The Past and the Future: Dry

Southern California Has Suffered and Could See More Mega-droughts

October 23, 2007

by Russ L. Hudson

Southern California has suffered through a number of mega-droughts — severely dry years for a decade or more — in the recent geologic past. In fact, the climate trend since the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago, is for the climate to get drier, said Matthew Kirby, assistant professor of geological sciences.

“We live in an already dry climate that may be highly susceptible to mega-droughts,” Kirby said. “In fact, the recent 10,000-year period is characterized by a long-term trend toward increasing dryness.

“This is even more a concern because of global warming predictions for the Southwest, which suggest an increase in the frequency and magnitude of droughts,” Kirby added. “Our results provide an important baseline for assessing the amplitude of natural climate variability for comparison to present climate and future climate predictions.”

Kirby said those conclusions can already be drawn from his research on lake level — a proxy for actual precipitation — in Southern California, even though not all the data has been assessed. Many of his conclusions were printed recently in Journal of Paleolimnology in an article co-authored by his longtime collaborators Steven Lund of USC, Michael Anderson of UC Riverside and Broxton Bird of the University of Pittsburgh.

Those findings are affirmed by similar studies performed at the San Joaquin Marsh and Dry, Silver, Tulare and Owens lakes, as well as by climatological studies of tree rings, said Kirby. Each growth ring on a tree trunk represents a year, with larger rings indicating wetter years.

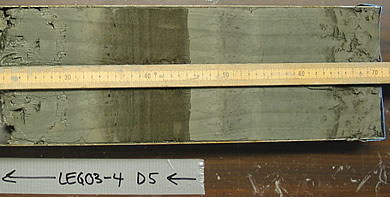

A section of a core sample with a wide band of sediment that could indicate there had been flooding that year.

The geological scientist has just received $64,812 as the second-year installment of a $104,741 National Science Foundation grant to study the Southern California's history of precipitation variability during the Holocene epoch. Knowing Southern California’s water past will help policy makers make more informed decisions about water in the future, said Kirby. Without enough water, California's economy, population and agriculture, especially Southern California, could not be maintained at its current level.

A specialized crane had to be used to lower the barge into the water.

As part of the NSF grant, Kirby, a Buena Park resident, has been going to Lake Elsinore and, from an equipment-laden barge, drilling for core samples from the lake’s bed. The cores have captured about 11,000 years of the lake’s history, Kirby noted. Lake Elsinore is a non-playa lake — a lake that doesn’t dry up each year — so the water that runs into it each year during the wet season washes in a layer of mineral and organic material, the scientist said. These layers can be read like pages in a book.

In the second-year study phase, Kirby will use geochemical and physical-sediment analysis to unravel shorter-term climate changes — those of less than a decade in duration — in Lake Elsinore during the Holocene period. The shorter-term climate variability is “the stuff that is more relevant, and tangible, to human time scales, rather than the much longer geologic time scales,” Kirby explained.

Kirby works not only with his long-time collaborators, but also with graduate and undergraduate students whenever he can. Currently, undergraduates Shauna Nielsen and Luissa Ivanovici are helping with his research. Both expect to complete bachelor’s degree in geology in spring 2008. Both have based their theses on the Lake Elsinore research, a pleased Kirby said.

Steve Lund, one of Kirby’s longtime collaborators, takes a turn on the drilling barge at Lake Elsinore.