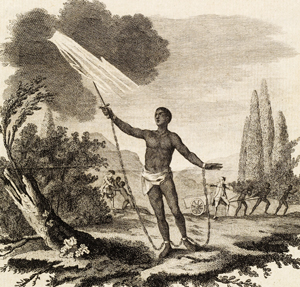

Caption: This is an illustration from an 1838 issue of American Anti-Slavery Almanac, which illustrated a passage from Charles Ball’s “Slavery in the United States” (New York, 1837) that describes Ball’s encounter with the slave Paul. Paul had “suffered so much in slavery, that he chose to encounter the hardships and perils of a runaway.” The illustration was reproduced in Terri L. Snyder's award-winning article on slavery and suicide.

Caption: This is an illustration from an 1838 issue of American Anti-Slavery Almanac, which illustrated a passage from Charles Ball’s “Slavery in the United States” (New York, 1837) that describes Ball’s encounter with the slave Paul. Paul had “suffered so much in slavery, that he chose to encounter the hardships and perils of a runaway.” The illustration was reproduced in Terri L. Snyder's award-winning article on slavery and suicide.

Suicidal Tendencies

Professor Awarded Prize for Research on Slavery and Suicide

IN 1803, A GROUP OF AFRICAN SLAVES being shipped up the coast of Georgia staged a revolt, taking control of the vessel. The crew fled and the ship ran aground. Resisting recapture, the slaves “took to the marsh” and drowned themselves.

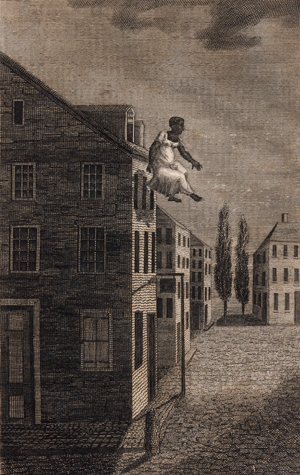

Caption: Also reproduced with permission from The Huntington Library, this illustration, Jesse Torrey, appeared in Snyder’s article. It depicts an unnamed slave woman, who on Dec. 19, 1815, jumped out of the garret window of a three-story brick house and survived.

Caption: Also reproduced with permission from The Huntington Library, this illustration, Jesse Torrey, appeared in Snyder’s article. It depicts an unnamed slave woman, who on Dec. 19, 1815, jumped out of the garret window of a three-story brick house and survived.

The collective suicide gave rise to local folklore in which the slaves were remembered as “flying Africans,” that is, slaves who “possessed the power to literally fly from enslavement,” Terri L. Snyder wrote in her award-winning Journal of American History article, “Suicide, Slavery and Memory in North America.”

Snyder, professor of American studies, recently won the Western Association of Women Historians’ Judith Lee Ridge Prize for her work. The prize recognizes the best article in the field of history authored by a WAWH member.

“Terri Snyder’s beautifully written article explores the horrifying narratives of suicide among slaves,” said Marie Francois, associate professor of history at Cal State Channel Islands and Ridge Prize chairwoman.

Francois said the prize judges noted that Snyder’s article “employs the concept of slave suicide ecology — emotional, psychological and material conditions — that fostered suicide to examine power relations such as kidnapping, forced migration and rape, as well as other sources of power that include religious beliefs and gendered social constructions. Especially insightful is her use of ‘flying African’ folklore in illustrating the power of cultural memory for slaves, ex-slaves and abolitionists.”

Snyder’s article is part of a bigger book project that was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship in 2007.

“I am honored to be the recipient of the Ridge Prize and the NEH Fellowship, both of which reflect positively on CSUF,” Snyder said. “While professors are most often associated with the dissemination of knowledge in the classroom, we also create knowledge. CSUF is a teaching-intensive university, and the support provided by external and internal fellowships and grants was invaluable to me in this regard.”

Snyder’s article opens with the story of the 1803 group suicide and traces how it was transformed over the decades from a story of tragedy into a tale of strength and resistance.

“In the 1930s, ex-slaves in the region recounted their oral histories of both the 1803 collective suicide and the flying African folklore and linked them to their own experiences of slavery,” Snyder said. “The link between the suicide, its oral history and the folklore it generated, reflects the power of cultural memory to keep alive past tragedy and reshape its meanings for future generations.”

The article also analyzes “The Dying Negro,” a poem, published in 1773, that focuses on a suicidal slave.

“The poem assumes the persona of the slave who believes that he has secured his freedom, but kills himself when he learns that he is to be sold back into slavery,” Snyder noted. “The poem was widely reprinted in American newspapers and amplified the contradictions of the chattel principle — that is, were slaves commodities or persons?”

Caption: This illustration, also reproduced by permission from The Huntington Library in Snyder's article, illustrates a poem, “The Dying Negro,” published in 1773.

Caption: This illustration, also reproduced by permission from The Huntington Library in Snyder's article, illustrates a poem, “The Dying Negro,” published in 1773.

The first stanza of the poem:

Arm’d _with thy sad last gift — the pow’r to die,

Thy shafts, stern fortune, now I can defy;

Thy dreadful mercy points at length the shore,

Where all is peace, and men are slaves no more;

This weapon, ev’n in chains, the brave can wield,

And vanquish’d, quit triumphantly the field:

Beneath such wrongs let pallid Christians live,

Such they can perpetrate, and may forgive.

Snyder said the poem is an example of a cultural form that had the power to influence political debates over the legitimacy of slavery.

The following is an excerpt from the last page of her article, which is available for download through the Pollak Library website:

The flying African stories lie at the crossroads of memory and history.… The stories assert the power of culture to maintain community in the face of its forcible dislocation.… Flying African folklore allows for the possibility of escaping slavery through the supernatural power of refusal, rather than through self-destructive violence. Like both the African- and North American-born slaves who contemplated or chose self-inflicted death, flying Africans also made a choice. Collective memory conferred upon them the power to fly — to escape slavery and to return home. Ex-slave memories and folklore perform the cultural work of remaking the history of the self, the family and the community within slavery, ultimately transforming the crossroads of despair, suicide and separation into an intersection of power, transcendence and reunion.

Snyder, who joined Cal State Fullerton’s faculty in 1989, is finishing her second book, “The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in North America, 1630-1830.” It encompasses specific acts of self-destruction by slaves and the cultural meanings and political purposes assigned to those acts, as well as traces changing attitudes toward suicide and slavery in early America, she said.

While suicide has always been considered a serious act, “our understandings of suicide – what causes it and how to deter it — have changed tremendously over time,” Snyder said. “Today, for instance, the suicide rate for returning Gulf and Iraq War veterans has spiked upward and constitutes an urgent problem for which physicians and psychologists rightly seek solutions and explanations.”

“In contemporary America, we typically link suicide to mental distress, extend sympathy toward victims of suicide, and support hotlines and other measures to prevent self-destruction. Yet, these are fairly recent responses to suicide, historically speaking,” she added. “In early modern America, suicide was linked to a stubborn unwillingness to accept one’s God-given fate and to the influence of the devil. Suicide was a felony and a sin: suicides were punished by the state, to whom their property was forfeited; by the church, which denied them burial in consecrated grounds or refused rites of burial; and by the community, whose members often desecrated the corpses of suicides, buried them without shrouds or coffins, or staked them to the ground at a crossroads.”

The beliefs and practices of some African slaves, however, challenged European and English traditions, Snyder said.

“Although it is difficult to generalize across the variety of ethnic Africans who were brought as slaves to the Americas, at least some groups viewed suicide as an honorable escape from enslavement, as well as a means of transmigrating back to their homeland,” she said. “When they took their own lives, they left bundles of food and clothing nearby, or outfitted themselves with ritual ornaments in order to speed their journeys to rejoin their ancestors. For these slaves, suicide constituted a ‘good death,’ while for English and European colonizers ‘self-murder,’ as they called it, was one of the worst possible ways of dying.”

Attitudes began changing in the late 18th century, when debates over suicide and slavery played out in newspapers and churches, in philosophical and political circles, and among ordinary Americans, Snyder said. “At the onset of the American Revolution, legislators sought to bring the laws that they had inherited from England into conformity with emerging democratic principles, and as part of this reform, Thomas Jefferson argued that suicide ought to be decriminalized.”

The terms of Jefferson’s argument, Snyder said, went something like this: “Was it in the state’s interest to obligate individuals to live? Should states maintain legal designations of suicide as a felony in order to deter people from suicide? Or, was suicide, while tragic, ultimately in the preserve of individual conscience and liberty over which the state had no power to discourage and no legitimate claim to intervene?”

Even today, Snyder said, “suicide is still uneasily situated on that divide between public interest and private will.”

During the years when suicide was decriminalized, she said, “the use of the suicidal slave became a predominant image in anti-slavery literature. It was a very effective print and visual shorthand to indicate all that was wrong with slavery. If the institution of slavery was so onerous that it led sane individuals to kill themselves, then it was an institution that needed to be eradicated from society.”

May 25, 2011

Terri L. Snyder is the recipient of a WAWH award. Photo by Karen Tapia

Terri L. Snyder is the recipient of a WAWH award. Photo by Karen Tapia