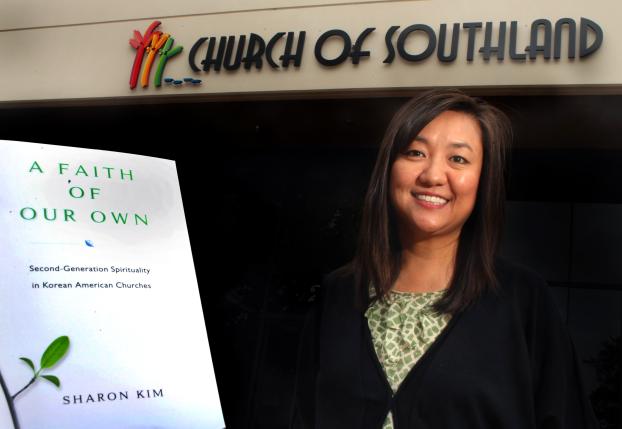

Caption: Sharon S. Kim and her book, “A Faith of Our Own,” in front of one of dozens of churches, where she conducted research. Photo by Karen TapiaDownload Photo

Caption: Sharon S. Kim and her book, “A Faith of Our Own,” in front of one of dozens of churches, where she conducted research. Photo by Karen TapiaDownload Photo

Second Generation Faith

Korean Americans Create New Kind of Church Experience

LIKE THEIR ANCESTORS before them, they fall to their knees, screaming, crying, fists pounding the floor, calling on God to answer their prayers.

The emotionally charged prayer, tongsongkido in Korean, may be the only traditional custom practiced in today’s Korean American Christian churches. Founded by second-generation Koreans, the churches are not their parents’ houses of worship.

“These new churches are trying to be more multiracial, more communal,” said Sharon S. Kim, assistant professor of sociology, who recently authored “A Faith of Our Own,” a Rutgers University Press book based on a decade of research on Korean American Christianity.

“Rather than assimilating into mainstream American evangelical churches or inheriting the churches of their immigrant parents, second-generation [those born in the United States to immigrant parents] pastors are creating their own hybrid space — new autonomous churches,” Kim said. “Services in these churches are in English and the members are young, mostly the children of immigrants who came to America after 1965.”

Through her research, Kim found that the churches, including her husband’s Garden Christian Fellowship in Chatsworth, started emerging, after the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

“The church is the central cultural institution in the Korean community, and it served as the representative of Korean victims of the riots,” said Kim, who joined Cal State Fullerton’s faculty in 2005. “But immigrant church leaders, who spoke little or no English, turned to the English-speaking second generation. That shift in leadership marked a coming of age, a transition of power.”

According to the U.S. Census, there are about 250,000 Korean Americans (nearly 74 percent born abroad) living in Los Angeles and Orange counties. Their churches number in the thousands.

In 2008, there were 56 second-generation churches in Los Angeles and Orange counties, said Kim, who studied 22 of them for her book.

“Today, there are about 70 second-generation churches,” she said. “When these churches first started, there was resistance from the older generation who wanted to remain unified and traditional.”

In her book, Kim describes the struggle. An excerpt:

“Because Korean immigrants see themselves as outsiders in American mainstream society, the church plays an important role in gratifying their need for inclusion, significance, social status, respect and power. This reality, according to a second-generation Korean American pastor, allows the church to become the fertile ground for ‘flesh, fights and fury.’

“The second generation, as they entered young adulthood during the mid- to late ’80s, began to vocalize discontent over the immigrant churches, which they felt catered primarily to the needs of their parents’ generation. During this period, tensions and schisms between the first and second generation began to surface and multiply. The most acute tensions revolved around three issues. First, younger pastors began to view the immigrant churches as dysfunctional and hypocritical religious institutions that were modeling a negative expression of Christian spirituality for second-generation Korean Americans. Second, there were continual clashes between the generations over issues involving cultural differences in the styles and philosophies of church leadership. Finally, the younger generation felt that they were being treated as second-class citizens in the church because their needs were consistently unmet and viewed as inferior to those of the first generation.”

Scholars who study Korean immigration and religion said Kim’s research is a significant contribution.

“I think Dr. Kim has done some of the best work on second-generation Korean American churches,” said David K. Yoo, director and professor of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center and Department. “Her analysis takes into account the varied nature of this phenomenon and has broader implications for the religious experiences of other post-1965 immigrant groups. It is an important study."

October 12, 2010