Heart and Soul

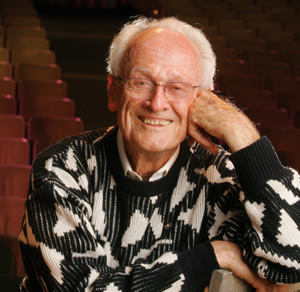

Emeritus professor, donor and Rotarian Jim Young leads Performing Arts fundraising with heart and soul.

Reprinted from the Spring 2005 issue of Titan Magazine

By John Kroll

Jim Young

The word begins with 'd,' means "ardent attachment to a person or cause," and seems particularly applicable to the life and career of Jim Young, founding chair of Cal State Fullerton's Theatre and Dance Department. The word is "devotion."

It now sounds slightly archaic, suggesting a knight on an unachievable quest or in love with an unattainable lady. And because Jim Young, at age 84, can mark more than 60 years of marriage to the same woman and can look forward to the opening in January of the theater bearing his name in the new Performing Arts Center, it is clear that in his case, the lady has been attained and the quest achieved. His life is an example of devotion fulfilled.

Young is devoted to theater both as a craft and as a way to enlighten those who experience it. When founding President William Langsdorf hired him from Pepperdine in 1960 to establish a theater department at Fullerton, he urged Young to offer courses, such as history of the theater, because the college lacked stage facilities. Young told him, "No. The foundation of the program at Cal State Fullerton will be living theater."

That view led him to mount plays on the fifth floor of the first campus building, in an improvised space known as "Theater in the Sky," using costumes from thrift shops or residents' attics and flood lights borrowed from local merchants. Students pulled curtains along guy wires. "Once you establish your conventions, the audience will accept them," Young told his troupe.

Among the initial shows was "A Midsummer Night's Dream." "I was determined to do at least one classical show each year, a tradition that's continuing now" [in fact, the 2004-05 season's production of Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale was selected for regional competition in the American College Theater Festival by invitation from the Kenedy Center] "and that pleases me greatly," Young says.

Mimicking the traveling companies of old England, Young's budding actors filled campus gardeners' carts with props and wheeled them to store parking lots, where they performed one-act plays for initially astonished but receptive community members. The department's stature grew to the extent that the state legislature authorized a performing arts center as the campus' second building–erected even before a library.

Young believes theater enlightens those who experience it on either side of the footlights. Jack Schlatter, who studied with Young at Pepperdine and later became a CSUF drama teacher, recalls, "Every show started out with young actors and actresses coming together as a cast. By the time the final curtain came down, we had become a family. Dr. Young had many methods of bringing this miracle about, but the most important was the meeting before each show [opened]. People shared what the play had taught them and what they had learned from each other. What an influence that wise, humble, kind, committed gentleman has had on so many lives."

Audiences sometimes receive enlightenment by taking offense at a play. His production of "The Merchant of Venice" drew threats from people who saw it as anti-Semitic. The late Arthur Miller's "The Crucible" was attacked because it took issue with the tactics of Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Young says, "There are no seat belts in any theater–and no requirement that you attend. When you are offended, then you learn where you stand."

The most heated confrontation came in the late 1960s with a student production of a now little-remembered play, "The Beard," a two-character confrontation between Billy the Kid and Jean Harlow that included simulated sex. Despite restrictions on who could attend, the production led to a state Senate investigation. Interrogating Young, reactionary Orange County Sen. John Schmitz asked him, "Do you believe this is an important play?" Young replied, "It wasn't, sir, until you made it so." Although then-Gov. Ronald Reagan urged that Young and a colleague be fired, the administration stood up for them, on the principle that the Legislature could not come into a university and tell faculty members how to run their classes.

Recalling the incident, P. June Pollak, then chair of the Faculty Council, notes, "Though he was the primary focus of the attack, Jim Young never gave up or gave in. He's a good man in a fight."

Looking back on the controversies, Young says, "The point is not whether I like or dislike a show. I dislike the people in "Macbeth." But just as medical students study the body, we in theater need to study people's emotions and motivations."

When Young says "we in theater," he takes an inclusive view. He has always rejected the ideas that theater is a specialized discipline and that theater people are a breed apart. Instead, he links theater to the rest of learning and the rest of life. "I never encouraged students to major in theater if they planned to make it a career. I would urge them to major in philosophy, psychology or world religion, so they could apply what they learned there in theater work, whether in performing or costume design. But if I found students who planned to teach or go into law in the ministry, I would encourage them to major in theater because all of that is performance."

In the same spirit, he refused to build a theater program isolated from the rest of the curriculum. He convinced the Physics Department to offer a course in acoustics and lighting that would demonstrate the impact of light on costume fabrics. He encouraged formation of a course on theater history in the History Department because, he says, theater mirrors the culture. And as associate vice president of the academic programs, a position he assumed in 1972, he initiated a general education requirement for at least one participatory course, such as theater, dance or debate, to give students a physical experience in one of these areas– a requirement still in effect.

Young retired in 1991, leaving a legacy of memorable productions and an approach to theater and to education as a whole, in both senses of the phrase. But his devotion to Cal State Fullerton and the larger community continued.

Active at the university's Ruby Gerontology Center, he moderates the "Poetry for Pleasure" class for its Continuing Learning Experience program and sometimes performs. Last spring, says CLE's Kirt Spradlin, "Jim's stunning, animated presentation of 'Casey at the Bat,' totally from memory, mesmerized the entire audience and inspired the volunteer ushers for the Titan baseball team."

He also contributes his own poetry to the group. According to class member Lorna Funk, it encompasses "his childhood on the frontier southwest of Roswell, New Mexico, his strong-willed grandmother, his dark memories of serving during World War II in the South Pacific, his undergraduate years at Northwestern University [where he majored in business, not theater], and his pride at founding the Fullerton department."

"He is still a wonderfully inspiring teacher and a riveting performer," Funk says, "helping us find to new talent within ourselves and to use pauses, intonation and eye contact to communicate with our audiences."

An active Rotarian, he performs worldwide a short play he devised about the Rotary Club founder and donates his honorariums to the organization to promote understanding of people around the globe. In recent months he performed in India and Manila, among other locations.

In addition to serving as president of the emeriti, his gifts to the university take a tangible form. He co-founded the "It's Our University" (IOU) campaign, an annual program of faculty-staff-emeriti-funded donations, which has raised $3.2 million in 12 years. He has been instrumental in raising money for the new Performing Arts Center, including major gifts, and has himself donated large sums to the complex. His most recent contribution funds the Dorothy Rea Young Green Room, honoring his wife of 61 years–a love story that inspires many who know them.

Darlene Warner-Zivich, once a student in Young's oral interpretation class and now associate development director for CSUF's College of the Arts, recalls, "After class he read my selection of Shakespeare to me to demonstrate the feeling he wanted. He looked right at me and spoke so eloquently that I was sure he was in love with me. Minutes later he told me that as he spoke, he was visualizing his wife's face. The moment was so touching that I never forgot it."

She is one of the many–alumni and others– who have been inspired by Jim Young's devotion.

The university has responded. It has named him an honorary alumnus–the one faculty member to receive that recognition.