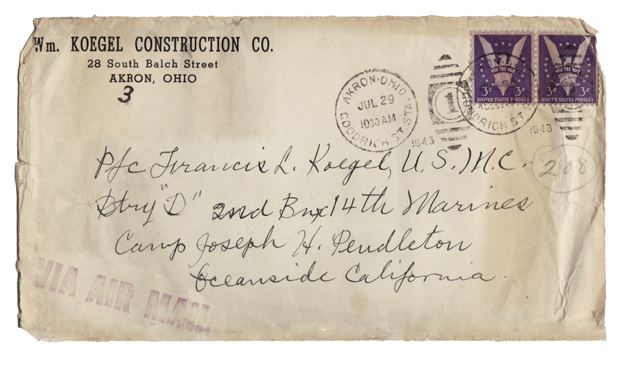

Caption: "A letter my grandfather wrote to my father during the war provides a clue to the importance of German culture and literature to both of them. He urged his son always to be proud of his German heritage while upholding the honor of America, and to serve as a model soldier. To inspire his son, this carpenter from Akron, Ohio, who had little formal education, quoted a poem by Goethe in German and gave his own beautiful translation into English. This letter is an important link to my German ancestry. . . ." — John Koegel. Photo courtesy of the author.

Caption: "A letter my grandfather wrote to my father during the war provides a clue to the importance of German culture and literature to both of them. He urged his son always to be proud of his German heritage while upholding the honor of America, and to serve as a model soldier. To inspire his son, this carpenter from Akron, Ohio, who had little formal education, quoted a poem by Goethe in German and gave his own beautiful translation into English. This letter is an important link to my German ancestry. . . ." — John Koegel. Photo courtesy of the author.

Faculty Book Excerpt

Author’s Research Inspired by Family Ties

Ancestry Leads to Study of German American Theater

Editor's Note: In this excerpt from the preface, music professor John Koegel describes the circumstances that awakened his interest in German culture and inspired the curiosity that led him to write "Music in German Immigrant Theater: New York City, 1840-1940."

This book began as the result of a chance remark in 1984 by Stephen Ledbetter about a musical with the evocative title Der Pawnbroker von der East Side by then almost entirely unknown theater composer Adolf Philipp. The newspaper clippings and Philipp's song I found at the New York Public Library whetted my curiosity. The more I dug the more I discovered about Philipp and the German American theater, and the more I realized that this vanished tradition had been a significant force in the American theater.

I also discovered that almost all of the published research on the German immigrant stage in America ignored the musical aspect. After several years of research, I decided to embark on a long-term project to uncover what I could about Philipp's immigrant-themed musicals, and to place these in the context of the German immigrant community in New York and elsewhere in the United States. But it only gradually occurred to me that I needed to write the history of the German immigrant theater in New York, with a focus on its musical component while at the same time taking into account the entire theatrical repertory.

The longer I researched the more I realized the vastness of the topic and daunting nature of recovering, translating, and interpreting the surviving documents.

Caption: The German-language Thalia Theater on the Bowery in lower Manhattan in the later 19th century, the area indicated in the map below.

Caption: The German-language Thalia Theater on the Bowery in lower Manhattan in the later 19th century, the area indicated in the map below.

My research has taken me to many libraries and archives throughout the country in search of information about performers, composers, playwrights, repertory, and audiences, and has led me to consult an incredibly wide range of materials. It has been a wonderful journey, one that I have enjoyed thoroughly. If I had known in 1984 how much work and time it would take to complete this book, I wonder if I would have continued with the project! I am very glad I preserved.

Besides my desire to reconstruct and understand this theatrical and musical history, another important motivation for this book has been to acknowledge and honor my own ethnic heritage as a third- (and fourth-, and sixth-) generation German American. My many German immigrant ancestors—the Koegels, Kleins, Knapps, and Lingenfelsers, and my other more distant German relatives—embraced the patterns of acculturation and assimilation so typically experienced by German Americans and other ethnic groups. But unlike many other groups, German Americans generally have not maintained a strong sense of ethnic self-identification, at least in California where I grew up. This loss of cultural memory is a sad thing.

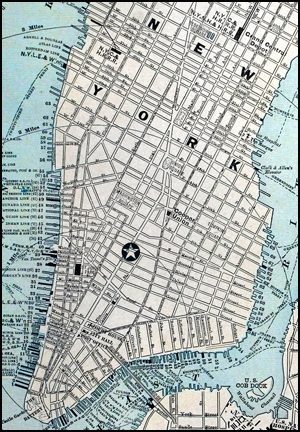

Caption: A street map of New York City at the turn of the 20th century. The star marks the location of the German-language Thalia Theater.

Caption: A street map of New York City at the turn of the 20th century. The star marks the location of the German-language Thalia Theater.

So, this book also represents my attempt to understand the ethnic heritage that was not emphasized in my own family. My father, Francis Koegel, was a second-generation German American who was taught some German by this father, and belonged to his university's Deutscher Verein (German Club). My grandfather, Wilhelm Kögel (William Koegel) emigrated to America at the beginning of the twentieth century from the village of Daxlanden near Karlsruhe in Baden. Even though my father felt a connection to German culture, he did not share this with his children. Perhaps the experience of being a German American soldier during World War II, when our country was at war with Nazi Germany, shaped his perception of his ethnicity and German heritage. I cannot know, however, since he never spoke of it. But a letter my grandfather wrote to my father during the war provides a clue to the importance of German culture and literature to both of them. He urged his son always to be proud of his German heritage while upholding the honor of America, and to serve as a model soldier. To inspire his son, this carpenter from Akron, Ohio, who had little formal education, quoted a poem by Goethe in German and gave his own beautiful translation into English. This letter is an important link to my German ancestry, and over the many years I have worked on this book I have often thought of it. I only wish I could show this book to my father and my mother, Anne Marie Koegel, and the grandparents I never met, and ask them about the ethnic heritage about which I knew little before undertaking this project.

Reprinted with the permission of the author from "Music in German Immigrant Theater: New York City, 1840–1940," University of Rochester Press, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by John Koegel.

November 28, 2011