|

American Studies Professor Publishes New Look at One of America's Favorite Writers

BY VALERIE ORLEANS

From Dateline (September 2, 2004)

|

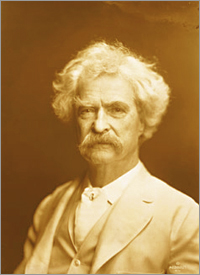

| Mark Twain |

|

|

A widely celebrated author battling against

the ravages of age and depression. Two disloyal employees. A daughter

sent to a sanitarium and forced to stay away from her beloved father.

It has all the makings of a good detective story,

doesn’t it?

Karen Lystra, professor of American studies, thought

so too.

Her research led to the spring publication of her

book “Dangerous Intimacy: The Untold Story of Mark Twain’s

Final Years,” in which Lystra probes some of the theories

of Twain’s later years and focuses more attention on his youngest

daughter, Jean Clemens.

“There is this image of Mark Twain, in his

later years, as depressed, cheerless and melancholy,” Lystra

says. “And while Twain was depressed by his wife’s illness

and death in 1904, I discovered that there was more to the story

than most people commonly believed. I began to see Jean Clemens

as the key to the story of Twain’s later life.”

In most biographies, Jean, who suffered from epilepsy,

is portrayed as wild, violent and out-of-control. In fact, one biographer

refers to her as “the daughter Twain wanted to forget.”

In Lystra’s research, however, the evidence shows that Jean

was not the daughter Twain ever forgot, or wanted to, and he developed

a deep kinship with her before he died.

There is no question that Jean did have epilepsy

and spent several years in virtual exile from her father –

living in a sanitarium. However, the reasons for her stay are suspect.

It was alleged by Twain’s secretary, Isabel Lyon, that Jean

attacked and attempted to kill the family housekeeper. Yet based

on her research, Lystra concluded that Jean was a gentle, kindhearted

soul.

“Jean was particularly compassionate to both

people and animals – and devoted to her father,” says

Lystra. “However, at that time, epilepsy frightened people.

It wouldn’t have been difficult to convince people that epilepsy

included violent episodes, although today we know this isn’t

the case. And in Jean’s case, there was absolutely no evidence

to suggest unmanageable anger, homicidal aggression or any form

of mental illness.”

So how did this theory of Jean’s violent behavior

take root?

Lyon, one of Twain’s most trusted confidants,

may have had an ulterior purpose in removing Jean from his life.

Many scholars have speculated that Lyon was in love with her employer,

and removing his daughters from his life may have been directly

related to securing and enhancing her own position.

In another odd twist, it has come to light that Lyon

and Ralph Ashcroft, Twain’s business manager, were no doubt

embezzling money from the noted author. Eventually, Lyon and Ashcroft

ended up marrying and later divorced, creating further speculation.

In one of Twain’s last unpublished manuscripts,

he himself alluded to the collusion of his two formerly trusted

confidantes. He charged that Lyon sought to exile Jean from his

house and confessed that as a widowed father, he had failed –

perhaps to the point of betrayal – to confront his daughter’s

condition and to live up to his parental authority. He furiously

repudiated any characterization of his daughter as “crazy.”

And what of Lyon and Ashcroft? They maintained that

Twain was delusional and losing his grip on reality as he slid into

depression. In fact, in most biographies, Twain’s accounts

are generally discounted in favor of his secretary’s.

“What is key is the state of Twain’s

mind in his 70s,” says Lystra. “Whose account do you

believe?” While conducting her research, Lystra poured over

the records of Twain’s finances. She found a much-contested

power of attorney drafted by Ashcroft. There also were letters,

private contracts, an independent audit and a memorandum written

by Ashcroft in defense of Lyon and himself.

Lystra contrasted these against Jean’s diaries

that were frank, open and guileless.

“Her diaries were important because, unlike

her father, she wasn’t writing for a reader, and unlike Lyon

and Ashcroft, she wasn’t writing to vindicate herself,”

Lystra explains. “She discusses what it is like for her to

live with epilepsy and provides a rare view of life inside a sanitarium

in the early 20th century.”

Lystra also read accounts by Twain’s other

daughter, Clara, as well as other household members – trying

to ferret out the true story of what really happened as Twain grew

older.

“This has all the drama of the human experience

– the search for love, estrangement between parent and child,

betrayal by those you trust, coping with age and loneliness,”

says Lystra. “It certainly puts a more human face on Twain,

challenging the myth of depression, melancholy and despair that

surrounded his later years.

“Identity is a problem at any age. It’s

a struggle to know who you are and it’s never really over,”

she concludes. “I hope this book will give readers space to

find their own way in the story of Mark Twain and come to their

own conclusions.”

« back to Research

|