from the wealthy business property owners, and so, there’s the broken initiative process. The legislature is even more a mess, but the process in the legislature allows for open meetings, for compromise, for specialists to get an opportunity to offer opinions.

So, there’s at least a reason, for the theoretical process behind the legislative system. Government was not set up in this country as a direct democracy, it was set up as a representative democracy, and I’d like to hear some response to that, please.

Jon Fleischman: Yeah, I mean, what you say by the way has a large number of academics who would agree with you on this, and a large number of commentators would agree on that. Peter Shrag, for example, and Debbie Brode, Will Knox agree with your view. I think I made two basic ones. So, the general sense of the academic literature that is for research on this, no people, it’s hard to fool people with money and it’s hard to buy your way into a result of a initiative process.

You can use money to get a proposal to the voters, but that’s not enough to get it passed. The voters are often smarter than you give them credit for or want to give them credit for, and they can sort out some of these things.

So, yes it’s a reasonable and plausible argument that a lot of people support, but so far as we can tell a lot of the academic research says no, it doesn’t really quite work that way.

The other point about the representative government is back to this principle again. And as I say this I realize that I myself am weaseling a bit on this one, which is to say that the California Constitution says that it’s the people who are sovereign, not the legislature. It’s our government, it’s your government, and it’s my government, it’s not their government.

And if that’s the case, then why would we grant all this authority to a bunch of people in the belief that they know best. Now, they may know more, they may know best on lots of things, but sometimes on some issues we know what we want and they won’t give it to us.

And so yes there is this talk of David Broder, for example, the journalist who is very big on the Republican form of government. So, you have good company there. But, part of the difficulty there is that the constitution says it’s “our government, not anybody else’s.”

Jeff Flint: Yes, the California initiative process, as Jon’s probably heard you say 20 times over the years is un-American in the sense that it’s … Madison set up a system of checks and balances in our Constitution. The state adopted very similar forms of government to that, and the initiative process in California — unique in the world, as far as we can tell. It’s the only initiative process that has this structure, is largely unchecked. We have this slight check by the judiciary, and as was mentioned, the judiciary is not often taking up ballot measures and rejecting them as being inconsistent with either the U.S. or the state constitution. So, there aren’t any checks and balances built into how the people make law. And it’s either the people through the initiative process, or the people through elections, electing legislators making law. Yes, the people are sovereign. But, the legislature is checked; the people through the initiative aren’t. And so it’s, I’ve always said that the California initiative process is un-American.

I always hear, every single time I ever talk in public, somebody says, that, well the legislative process sucks too, the legislative process is terrible. You should see what goes on in the Legislature. Sure. There are lots of these challenges and problems in making law. The issue is not, should we get rid of the initiative process, but should we adopt one that is more reasonable, that has better features, better qualities, that can perhaps do better at representing what the people want. And, we have lots of examples from around the country and from across the world, of different initiative processes.

And, again, when we get down to local initiatives, particularly for these assessment districts, and local referendums and so forth, non-citizens get to vote in those things, creatures of the State — corporations — get to vote in those things, and so, that just strikes me as broken from the beginning in terms of being un-American. Not one person, one vote. It’s one dollar, one vote, or something like that.

Shaun Bowler: I was going to get into a debate about assessment ballots, but I don’t think we need to do that here. It’s also a flawed system to have people that own property, whether they’re from here or not, having taxes put on them without having a say over your own property. Something like that.

Audience Question (man): I’m either blessed or cursed with a Cal State Fullerton M.P.A., perhaps leads me to make a brief observation and a short question. The observation is the amount of money that’s in the initiative process, typically ten million dollars if you look at both sides. Twenty million dollars is routine within the lifetime of students in this room. We’ll see a hundred million dollar initiative in this state, including out-of-state money. Proposition eight got 12 million dollars came in from Utah. And virtually all of that money is multinational corporate money. It’s not the people’s vote. This is corporate interest money that is getting them on the ballot and then keeping them on the television to get them passed. So, an observation.

Then the question. Do any of you see any hope in the redistricting process that is coming, that, being more geographical and ideological, might give centrist candidates a chance to be both nominated and then elected? That might make, in the long run, our legislature more responsive, and there will be less impetus to use the initiative process to break through the ideological blockage that we have in Sacramento.

Shaun Bowler: Well, I mean, most of the people here are aware of the fact that the voters, through initiative, last year, did pass Proposition 11, which will change the redistricting process for the State Legislature. It exempted Congress, although there’s now a measure seeking, gathering signatures to include Congress in that process at this point. It’s unclear, ultimately, what the conclusion of that will be, although it seems clear that the lines, I mean, frankly they can only get less partisan than they are now, and then we’ll just have to see what happens with the process. I happen to believe that until you can reform this inherent problem with the public employee who is dominating the election process that it is not likely to have a substantial impact on what happens in Sacramento; at least, not on the short term.

And then the only other thing that I would say as an ideologue on the right is that, be careful what you ask for because a centrist legislature may not want to grow as much as a liberal legislature but frankly, it’s not going to shrink either. And I think it will continue a slower pace of growth until you can have a legislature that is full of people that understand that America is about having a limited role for government.

Audience Question (man): I’ll make a comment on money, which is, people get upset about the amount of money in politics. There’s always the sticker shock. I mean, we’ve had these hundred million dollar campaigns and so on. But, I think part of it is just that politics cost money. I mean, I don’t know how much you expect it to cost to run for governor or run a statewide company. But, it will cost a lot of money to do that. Politics isn’t free, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re running for student government here on campus or city hall or whatever. It takes a lot of money to do that and when you start dividing these things out by the population, so even a hundred million dollars, it means the campaign will be spending two or three dollars per head to reach them all. It’s kind of an expensive process. Actually, you guys could probably say how expensive it is to reach a voter. You may notice somehow.

No, no, no. It’s an expensive business and a lot of people don’t know it. But, we get sticker shock thinking of, oh, that costs ten or twenty million dollars. That’s got to be corrupting.

I don’t find that for me, anyway, a helpful way of looking at it because it focuses on the dollar amount, not on the actual event or process that’s happening. I mean, asking these guys to talk to thirty six million Californians, it strikes me as just, off the top of my head, it’s going to be a lot of money. I don’t know what it is, but a hundred million dollars sounds pretty reasonable to me if you compare it, for example, to something like a McDonald’s budget or Pizza Hut budget who are doing the same thing. They are reaching to consumers across the state to tell us about their pizza or their burgers. The difference is, of course, we like pizza and burger. We don’t like what typically is politics with these guys. So, they’ve got some resistance to meet. But, I think the money is a bit of a red herring.

Yeah, it is. There are lots of big money donors from corporations and so on. But, you know, I think Jon’s point at the end about well, part of the problem here is people don’t like politics and don’t engage in politics, and so some of the political ground is ceded to corporations. I’ll say one point is, one of our difficulties, and this shows a point where Mat was exactly right, in our collective attempt to regulate money in company finance, you can see it in candidate elections. We think money is corrupting. But, what we’ve got now is a system where basically only millionaires can run and win for certain offices, not people like us. And we did that to ourselves because we don’t like money.

So, to me, I think the money is a bit of a red herring. If there are points about grassroots campaigns or how progressive units can best use campaigns or get involved, I think attention might be best served by trying to think about different things than the money.

Mat McCubbins: And I think this has been mentioned. It’s also a red herring in two other respects. First, it’s not corporate money, it’s often times union money, but maybe you consider that to be the same thing. And second, Americans are pikers by comparison to other countries. We spend virtually nothing on our elections relative to, say, Japan. It’s just nothing. I mean, they spend five or ten times as much as we do. Last time I checked, it was ten times as much, per voter, as we spent.

Audience Question (man): While I work my way up, I’ll ask one of my own. Let’s pick up on the theme we did it to ourselves. Take Proposition 140 — I mean the number wasn’t that great on the political side to sell term limits. So, in a sense, what about the aspect of, we’ve done it to ourselves, we’re asking voters to change the very system of governance with things like Proposition 140.

Matt McCubbins: I would certainly speak to Proposition 140, of which I was an advocate at the time. And unlike my friend Jeff here, I’m still an advocate for term limits, not because I like term limits, but because I view them as a necessary evil. But, the reality is the broken system in Sacramento, and the solution to that is complex. And where term limits caught fire all around the country is, it was a very simple notion for a voter to understand. ‘I’m going to take retribution against people in government who are scoundrels, and I am going to hurt them and I am going to cause them pain and I’m going to change the system with very little consideration of the long term effects.’ But, I would just submit to you that the voters are never going to undo term limits until they’re convinced that if they undo term limits, something else has happened to the system so that they are not rewarding the people that they don’t like by saying, “I don’t like you,” it’s counterintuitive, “I don’t like you, so I am going to give you more time there.”

And so at some point, the only proposal that’s going to undo term limits is one that comes packaged with reforms of the process where an informed voter can say, “Well, I can understand having longer terms makes sense if you have a system where the unions don’t control everything or if you can have a system that says, “Hey look, there’s going to be a spending limit. There’s going to be other things that are done.” But, that having been said, the notion that we did it to ourselves, it kind of gets to a bigger, more challenging question which is, who are the kinds of people in America that run for public office and who seek these offices and who pursue them and who gets elected.

Right. And who gets elected into those offices, the reality is in a large measure, especially once you start to get in that weird area below Congress and above city government, most of the people in the legislature are former staffers or former union employees. It’s like, normal people who should go, the Mr. Smith who goes to Washington, never seems to run for office. And the process itself has become ugly. If you have had a speeding ticket when you were sixteen years old, the next thing you know you’re attacked and mailed pieces for having been a scofflaw who, from a young age, didn’t respect the law and it goes from there. Part of the challenge that we have is that the system is suffering for lack of civic engagement by people who care. Whether it’s the lack of political giving, the lack of involvement, the key to a representative democracy working, and I can go to the top flow and all this, you need to have good people, in a country that’s made up of good people who get actively, civilly engaged in the process. I believe that what we’re seeing today is a result of, over time, most of the really good people checking out and letting the people who all have agendas dominate the process.

Audience Question (woman): I was wondering about the process of the difference between the Constitutional amendment initiatives and the legislative statute amendments. Both can be, the legislative ones can be tweaked and fixed when they find out. The Constitutional amendment ones pass with the same fifty percent plus one, even though you might have a turnout of 25 percent of the voters. They’re putting in a constitutional amendment. Our state has, what, over 500 constitutional amendments? Whereas the United States Constitution has less than 30.

Should there be a difference in the amount of voters that need to a pass a constitutional amendment as compared with the initiative statute?

Jon Fleischman: The California constitution looks like the Colombian constitution, where they have also passed a very large number of constitutional amendments through the initiative for very similar reasons. They need to get around a legislative process that they can’t get access to. The only difference is the qualification requirements between statutory and constitutional amendments. The different states have different processes, and so we could in fact, for example, have a sunset provision on constitutional amendments.

There are lots of ways to control these differences. You could require that the legislature, as in many states, not amend statutory initiatives for two years, and then they can amend it, reject it, whatever after two years.

Constitutional amendments — one thing that is often brought up — I think it was on the ballot in Arizona last year or the year before? — was to have sunset provisions on constitutional initiatives so that the voters have to take the constitutional initiative up again five or 10 years later, and reenact it, and then have it reenacted every 10 years or so to make sure they still like what they’re doing.

There are a large number of Midwestern states — Professor Kiewiet probably knows better than I do — where it’s actually required to be put on the ballot every decade a question before the people whether they want to call a constitutional revision or not.

So, we see a lot of constitutional revisions in the Midwest, where again, in California, we’re just much different. The whole process is much different.

One of the core problems in California is that legislative districts are gigantic, and so it is impossible to get a more centrist or an even number of elected officials from each party because the districts are so enormous. It takes so much money to run in them, and they’re larger than congressional districts.

So, it’s just very difficult to think about all of the problems we’ve created for ourselves. We’ve not increased the size of the legislature. Lots of other states have. We’ve compounded term limits. We have a two-thirds vote on the budget. We have Proposition 13. We just piled on a number of things, and it’s not clear in the end what that pile produces.

I don’t know how you get to a good place from where we’re at once we’ve put all these restrictions on ourselves through the initiative process, principally, in California.

Jeff Flint: I do think, though, that the point that Jon made relative to term limits applies to any of the proposals that are out there to “fix the initiative process,” which is the voters fundamentally view that as their safeguard against a political system and a legislative system that they don’t view as serving their interests. So, you could put any of a number of these, with all due respect, scholar-generated proposals to fix the initiative process on the ballot. The voters get the first crack at it, and they will reject them.

It’s the same reason that Jon’s absolutely right about term limits. I’m not a fan of term limits, as I mentioned earlier, but I understand why they passed, and I understand why any proposal, particularly one that’s generated out of the legislature to “fix term limits” is doomed to fail.

The same reason any proposal to fix the initiative process in the current political climate is doomed to failure because the voters will perceive it as a flawed legislative and political process trying to take away their one avenue to correct mistakes and enact policy when they feel like the legislature is not addressing their needs, their desires, or their wants.

So, proposed direct legislature will review initiatives before they go on the ballot or fix them or tweak them. Ask me, as a practitioner, which side of that campaign I want to run and it’s pretty easy.

I’ll be on the no side and I’ll do it for free and I’ll win, because of the way the voters would view that. It would be the easiest campaign I’d ever run, is to run the no side of a legislative

Audience Question (man): Yes, the constitution is bonkers, with all these little changes and some of the ideas that Mat talked about really are worth, well worth considering. Much as I like the initiative process, I think these are thing to consider. The other thing is, back to the term limits, it’s kind of — my sense is that the Republican Party’s getting off blind here. I want to come back to the two weasels here.

One is, I think one of the big reasons for the Democrats is that Willie Brown was a smug, condescending machine politician who ran the Legislature, and basically it made rude gestures to California voters. Willie Brown is like the poster child for why we have term limits in this state. He was an arrogant, overwhelming, borderline corrupt person. So, the Democrats have got a lot, you know, much as they kick against it, man you should have fired Willie Brown. You should have put your own house in order. But, and I agree with what, you know, Jeff and Jon are saying about the role of campaigns and governance performance and so on.

Part of the difficulty there though is the Republicans do have their share in this story to blame because they’ve got nothing good to say about government. Nothing. The only good government — you know, there’s no such thing as a good government.

They’ve got this fairly strict Libertarian version of what government does, and I think that gives them problems in terms of advocating reform or wanting reform. But, they’re sort of locked into the — they’ve become part of this sort of endless critical dialogue about state politics rather than offering constructive solutions to the problems.

So, I think they’ve got their own problems just as the Democrats have, I suppose. So, I’m quite happy beating up on the Democrats for why we have some of these things, but the Republicans don’t have clean hands either.

Jon Fleischman: Well, I mean, just a quick reaction on that is, you know, there’s no doubt that the poster child of the term limit movement in California was Willie Brown, but it doesn’t explain why term limits passed in you know, however many other states that have passed it, in quite a number. And maybe California has the worst term limits law.

Moderator: It varies. So, the Republicans liked it in Democrat states and Democrats liked it in Republican states.

Jon Fleischman: Sure, absolutely. It was a blunt tool to fix a problem that was personified by Willie Brown.

Jeff Flint: It’s very simple for the electorate to understand, and very difficult to diffuse.

Jon Fleischman: And although I consider myself to be a pretty conservative Republican I don’t consider myself to be a Libertarian Republican, but we’ll have that conversation on the side.

Audience Questions (man): I agree with the explanation that was presented as to term limits, why it got passed of course as sort of a punitive action. If you believe that, and it’s even going further now, you have people entirely frustrated with Sacramento saying we should further punish them and make it a part-time legislature. I don’t think that any of you would think that’s a good idea, but considering that’s the sort of emotional stuff that voters go for, I’m surprised at the level of support coming from the panel for the initiative process, especially when many of you have sort of justified money and politics as you know, red herrings.

Of course special interests are going to represent their beliefs if they can. So, it just seems an interesting line of logic that special interests are not the evil that many make them out to be, and civic engagement is at an all-time low, and the voters have checked out of the process and have no idea what’s really going on, and vote emotionally rather than rationally.

If you believe those two things, how can you defend the initiative process, or how can you not think it’s broken?

Jon Fleischman: I mean, we had, you know, the initiative process was adopted about what, 90 years ago now? I mean roughly, and you know, the complaints about the initiative process are relatively recent in the political history of California. So, if the initiative process itself was fundamentally flawed … well, go ahead, you guys. We all tend to view these things maybe temporally, so I’m sure there were critics of the initiative process the day after it passed.

Right, so to me personally — and this is probably a little bit of a clue on my personal political philosophy is the full-time legislature in California and a full-time professional careerist-hack-dominated legislature in California is to me sort of the line of demarcation. And when the state started heading in the wrong direction and where the voters in reaction to that have turned voters and quote-unquote special interests, which is not a term I particularly like because everybody is a special interest. Just some people are maybe more efficient at banding together to pool their political power through money and association. But, like Professor Kiewiet just said. We have an initiative process for 90 years. For three-quarters of that, it was rarely used. There were not necessarily significant and far-reaching initiatives and constitutional amendments like we tend to have on the ballot now. And, like I said, my personal view is when you went to a full-time legislature is when the legislature starting going downhill and, therefore, the voters have had to turn to the initiative process more often. So, it’s hard to argue that the process is flawed when it “worked” relatively well for 70 years and it’s not worked well, as some people like to say, for 20 years.

Something else changed about California and not the initiative process that’s caused the angst over it. And I think it’s, whether you agree with me or not on whether or not it’s a dysfunctional full-time legislature that’s wrapped up in itself rather than the real issues that California needs to confront. It’s the other thing that needs to be fixed and not the initiative process. Whatever the other thing is. You can pick your own other thing. Audience Question (man): Yes, it would be interesting to hear from the panel whether there is one preferred reform for the initiative process that you would support. I have a favorite. My favorite is to end ballot box budgeting or diminish it in some way. And my fantasy is an initiative title that says, “An Act to Diminish the Budgets for Roads and Schools and Spend it Instead on X.” It would be interesting to hear from the panel if there is a reform that they would like to see what they would like to propose or endorse.

Jeff Flint: The only one that doesn’t bother me a whole lot is — which we dealt with because our firm campaigns all over the country, but it tends to be a little bit more on the western half of the country than elsewhere — is in Nevada where measures have to pass twice. So, a measure passes and then two years later it’s on the ballot again, so there’s that, “Did we really mean to do that?” out of maybe the haste of what generated it the first time. You could probably talk me into the Nevada process of initiatives having to pass twice just so the vote — now that I say that, that sounds pretty darn self-serving for a guy who makes money running initiatives. Twice to be exact.

Jon Fleischman: I was going to say that.

Jeff Flint: That’s pretty funny. I wasn’t even thinking that. I was trying to be semi-academic there. I wasn’t trying to be greedy. All right, never mind, I’m going to shut up now that I realize how that could be misconstrued.

Matt McCubbins: If I could think of some sort of process and probably this is more tongue in cheek, I would say that if the voters overturned a law passed by a stupid legislator that maybe that legislator loses his seat in the process.

Shaun Bowler: I don’t actually know because I end up spending so much time defending what is that I don’t think about much of the change. So, I’d like to think about that a bit more, about what the reforms are and what they’re intended to do because at the end of it … Oh, this isn’t working?

I want to know what the problem is, before I start going for solutions. I see this all the time on my campus among academics, it is this sort of “Shoot, fire, aim.” We’ve got solutions, but I don’t know what the problem is. I really am unsure what the problem is about the initiative process. For example, everyone blames Proposition 13. Proposition 13 is probably one of those that would pass again, because when it first passed, people were paying higher taxes at the same time as the state was running this giant surplus. It was just this predatory state kind of idea. Some of these things, I don’t know if they are problems, so I don’t know if they require a fixup; as opposed to some other things that might require fixups.

I’m trying to be balanced, since I spent a lot of time banging on about how awful the Democrats are. The Republican party, for example, is basically putting itself out of business in the state. It’s becoming more and more extreme, more and more conservative, and gradually dwindling. It seems to me that the state has a problem if it becomes a one party system, rather than a competitive two party system. I think that’s a problem that we might want to think about, rather than disappointment in the initiative process. Yes, in principle there are reforms, but I don’t know what the problems are with it right now.

Matt McCubbins: Right, that’s where I began my talk, talking about the legal process school. The joke I didn’t finish with was, whenever you ask legislators what problems are, they’ll point to “Oh, this particular law needs to be changed” or “We’re doing too much.” If you ask the people what’s going on, and it’s the legislature’s passing corrupt laws. What’s the answer to that? Pass more laws. Legislators and the people always think that what we need to do is pass more laws, pass more policies. I’ve heard several people mention it, we talk about people not being engaged in the electoral process. We’re not engaged at all in the implementation process, so we pass these policies off, and then don’t watch whether to see that they’re implemented or not. We have a paper in the Southern California Law Review of two years ago now, with a dual path initiative process, which integrates some of these ideas from Nevada and a few other places on changing it, but it’s far too complicated to talk about here in a brief sentence.

I don’t think the answer is to pass more laws and try to fix things, as Shaun said. We often don’t think about what the target is before we try to go and do things.

Audience Question (man): Just speaking for myself, not suggesting that there is a problem, except maybe the one that I perceive; and also speaking as someone who may be of a conservative bent and a great admirer of the notion of original intent, I think we would all agree that the original intent of the initiative process was sort of a demand-side argument. That there is a public that is so angry and frustrated with the legislature, that out of the general public will emerges a demand, a cry for change, in which the initiative process was designed to facilitate that process. Now, about three years ago, I sat in Rob Reiner’s office for an hour and a half, interviewing him for about an hour and half about his Proposition 10, which was an idea that he divined in his office with a group of other people, got together with a group of other funders and decided on his own, based on his infatuation with a brain theory about child development, to impose a tax on cigarette smokers on the grounds that it would provide a fund of money for early childhood development, and hence we have Proposition 10.

There was no great hue and cry out in the general public for this. We have an initiative by someone who became enamored with the need for stem cell research, and funded, almost on his own, a ballot measure. By the way, this suggests that the initiative process is not necessarily a great defense against size of government. It might be in the case of taxes, but I’m not sure how the initiative process necessarily defends anyone against intrusions of a very angry public.

In any case, do our practitioners have any suggestion, or do they think there’s anything wrong at all with the notion of increasing numbers of well-heeled individuals and groups who simply decide on their own; not because there’s a great demand or a great anger in the public; to simply press? I realize it provides a lot of business for our consultants, but if they can remove themselves from that particular personal interest, how do they feel about this?

Jeff Flint: I think part of the challenge is, who is the great determiner of when a wealthy person or group of wealthy people put something on the ballot that is in their personal interest, like T. Boone Pickens putting that whole wind power deal on the ballot. The voters saw through that! They saw that he had bought up all the real estate that would benefit from it, but at the same time there are other measures. Clearly, it was all of the businesses that benefited from building a high speed rail that completely funded the measure to build a high speed rail! It wasn’t a group of altruistic people saying “Oh, let’s take one percent of the people and put them on these quick trains!” The problem is, at the end of the day, the people have to be depended on to sort through those issues, and it brings us right back to all the inherent challenges that we’ve talked about, because it’s a political process. In order to have an educated electorate, it means that people have to A) be checked into the game, and be willing to be educated, and when they do that, then it’s how do you get them to write information; how do you get them to sort through all of the advocacy mail.

It’s a very complicated process. I would be the first one to say that -- like term limits itself, which I’m not a fan of, but supported because I was very angry about what happened in Sacramento, I’m not a fan of the initiative process. I just believe that the initiative process is a better process, a lot of the times, than what takes place in Sacramento. And so, I think we’re all going to sit here and talk about the way that the system is flawed, it can be used, it can be abused, absolutely. The reality, though, is that any time you have a government by the people, for the people, people are flawed.

You do the best that you can, and you try to have a system that works as good as it can, and you hope that the people try to do the right thing, but is it subject to abuse? Sure it is. How much do you really embrace the spirit of America, if you start to say “Well, let’s come up with a way to keep some ideas from being ballot measures, but have other ideas be ballot measures?” If you say you can’t give money to a ballot measure unless you have, what, at least 10,000 people that want to write a check?

It becomes a very difficult process, and I don’t think there’s any answers. The greatest answer of all would be to somehow fix the problem with the state legislature so that they were more responsive to what the people want, so that the people would see less ballot measures, or if they did, they would reject them because they would say “You know what? I’m comfortable with what’s going on in Sacramento, so I don’t feel the need to pass this by the people.” But that’s a long road to get there.

— Transcription by CastingWords