Discussing State Finance

Panel Tackles How to Fix California's Deficit

October 20, 2009

By Valerie Orleans

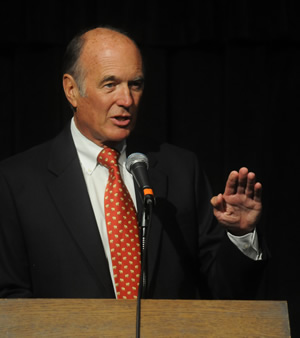

Dick Ackerman

With a $24 billion deficit, the state of California has some serious problems. But how to fix them?

That’s the challenge that a panel of experts discussed recently at Cal State Fullerton. The panelists: Former state Sen. Dick Ackerman; Max Neiman, senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California; Rod Kiewiet, professor of political science at Caltech; and Robert Turnage, assistant vice chancellor for budget for the California State University system.

The speakers agreed that there are many reasons why it is so difficult to resolve budget issues in California — term limits, the two-thirds vote and the state’s initiative process are among them.

“The way the system used to work is at the beginning of each year, the governor would propose a budget and then the budget committee in each house, Assembly and Senate, would have three or four months to hold hearings,” Ackerman explained. “When the ‘May revise’ came out, they’d have updated numbers."

Max Neiman

At that point, six people (three from each house) would gather and iron out their differences; each house approves the budget, and then, the governor signed it or vetoed it.

Today, the governor and a group of legislative leaders (the assembly speaker, assembly minority leader, senate president pro tempore and senate minority leader), dubbed “The Big Five,” develop the budget.

“To boil it down to five people making a decision for 36 million people in the state of California … is a very poor way of developing a budget,” Ackerman said. “There are other extenuating factors that contribute to the state’s budget woes: a large number of initiatives that lock in legislators.”

The areas that the initiatives support, such as education, after-school programs and transportation, are all worthwhile, he added. But that only leaves legislators with a discretionary amount of leeway when considering budget matters.

Rod Kiewiet

“Policymaking is philosophically complicated because people come to the table with very sincere and very genuine differences about values and priorities,” said Neiman. “It’s often difficult just to establish common ground.”

Neiman pointed out that the state’s size also could create problems. For instance, he said, for the amount of money the country spends on education, only a small percentage gets into the classroom; America's borders require vast investments of resources and spending; and there are issues with flood control and water quality.

“The recurrent budget crises have made a shambles of local budgeting, both at the county and the city level,” Neiman said. “This has created an intense adversarial relationship between the cities, counties and the state. It had really resulted, to some extent, in turning local governments into part of the interest group system. They have really seen themselves now as just simply one more player in this massive interest group system that operates in Sacramento.”

Kiewiet pointed out that all is not dire. In fact, California has 20 of the top 100 fastest-growing companies in the country, he said.

Robert Turnage

“The state doesn’t live in isolation,” he said. “We compete, or we should be competing, very fiercely with the other states for employees, companies and things like that. When you make public policy, there are effects and consequences that are very important, but are not necessarily things you envision or foresee at the time you implement a public policy.”

Turnage has spent more than 25 years working with the state Legislature.

“As I look at what’s happened since I first started working in the state capital in 1982, it’s really pretty breathtaking,” he said. “And if you look at just the last year, this last budget cycle has really exposed kind of a soft underbelly of California state government. It is absolutely the worst budget situation that I ever witnessed since 1982. And, everyone else I know who is a veteran of the capital feels the same way.

“It’s worse not just because the state has had a recession,” he added. “There’s been a very sharp recession, and that has certainly contributed to it. But, the rest of the country’s had a recession, too. And California’s bond ratings have fallen to 50th of the 50 states. The absolute worst rating, just a couple of notches above junk. … There are lots of other signs of a systematic breakdown in the process. So the recession has helped to expose problems, but these problems that have led to this current budget crisis have been many years in the making.”

Turnage points out that besides Arkansas and Rhode Island, California is the only state with a two-thirds majority requirement to pass a budget.

There is increased partisanship, and district lines are drawn to protect incumbents, he said. As a result, legislators are less responsive to the people and more responsive to their base of support. Term limits have led to a lack of experience.

“So, even the leadership, the speaker of the Assembly, may be somebody who just arrived in the Legislature a year or two ago,” Turnage said. “It also becomes structurally more difficult for the leaders to actually lead their respective caucuses. There is less ability, there's less stability, less ability to demand loyalty on important questions. And sometimes, you do have to have leadership, exercise leadership and get the members of your caucus to take votes that are difficult. They may be difficult, but that’s what is necessary for the state.”

On Audio

The panel discussion is available on audio (MP3, 63MB).

Discussion Transcription

The following is the transcription:

Sarah Hill: We have some fun participants today. This is going to be a fun panel. Now depending on the latest figures, this year, the state of California has faced a budget deficit on the order of $24 billion. It might have changed recently, but that was one number I could find. And, in order to handle this deficit, the state legislature has had to make some difficult decisions. One of the reasons why I think this is so interesting is the Cal State community has definitely been affected quite personally by some of the budget problems this year. And so, this is something that certainly has affected all of us.

As difficult as this fiscal year is though, I think our big concern is what lies ahead. What will future fiscal years look like? Is the budget process going to keep giving us budgets like this? And I think that's a question that I'm excited to hear some answers to today. I'm looking forward to what our panelists will have to say.

I'll give some brief introductions here. And, the plan here is that after the introductions, our panelists will each have 10 minutes to give you their take on California's budget process. And then, after that we'll open it up to questions from the audience, so please think about questions you might have for our panel. And also, if you all have any questions for each other that would be wonderful too.

So introductions. Our first panelist is Sen. Dick Ackerman. He has 25 years of experience in elected office as a California State Senator, State Assemblyman, and city councilman. He's served as vice chair of the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee, and spent four years as the Senate Republican leader. He was one of the legislative leaders charged with consulting with California's governor on key infrastructure and budget issues.

And today, Senator Ackerman continues to practice business and corporate law. Actually one of the most interesting pieces of information I just found out about him was that he was a math major when he was in college, and I was too. That always horrifies my students. But, I'm wondering if that gives you extra insight into the budget process? So, I'm curious to hear about that.

And then, next, we have Max Neiman. And Dr. Neiman is now a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. He was on the political science faculty at the University of California Riverside for many years, and his research interests are in local government and local economic development. And he told me he's been watching what's been going on in Sacramento very carefully, so I'm sure he has some good insights for us.

Rod Kiewiet is our third panelist. And Rod is a Professor of political science at Cal Tech. He was my graduate school adviser, so I'm especially excited to have him here today. And his research interests are quite diverse, but he studies American politics, public policy, and California politics.

In particular, Professor Kiewiet has looked at how Proposition 13 has affected public school finance in California. And I know he's done some data research and is excited to get to share with you all today.

And then, our fourth panelist is Robert Turnage, who is the assistant vice chancellor of budget for the California State University System. And in this capacity, he serves as the system's representative on budget matters in the state capital, and also administers allocations of state support funds and student fee revenues to the systems' 23 campuses.

He has 18 years of experience with the Legislative Analyst's Office, where he learned about the workings of California's legislature and how it affects higher education. And given how the Cal State system has been affected by this crisis, I know we're very interested to hear his take on things.

So with that I'm going to turn it over to the panelists for about 10 minutes each to hear their take on California's budget process.

Dick Ackerman: Thank you. I'm glad to be here and welcome to you all. I thought the title was a little interesting: "How the California Budget Works." Actually the title should be "How the California Budget Does Not Work," because I think it's been pretty clear in the last year and year and a half that it is not working.

I thought I'd tell you a little bit about how the process is supposed to work, and then tell you some of the constraints on why it doesn't work that way. And then, I'll talk just briefly about a proposed constitutional convention to try and change the whole thing.

The way the system is supposed to work and it used to work this way probably up until maybe 15 years ago or so at the beginning of each year, the governor proposes a budget. It's his responsibility to propose a budget.

So he puts out a budget, and in each House, the Assembly and the Senate has a budget committee, and they are supposed to study that budget and make recommendations. They have hearings for maybe three or four months. And they never make any definitive things, so they always wait until May, which is when the May revision of the budget comes out.

So they have hearings for maybe three or four months. They go through a lot of preliminary things. They take testimony on all the various issues in education, prisons, and so on and they make some preliminary decisions. Then the May revision comes out in May, which is a good time for the May revision.

And the reason that's important is that's when you get the best numbers coming out of the LAO's office, the Treasurer's office, and all the updated numbers on income and expenses.

And then, at that time, the budget committee reconvenes, and they're supposed to fine tune all the decisions they made based on real numbers; because now they've got better numbers coming out of May. And assuming both Houses agree on a certain budget which they never do because they're always a little different then they form a conference committee.

So you start out with 120 people in both Houses, the budget committee and the Assembly probably has about 20 or 25 people in it. The budget committee and the Senate probably have about 10 or 12.

So you go through all that, and you through the May revision. And then, you have a conference committee, which generally has six people on it three from each House and they're supposed to iron out the differences between the two budgets, between the Assembly and the Senate.

They come out with a product and then it goes to one House. It has to be approved by both Houses, the Senate and the Assembly by a two thirds vote. And generally, in the old days, that would go through, and then it has to go to the governor. The governor signs or vetoes it.

Generally, the governor's office is involved in the entire process, so if it goes through and there are no major problems, the governor will probably sign it. The governor in California has a blue pencil. He has a line item veto, so he or she can knock out whatever they want, and then the budget is done.

And that worked, like I said, for a long, long time, up until...and I'm not sure exactly what it was. I've only been there for 13 years, and I know it hasn't been working well for 13, but prior to that it may have worked for a little bit.

The problem lately is there have been so many contentious issues, that a lot of these issues are made by the Big Five. You may or may not have heard of the Big Five. The Big Five is the governor and the legislative leaders: the Speaker of the Assembly, the Republican leader from the Assembly, (the pro tempore) the Democrat from the Senate, and the Republican leader from the Senate, which I was.

So those five people basically are called upon to make a lot decisions. I've got to tell a joke about when I was first elected Senate Republican leader. There was a thing in the paper saying that I was now part of the Big Five. So one of my friends called up and he's not real political and he says, "What number are you?" And I said, "It's not number one, I can tell you that."

So fast forward to where we are, and I think these last 12 18 months have been a pretty good example. The budget committees have been meeting on and off in both the Assembly and the Senate, but basically they haven't been coming up with any conclusions.

And practically all the decisions that have been made have been made by the Big Five, which are basically the legislative leaders. And I can tell you that's a very bad way to run a budget.

One-hundred-twenty people get elected to go up there representing their constituency. They're supposed to have hearings. They're supposed to review all these things. And to boil it down to five people making a decision for 36 million people in the state of California when those five people are not listening to testimony, they're not getting input from all of you, from all the various interest groups throughout the state of California is a very poor way of running a budget.

And you can see the result of that, which we've had for the last year; we've had a lot of chaos and we've had a lot of problems.

The other reason we've had these problems is the income has gone down. California income has gone up and up every year I've been there, except this last year. When there's a lot of money, it's always easier to do things, because basically you're spending new money.

When you have less money, which we've had in the last two years, then you have to cut things. You have to raise taxes, or you have to make cuts. The Republicans generally do not like to raise taxes, and the Democrats do not like to cut programs, so you have a problem.

But this year, it particularly showed that the failure of the current budget system was very glaring. Like I said, you can't have five people in the state of California when you've got a whole bunch of people up there elected trying to make decisions, and that's what they did.

A couple of other things that have made it difficult to budget in California is our initiative process. We have a number of initiatives, which are on the books, which lock in and basically tell the legislature how you're going to spend money. The biggest one is Prop 98.

Prop 98 guarantees about 40 percent to 45 percent of each of the budget year, each year, in all new money to go through education. Basically most of it is K 12, but it's actually K 14. It includes the community colleges.

That is the biggest section of the budget; that is locked in. When I first got elected, I actually read Prop 98, and that was a big mistake. I would not urge anybody to read it. I read it, and it was totally confusing. I'll just give you a little example about how convoluted it is, it was, and it still is.

On years when you have a very high income in the state, there's various thresholds in 98. Depending on how much income comes in, it tells you what the funding is going to be for education. Historically, in the last few years when we've had years of very high income it's funded education at the lowest rate, which doesn't make much sense. The years when you've had very low income it funds education at a very high rate, which it doesn't make any sense at all anyway, that's locked in.

There's a number of other propositions, all very well intended. One of them guarantees a certain amount for public safety, for fire and police, which is all very good. One guarantees money for transportation, for roads, which is again very good. It locks in a certain amount of the income.

Governor Schwarzenegger got his start on Proposition I think it was 49 which guarantees money for after school programs, which is also very good. It's basically sort of a constitutional guarantee, which locks in money for a program. They're all good, but it may or may not be a high priority, especially when you have low income coming into the state, but taking all of these various initiatives into consideration.

The legislature is actually sort of locked in. They have a discretionary amount of leeway they have on deciding what to do with dollars without suspending the Constitution or without suspending some of these propositions, but it's very, very difficult.

One of the things that is being considered as one of the items for a Constitutional Convention is to revise this thing, to take a look at some of those initiatives. The problem is anytime you look at any Prop 13, which talks about property tax, or Prop 98, they're sort of a third rail to everybody. It just lights everybody up, and it's probably very difficult to do even though they should probably all be looked at.

Another problem with the budget is that all budgets in California require two thirds vote. Most states require only majority vote. There's only maybe two or three states that require a super majority, and California is one of them.

I can argue both ways on that, but I think probably the better good government angle is to have a majority of vote, because then when you have a bad budget you can really blame whoever parties in power to do it. Right now if you have a two thirds vote, both Republicans and Democrats have to vote for it, so you can't say "They did it" when you have both parties voting for it.

One of the proposals out there is to have a majority vote budget, but have it two thirds for taxes, which I think is very appropriate. As long as you have some protection for people so the majority party in power just can't raise taxes, that's probably a good idea.

The other problem we have in California is prisons. Right now we have a big prison problem. We used to spend a small amount of money on prison, now we're spending a very large amount. We spend probably twice as much as any other major state on prisons, the cost for a prisoner, which is way out of whack.

You may have read there is a judge in San Francisco who now is taking over the medical portion of the prison. He's ordered the state to spend about $8 or $10 billion dollars to build new hospitals for prisoners, because he thinks we're not taking care of them well enough, which I think is totally ludicrous. We have various people that are pulling each way to try and do something.

The budget process I think needs substantial rework. I think everybody has realized that. Just a little side note, we've passed about two or three budgets this last year. The one before this last one actually had a big tax increase, which they got a few republicans to vote for that. A number of those republicans are now being recalled, so I don't think you're going to see anymore tax increases.

But even in spite of that, after raising taxes $12 billion dollars about six months ago, we're still going to have about an $8 or $10 billion dollar deficit going into January. We're probably going to get through the end of the year without running out of cash, but you're going to see the governor probably call in another special session to do something in the budget before December.

I can guarantee it as soon as January hits, we are going to be in a deficit mode again, and you're going to see the same arguments coming out.

One of the issues just philosophically, is whether or not we have a spending problem in California or whether we have an income problem in California. I'll just leave you with one statistic. In 1993, which was 25 years ago, the state budget general fund was $38 billion dollars. In 2008, which was one of our largest years, there was $103 billion dollars. So it went from $38 to $103 in 25 years.

I just look at the short time I was in the legislature; I was there from '95 to last year. In 1995 the general fund budget was about $45 billion, and it went up to $108 or $103. So in my opinion, we do not have an income problem in California. We're generating plenty of money coming in, because we are one of the highest tax states with personal income tax, corporate tax, sales tax, etc., but we just spend too much.

I had my staff do a little analysis while I was still there, just rolling back the budget maybe five years and locking it at some number, and I forget what it was. I said, "Pick a number, $50 billion or $60 billion."

I said, "Just take that number and increase it by population growth, case load growth and CPI, and see where we should be." If we would have done that back then, we would have about an $8 or $10 billion dollar surplus now. We would not be spending the $85 per year that we're spending right now.

So, in my mind there's no question that we have a spending problem in California. We've tried various spending caps. That's always a popular thing to try and put a spending cap in, but I've learned in my short 10 year in the legislature that whatever spending cap you have, somebody is going to try and figure out a way to get around it.

So when I run into those things that sound good, it's not necessarily one that is going to work. I do think we do have plenty of income coming into California. Even though our total income now is down, it will show back up. We always have peaks and valleys in income.

California is still a very spontaneous and very aggressive, and very successful business state. So our income will go up, but we definitely have to control spending. I teach a class at Berkley part time. I'm a teacher, I forget about that too.

I had Willie Brown as one of my speakers. Willie's been up there for a long time. He basically admitted that he and the democrats just spent too much money. It's OK when you have money to spend it, but when that income goes down; you have to have a way to decrease it.

I'll just close with one story with my favorite budget advisor, President Bill Clinton. A number of years ago I met him at an airport, and I was with Speaker Nunez, who was then the Speaker of the California Assembly, and Nunez was in love with Clinton.

We were having a budget crisis back then, and Clinton said, "What's the problem?" He's from Arkansas, they never have any problems. He said, "What's the problem?" and he said, "Well, our income has gone down."

He said, "In Arkansas they have an automatic formula. If income goes up past a certain amount, I don't know whether it's 4% or 5%, a certain amount automatically goes to a reserve, a certain amount goes to education, a certain amount goes someplace else."

"Similarly when the income goes down, there's automatic cuts in place." They all say, "We're going to cutback here. We'll use the reserve for a little bit. We're going to cut education. We're going to cut welfare. We're going to do these things," and it made immediate sense. Actually, we tried to do this a couple of times in California, but we were unsuccessful.

So I kept bugging the Speaker. I said, "Did you hear what your President just said?" He said, "No, he just wanted a photo op." He wanted to have a picture with him. But I think some kind of formula like that is useful. Hopefully, if there is a Constitutional Convention and they do talk about their budget, that's one of the things you're going to do, so you avoid having these arguments, because income is going to go up, whatever state you're in.

California is probably the worst or best example. Your income is going to go up sometimes, it's going to go down sometimes, and to have a formula in place ahead of time would make it much better. Other than that, the California budget is in great shape.

Thank you.

Max Neiman: Well, I sat through the earlier panel and professors were accused of being long winded and weight backs. So I'm going to try and keep it as short as I possibly can, but who knows what that will ultimately turn out to be? If I quit with the preliminaries, maybe we'll have some more time here. So, this is a tough topic; talking about policy making with respect to budgets is tough. Part of it of course is technically a very complicated subject, but it's also philosophically complicated with people who come to the table with very sincere and very genuine differences about values and priorities.

So, it's often difficult to just try to establish a common ground where you're even speaking the same language. For example, Senator Ackerman pointed out that is it a spending problem or is it a revenue problem?

Well, I think it's partly both a typical wimpy professor response, but it's also more than just a spending and revenue problem. It's also a priorities issue. For example, we do spend a lot of money for prison and corrections. We spend more per prisoner than any other state in the United States. But yet, we have a court order that's basically taken over the medical program in our prisons.

And we spend a lot for students in California, but very small percentage of it gets into the classroom. So, we also have an infrastructure in California. It's very serious. We spend a lot of money on infrastructure, but no one would deny that our port facilities and particularly the gateways coming out of the West Coast and going eastward require vast investments of resources and spending.

Our infrastructure in the Central Valley particularly around the Delta region, and the problem that we have with flood control and with water quality, which could affect of course, the entire state; very expensive propositions to deal with. So there are important expenditure issues and revenue issues and it's a hard one to sort out.

And I do appreciate, by the way, I have no particular investment in Senator Ackerman, we surely miss people like Senator Ackerman in the legislature, right now. Too bad for term limits, I think.

So in any case, it is a very complicated topic. So let me just talk about the fact that a good deal of discussion is wrapped around, as we referred to them earlier this morning, and I thought, for me, somewhat offensively by a former colleague of mine as the weasels, a pack of weasels or a plague of weasels who run the state legislature.

And that the budget processes is basically taken over by a bunch of partisan ideologues on both sides. And it is to some extent that way. It seems that way, particularly at the end of the year when we're frantically trying to beat the bond ratings and trying to put together a package that would be acceptable in this particular climate.

But the fact is that most of the year, if you actually follow, if you do what I don't, kind of a junkie on this. So if I watched Cal Channel, which is a station that streams legislative hearings during the year and you watched legislators at work and you realize that for a lot of stuff that goes on in the Capitol building, but which doesn't get reported, there is a lot of good, cordial bipartisan stuff going on in the legislature.

So what goes on at the budget stage, it seems to bring out the worst and causes so much difficulty for the state of California. So much of the darkness, and the skepticism and the frustration we feel about politicians. And the process in California is wrapped around the budget process. And of course, there are many good reasons for us to be California centric.

I love the state, I think it's the centre of the universe just like most of us do, but the fact is that lot of what's going on in California isn't unique to California, at least in the present time.

It's true that we are recidivist with respect to certain problems like getting a budget done on time. But the fact is that there are many, many states right now, in roughly the same fix we're in, and in some cases, considerably worse fixes than we're in. So, I think it's important to understand that some of this is at least contemporarily, part of the overall problem that the country faces with the meltdown in the economy.

But there are some things that contribute various streams of things people talk about. But unlike a cake, where you explain a cake by saying, well, it's got a little bit of this and a little bit of that, and it was baked in a certain amount of time at the following temperature, and this is what we got.

And if I'm doing it, it's not going to be very pretty, but you can surely have interpreted. With the problem that we have, it's a combination of a bunch of different streaming factors that come together to produce this mess that people are concerned about. And it's hard to figure out which one contributes the most or which one is the silver bullet, if there is anyone.

But term limits to some extent is often talked about. I can't go through all of the individual arguments for each one of these things, but term limits, partisan redistricting is an important consideration. Your two thirds requirement both to approve budgets and to raise taxes, the increasing social shorting of the State of California.

I mean, to some extent the partisanship in the Legislature reflects what's happening among the political parties on the ground. People in fact have become more divided politically, and you can see it on the political maps of California.

It's no longer quite as much a north south divide and increasingly a kind of coastal inland divide, but to some extent the divisions in the Legislature do reflect the divisions within the State. It is a complicated state and there are important divisions, and some of that does get reflected in the Legislature.

There are possible size effects that exaggerate. By size effects I mean as a minority party, in this case the Republican Party, has gotten smaller relative to the majority party. It has become more important for the party to maintain cohesion. It can't afford to have defectors or too many of them when it comes to making some of these decisions.

And I don't think there's anybody here either who would deny that if Democrats were in the same position that the Republicans are vis √ vis their numbers in the Legislature, that they too wouldn't be using the two thirds requirement in pretty much the same way the Republicans are for a different agenda perhaps. So it is in some sense a structural issue here.

And of course, as it becomes difficult to forge a winning coalition around a budget question, the role of interest groups becomes really, really important and intense.

And anybody who will visit the Legislature during these frantic weeks and days when the budget is past due, and begins to see the lobbying activity and the organized interest from labor unions to corporate interests to non government organizations, you name it, roaming in the halls and sitting across the street with their Blackberries and communicating and texting, it's very intense.

And of course, the cost of winning becomes higher and higher as the difficulty of achieving that win increases. So all of these things are contributions.

Some of the things I think we ought to be concerned about, that we ought to broaden the discussion. Of course, I think Professor Kiewiet is going to talk about budget volatility and revenue volatility, am I right? So I'm not going to touch that.

But clearly one thing that's important to me is the impact that the revenue process, and I hesitate to say this because I'm not an unvarnished critic of Proposition 13, I have mixed feelings about Proposition 13, but certainly one effect has been to undermine local government in California.

Not just institutionally, but the recurrent budget crises have made a shambles of local budgeting both at the county and the city level, and has created an adversarial relationship, an intense adversarial relationship between the cities, counties and the State.

It had really resulted of course to some extent in turning local governments into, I suppose they always have been part of the interest group system, but have really seen themselves now as just simply one more player in this massive interest group system that operates in Sacramento.

And increasingly, budget and revenue and planning at the local level has become more and more difficult as a result of the State's inability to manage its fiscal affairs in these kinds of times.

There are budgetary processes that we could talk about that could improve things incrementally: greater transparency in the budget process, changing procedures, things that could be done without constitutional conventions or initiatives. But there are some reforms that I'll talk about.

I just will sort of by way of passing endorse the notion of broadening the tax base. Probably a compromise would have to result so that the overall tax bill might be comparable but at the same time broaden the tax base much more broadly than it is, particularly with respect to consumption activity and services.

Some reforms are already on the agenda and might have some positive effects. We'll have to see how redistricting works out with the new citizens commissions that will come into place in 2012.

There is on the ballot the top two vote getter proposals, which has some promising potential for reducing the partisanship of those people ultimately run for office. It basically assists them whereby the top two vote getters in the primaries, regardless of party, go in for it.

So if your two top vote getters are both Democrats or both Republicans and go for the general election if none gets a 50% vote. And what happens in that case is that presumably you have people running on a much broader platform.

Earlier today one of the Conservative or more Republican members of the panel stated that one of the things he didn't like about the initiative process and, I believe, the two thirds rules and the super majority requirements is that it basically doesn't provide a real incentive or push to oblige the Republican Party to build a statewide political base.

It can rule as a minority party by virtue of making demands at the budget process stage and it would otherwise not have. So he feels, and I do too, this tends to reinforce a much more narrow base for the Republican Party.

Finally, I would like a good hard portion of the revenue banks go back to local governments and provide for local governments the option. In other words, leave the default be the two thirds requirement for special taxes, so that everybody at the local level, all counties and cities, would basically start with the two thirds requirement, but be permitted to choose to go to a simple majority without having a statewide vote for it.

I think as a conservative it seems very strange that you would support a system, which has, so badly undermined local government rule and has put every local community at the mercy of the statewide electorate. I think each local community should have genuine authority to make policy. I think it would be important for any number of reasons, but I think I've gone a bit past my 10 minutes, so I'll leave it at that.

Rod Kiewiet: I need about 40 copies there, so. One of the nicknames of economics, that you may or may not have heard about, is "The dismal science." That's due to the fact that a major figure in early economics was Thomas Malthus, who figured out if present trends continue that the human race would starve to death.

But really, most of the time economics is not the dismal science it's politics that's the dismal science. What we talk about in politics is generally, what's wrong, and what people are unhappy with, and what's broken, and what's wasteful; and inefficient, and fraudulent, and things like that. I'm in favor of doing that, don't get me wrong, but I think sometimes that tone sort of becomes too pervasive.

I should tell you upfront I really am very optimistic about the future of California. I think the main reason is I've been at the game of higher education teaching at the college and university level for over 30 years. So, I had your parents as students. Trust me, compared to your parents, the students of today are much better informed, much more hard working, and have a lot better attitude.

When you're in colleges and universities on a day to day basis it's just almost impossible to be pessimistic about the future of California. There are a lot of good things going on. The statistic I read lately was that nearly 20 of the top 100 fastest growing companies in the country are in California. I think eventually we're going to be OK.

I do want to, in this brief period of time I have to spend with you, kind of give you, I think, a broad overview of the dollar and cents nature of the budget problems that we face today as a state. I want to try to broaden the focus a little bit, to get beyond just Sacramento.

California does not exist in isolation either today, in a point in time, or geographically in this huge country. We compete, or we should be competing, very fiercely with the other states for employees, and companies, and things like that. Some of what I want to do is try to figure out how we stand now compared to earlier years and how we stand compared to other states.

So, I prepared a handout. Most people in academia do PowerPoint presentations now. I like the paper technology quite a bit. You can take it home with you when you're done. We don't all have to look at the same slide at the same time. You can go back and forth. I find these marvelous advantages of paper.

Apparently, the data indicate that paper will outlast almost all of our other digital media. A five year old CD, maybe you can read it made you can't, but this should last a long time.

At any rate, I've compiled some data for you. Most of it related to this infamous Proposition 13, which was put in place before the students in this room were born and was seen as a watershed revolutionary event in the history of California. In some respects that's true. Far less true, I think, than most people have made it out to be, at least that's what I've argued in several papers and a book.

I do want to show you, first of all, just to show you what the impact of Prop 13 was. Basically what you can see if you look at the California column between 1973 and 1974 the reliance of state and local governments in California upon property taxes shifted very dramatically away from property taxes.

Not surprising that was the whole point of the thing was to cut property taxes and bring them under control and to move into other sources.

I've just compared income taxes as one point in comparison. I think the thing that you want to see is that that was going on, not to the same extent, but to a similar extent, in all of the other states put together. All of the other states in the union, over this time period, had been moving away from reliance on property taxes and more towards income taxes, sales taxes, charges and fees.

There's a lot of reasons for that. If you do public opinion polls, people really hate property taxes! It turns out perennially to be the tax that people hate. In a way, this just tells you the legislators are paying attention; is the way I interpret it.

A theme of this morning's session, which I guess I'm going to have to reproach, is a lot of times when you make public policy there are effects and consequences that are very important, but are not necessarily things you envision or foresee at time you implement a public policy.

One of the things that's happened and on the second page I have some data from LA County is that within the things that you impose property taxes on, at least in Los Angeles County. I'm pretty confident this holds for the rest of the state.

Prop 13 has resulted in a very significant shift away from the taxation of commercial and industrial property and toward the taxation of single family residential property. The houses your moms and dad own, or the bank owns, or some combination thereof.

As you can see, that this shift has been fairly dramatic. That's mainly because the value of single family residential property in this state had been going up much more rapidly than commercial industrial property.

I'm not an expert on this, but I think the warehouses and retail buildings did not get caught up in this sort of out of control sub prime mortgage induced housing boom that we've experienced over the last decade. But it does mean that when you think about where property taxes come from, it's increasingly from houses and increasingly not from factories and warehouses.

One of the other consequences of Prop 13, it was noted at the time, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Rose Bird, who was famous for a lot of other reasons. You can Google her either now or later. Very much opposed Prop 13 because it treated similar pieces of property very differently. And that is in fact the case.

If a house has not been sold since 1975, it's still taxed at pretty much the 1975 level, plus two percent. So, my neighbor across the street, Joanne, who has lived in that house since the late 60s, they're fairly similar houses. But her property tax bill is probably about 10 percent of my tax bill, because I bought more recently, and she has had that house since 1975.

And so one of the things that is a sort of weird residual of Prop 13, is about one out of seven houses out there have not changed hands, or have not been reassessed, importantly, since 1975. In the earlier years the rate at which, they called the base year, 1975 base year parcels, they disappeared rapidly in the early years. But in the last few years, it's really moved at a very glacial pace.

There are a number of ways I guess you can pass the Prop. 13 thing on to your kids now. Is that right? And so there are ways to keep the Prop. 13 protection going into the future. I'm not crazy about that. It is a problem that over the next few decades will be eradicated completely. But it still bothers me that my neighbor pays 10 percent of the property taxes that I do.

The next thing, and this is sort of the big set of data in the last page, is what I've tracked to the best of my ability, especially in the later years when you're getting numbers from a lot of different sources and trying to reconcile them.

But I think they're really accurate until about 2006, 2007, and then a little squishier. But I feel pretty comfortable with them as a whole. It's basically the revenue raised by the various revenue sources in the State of California since 1991.

And I've looked at property taxes, general sales taxes, income taxes, corporate income taxes. And C and M is what the budget people call charges and miscellaneous. That's of relevance to you guys.

That's where tuition goes, and all the other things that the state government charges fees directly for services for. That is not available, at least in any way that I could find after 2006. From what I can gather, they've raised your tuition, for example. You picked up on that.

That's held pretty steady. But there are a couple of trends here that I think are interesting, and a couple that I worry about. One is: despite the weirdness of Prop 13 at the individual house level, where one house can be taxed 10 times more heavily than another, even though they're the same house, it has a very, very nice macro fiscal property of just kind of going up all the time.

And there's a lot of reasons for that. Every time a house would sell, it would be reassessed at the new market value. And that would sometimes be a manifold increase in the taxation collected from that house. There is a two percent increase every year. And so it has since its inception, actually as a revenue generator, been a very nice, steady, ongoing, increasing source of revenue.

It wasn't until this last fiscal year, and in July, that it actually went down, by less than one percent. Now, it's sort of like a huge aircraft carrier. And because it's slowed down, that's actually disturbing. Because I think it will continue to slow down.

In L.A. County, for example, about 25 percent of all the houses in the county were granted peremptorily by Rick Auerbach. I congratulate him actually, the tax assessor, a decline in value. So they will, because the value of their house is going down below the Prop 13 level, they will get a lower tax bill.

That process, I believe, will continue apace for the next few years. And so even though the property tax revenue has been a nice, ongoing, ever growing source of revenue, my belief is now that it actually has declined, that the inertial elements of that tax will continue to drive it down slowly over the next three or four years.

So the bad news there is probably, the property tax revenue stream is not going to be what you'd like it to be, even as California economy hopefully recovers.

When you look at general sales tax, they also had an increase very steadily. But something I noticed that's disturbing, if you think of it as a revenue source, is it topped out around 2005, 2006. Economy was doing good then. I think what we're seeing is the impact of the Internet.

I think unfortunately, now in recent years, the sales tax rates have reached levels of 8, nine percent, that kind of level where it's noticeable; it's a big tax now. Think about buying a new car that cost $28, 000, and if you cross the border, you could save $2, 800. What do you think, worth the trip? And so not strictly legal.

But other things like tax on tobacco, on cigarettes, it's extremely high. The figures I read are roughly 35 to 40 percent of all the cigarettes sold in California come from out of state, where the tax is very much lower.

So this is the thing, Californian exists in a country of 49 other states, which generally can yield important tax savings, either through the Internet or by driving there that not all did sales tax revenue decline rapidly during the economic slowdown of last year. So I fear it's not going to come back in any important way, for these reasons.

Income taxes also fell off a cliff into the 2008, 2009. They had declined in the previous Internet bubble recession of the 2001, 2002 level. But it was a lot worse this time. There's a lot of reasons for that.

People don't make as much money, hold them only is the main reason. But they're not realizing capital gains; they're in fact detecting capital losses. The income tax compared to the property tax far, far more volatile tax, in terms of the revenue that it produces. I think it will come back as the economy comes back. I'm not quite as worried about that as I am with the sales tax.

Corporate income taxes; I don't know anything about it, I'll be honest. But they've done good. I mean, corporations continue to pay taxes, I don't know why, but there you go. And again, I don't have the data of the charges and miscellaneous, but I believe those will continue to be used heavily, and in fact more so in the next three or four years.

And I'm sorry to tell you that. I know you've got a giant tuition increase this year, but it's very difficult for me to think you won't get that for another three or four years in a row. So that is additional for college students?

On the other hand, the good news; did people tell you this? If you get a college degree, you make about $24, 000 a year more every year, you live and if you don't, still an excellent return. And it is again, the California tuition levels are not all that high compared to a lot of other states.

So, Unfortunately, I think that we'll be moving up to catch up with the rest of the country. So I think... what people, this is just speculative back of the envelope projections on the basis of numbers that I see. And so I really welcome any comments or alternative theories from people looking at this data. So, thank you very much.

Robert Turnage: Glad to be here today. I'm Robert Turnage with the Chancellor's Office. And I've been working in or with the Legislature since 1982 on budget matters, wearing different hats at different times. Right now I work for the state university system. And I'm going to speak much faster than I normally do. My father was from Mississippi, so I grew up patterning myself to speak in very deliberate ways.

But I'm going to try and move it fast, because I know 10 minutes is a very concentrated time, and the subject is huge. As I look at what's happened since I first started working in the state capital in 1982, it's really pretty breathtaking. And if you look at just the last year, this last budget cycle has really exposed kind of a soft underbelly of California state government. It is absolutely the worst budget situation that I ever witnessed since '82. And everyone else I know who is a veteran of the capital feels the same way.

And it's worse not just because the state has had a recession. There's been a very sharp recession, and that has certainly contributed to it. But the rest of the country's had a recession too. And still California's bond ratings have fallen to 50th of the 50 states. The absolute worst rating, just a couple of notches above junk.

Now that didn't happen just because there was a recession in this state. And there are lots of other signs of a systematic breakdown in the process. So the recession has helped to expose problems, but these problems that have led to this current budget crisis have been many years in the making.

The other speakers on the panel have spoken about some of them, this buildup over the last 30 years or so of different propositions, starting with Proposition 13. But each proposition, in one way or another, hemming in policy makers in Sacramento, and making it more difficult for them to make choices on behalf of the people.

There are some structural problems. One that has been referred to is the two thirds vote requirement. California is the only state in the country that has a two thirds vote requirement, both for passing the state budget, and for passing taxes.

And there are only two other states that have a two thirds requirement for passing a budget. And those states are Arkansas and Rhode Island. Very small, homogeneous states that bear no resemblance to California in terms of diversity, and the complexity of the society and the issues that they are confronted with.

Now, 25 years ago the two thirds requirement didn't seem to present too much of a hurdle. But what has also been happening, one of the trends that has been distressing, has been an increased partisanship among office holders. Not just in the Legislature, but in political office generally. And you can see this trend happening nationally as well. But it has happened with a vengeance in California.

One of the structural things that has contributed to that partisanship has been the way that district lines are drawn. They are drawn in order to protect incumbents. And so just about everyone runs now in what is called a safe district.

The election that's held in November is not really a competitive election. It's been rigged by the way the lines have been drawn, so that you have an overwhelming number of people either Democrat or Republican. And the November election is a cakewalk.

What is competitive are the primary races in the Republican and the Democratic primaries in each district. That's where the real fighting happens.

So what that has led to over time has been a legislature that is less responsive to the people as a whole and more responsive to the extreme base of whichever party they're a member of. And that has not been conducive towards trying to fashion compromises in the Capital, to say the least.

Another structural problem, I think, has been term limits. Term limits was something adopted by the voters back in 1990, I think with good intentions.

But the result has I think been detrimental because now what goes on is you have members of the legislature who, number one, are not around long enough to develop any real policy expertise in the different areas. They may get to chair the budget committee for two years but then they're on to something else.

They also don't have time to develop relationships with each other. Everybody now is instead of thinking long term is thinking two or four years down the road to what's the next office to run for because I know I'm going to be term limited out of here pretty soon.

And in the Assembly, what terms limits has done as opposed to the Senate where you have at least some reservoir of experience, is you have no one who has any experience. And so, even the leadership, the speaker of the speaker of the Assembly may be somebody who just arrived in the legislature a year or two ago.

It also becomes structurally more difficult for the leaders to actually lead their respective caucuses. It becomes much more a question of herding cats. There is less ability, there's less stability, less ability to demand loyalty on important questions.

And sometimes you do have to have leadership, exercise leadership and get the members of your caucus to take votes that are difficult. They may be difficult, but they're what's necessary for the State.

Now, the thing that I mentioned about the way the district lines are drawn, at least that we have some hope for on the horizon. In the 2012 elections, thanks to a proposition that was passed a couple of years ago, that process is going to change and we'll have an independent commission drawing the lines.

Hopefully, what is going to happen from that is you're going to develop a political center again in the legislature where you'll have people who are willing to depart from party orthodoxy and actually reach compromises. So that's one hopeful change.

If we look at other trends, here's a trend that I think matters for everybody sitting in this room, and that is if you look back at the state budget 25 years ago, now one of the propositions that got passed in the 1990s was three strikes. That has contributed towards ballooning costs in the prison system.

Well 25 years ago the State of California spent less money on the state prisons than it spent on the California State University system a lot less. Only 60 percent as much money was spent on the prisons as on CSU.

Twenty-five years later the amount of money that the State spends on prisons is greater than the combined amount that the State spends on the CSU, the University of California and the community colleges. So, I would argue that over the last couple decades what California has been doing is it's been investing in incarceration rather than education.

Now, nobody did that deliberately. This is one of those things that's like the water temperature keeps going up and up and up, and pretty soon whatever is in the pot has been killed by boiling water.

There's just been this sort of tyranny of small decisions that has happened year after year. It's not like members of the Legislature consciously set out, "Oh, this is something we want to do. We want to start spending more money on prisons than on universities." It happened by degrees. But now we have gotten ourselves caught in this bind.

And what has happened of course in the last cycle, all of these problems sort of converging, and then this great recession overlaying it, has resulted in very tough choices that have had to have been made in the last year.

And including state funding for CSU dropping from two years ago it was at $3 billion. In two years it has slid to $1.6 billion. And even if you throw in this one time life vest that got tossed to us by Congress in the form of federal stimulus money, even if you add that back in, we're still at $2.3 billion.

So we've fallen from $3 billion down to $2.3 billion. That's $700 million. And most of it, the decisions ended up happening in late July this year. So the Chancellor and the Board of Trustees were basically faced with an absolute emergency and no fun choices at all.

But there were no options. It's not like the state university doesn't have the ability to say, "Oh, I'm now confronted with a $700 million deficit. Well, I'll just go out and borrow that." We are not legally able to operate that way, nor would it be a prudent thing to do fiscally.

But what's happening to the universities is also happening to other public programs as well. So it is a difficult situation that we're in. I won't take up any more time trying to sort of forecast what I see for next year.

I'm sure there will be some questions about that but I think we are in for a prolonged period of difficulty. And ultimately I think for California to kind of right itself is going to require a number of major structural reforms. The problems are not just going to disappear once the recession is over. We have some serious work to do as a state.

Anyway, pleased to be here, and pleased to be part of this panel today. Thanks.

Sarah Hill: Well thank you to each of our panelists. And now I would like to go ahead and open it up to questions. OK, Professor Jarvis is going to have the mic, and please go ahead.

Prof. Jarvis: Well, first of all, I want to throw in a plug for the Public Policy Institute.

Woman 1: There we go. Is it on?

Man 1: Yeah, that's good.

Man 2: You've got the best ears.

Prof. Jarvis: Can you hear me now?

Man 2: Very good.

Prof. Jarvis: At the Public Policy Institute, it's a great resource. You can Google it to find a lot of my information there. Also, there is the California Budget Project, CBP, which is very helpful in finding information. Again, it's comments and probably questions for input. But according to the "Wall Street Journal", California is 18th as far as taxing states. It is not one of the highest taxed states in the country. We hear this an awful lot. So go back and question some of this stuff.

Sarah Hill: Yes. I did want to ask each of our panelists, when you answer, please make sure you're speaking into this microphone.

Man 3: Can you hear me? Is this on? It's on? It depends whether you're looking at rates or revenue, which I alluded to a little bit. Yeah, we don't take in that much revenue. I mean we're 18th, 20th I've heard, 22nd.

Prof. Jarvis: Yeah. And this is, I say, according to the "Wall Street Journal". Man 3: On the other hand, if you look at tax rates, we have perhaps one of the very high marginal income tax rates and an extraordinarily high sales tax rates. And that's where you are, and the problem is you're in competition with other states. And as those rates go up, they don't necessarily produce more revenue. And that is why I'm afraid we'll find out, going forward.

Sarah Hill: Yeah. We are a state for high income. However, you get the tax rate and the effective rate, which is with all the write offs which people actually pay.

But what I wanted to do is just zero in on Prop 13, because after the passage of Prop 13, that is when California really started getting all the budget difficulties. Prior to Prop 13 was the inclusion of the two thirds requirement to raise taxes. That happened as part of Prop 13.

Also it's ineffective government or ineffectual government. At that time, Jerry Brown was governor, and everyone knew we needed property tax reform, and the legislators didn't act. The governor didn't leave, and therefore you got prop 13 in vogue there.

At that time, it was a good time. California's gone bust and boom historically: the oil wells, the defense industry, the airline industry, the dot com, up and down. And so when Prop 13 happened, the state took over the property tax and said, "Don't worry local government, the state will come in and help you.

And there was a surplus and political parties or political individuals said, "This is the people's money, we don't need a rainy day fund; let's have a tax refund." So that was the car tax, which funded a lot of local government, was decreased.

And when we had Gray Davis trying to restore the car tax again, you know what happened. So it's complicated, but if you look back historically, it was back in '78 when Prop 13 passed. Sorry, I took so long.

Dick Ackerman: Just wanted to comment on the tax rate. And I think you hit it. About 10 percent, less than 10 percent of the people in California paid 90 percent of the personal income tax. That's why you see Tiger Woods doesn't live in California, the Williams sisters don't live here, even though she has a little less money now.

We did an analysis when Arnold got elected, what he pays in state income tax. And generally, the state income tax is pretty high, and the threshold is high. If he moved out of the state of California, it would take 12, 000 regular income earners to pay the same amount that he pays in state income tax alone. So you can see why superrich people do not live in California, and that hurts our economy because they're not here buying things.

So our tax rate, we may not be the highest. But if you look at each category; income tax, corporate income tax, sales tax, which was mentioned, very high sales tax and including property tax. We are very unwelcome state to be there. And if you look at businesses, businesses are not relocating into California.

We used to be the fifth largest economy in the world, we're now the eighth, and there's a reason for that. Businesses are not locating here; they are locating to others states which have cheaper tax rates.

Sarah Hill: Are there other responses from our panelists? Yeah.

Max Neiman: I'm pretty eclectic about this. To me, the fact that California is 18th, 19th, 20th, 22nd on some ranking doesn't necessarily justify that it shouldn't be the 28th or 30th or 35th. There's no logical relationship between where the state is. And of course, as a factual consideration, we certainly want to know if California has a greater tax burden generally speaking, for the average household. And in that sense, it's probably not. The state of California is probably the eighth largest economy in the world because Taiwan has become very important, India has become very important a number of other countries have advanced over time. It doesn't necessarily reflect a slide on the part of California. We tried to look at this question of businesses moving in and out. And we, at the Public Policy Institute of California, have now put together a data set.

— Transcription by CastingWords