Japanese American Living Legacy Project Documents

October 30, 2006

By Mimi Ko Cruz

When Susan Uyemura was invited to meet with Japanese-American Korean War veterans nearly two years ago, she didn’t know why they wanted to speak with her.

The meeting marked a new devotion for Uyemura, who quickly understood the veterans once they began recounting their lives.

“They wanted to tell their stories because they’re in their mid- to upper 70s,” she recalled. “They wanted to pass down their legacy, their history.”

Soon, Uyemura was meeting with the Korean War veterans monthly, and word spread that she was voluntarily recording their oral histories for posterity. Also wanting to tell their stories, veterans of the World War II, Vietnam, Gulf and Iraq wars, joined the Korean War veterans. Hence, the number of recordings grew, leading Uyemura to establish JA Living Legacy Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to documenting Japanese American history told by those who lived it.

Headquartered at Cal State Fullerton, the organization is run by volunteers who conduct oral history interviews before or after work and on weekends. Uyemura, who works on campus as a research technician and gerontology project coordinator, serves as the group’s chief executive officer; Natalia Yamashiro, an administrative assistant in CSUF’s International Education & Exchange Office, is president; Ray Uyemura, is the web technician, Kirk Yamamoto is chief information officer and Megan Tanaka serves as an oral historian. None are paid. They pay for their own recording devices and tapes, unless donated by friends and family members.

“This is a true labor of love,” Susan Uyemura said. “We’re in it for the long haul. We’re compiling three oral histories per week on average, and we have a total of about 65 so far. Everyone is so appreciative that we are doing this.”

|

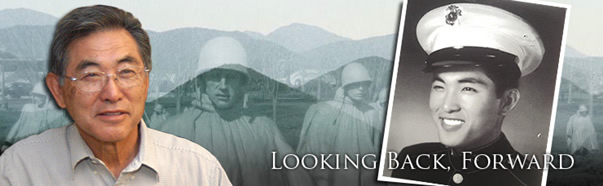

Indeed, said Robert Wada, a 75-year-old Japanese-American Korean War veteran who, with his parents and eight older siblings, was forced to live in an Japanese internment camp during World War II. His oral history is being compiled by the JA Living Legacy Project.

“I’ve got a whole pile of history of my life just sitting in boxes,” Wada said. “This is stuff that will eventually get all thrown in a box and forgotten when I’m gone, but this project is helping to preserve an important time in American history that Japanese Americans lived through. It’s educating future generations about what our generation went through.”

His own compelling story is full of details that grammar school history books don’t include, such as what it was like living in an internment camp as a young boy and, then, becoming a Marine and fighting for a country that harbored anti-Japanese sentiment.

For him, Dec. 7, 1941 — the day Pearl Harbor was bombed — is one of his most unforgettable days, Wada said, recalling the orders that rounded up 120,000 Japanese Americans, who were forced to abandon their properties and most of their belongings and live in internment camps.

“The internment camp where I spent three years, from age 11, was known as Poston, Arizona,” Wada said. “An entire family lived in one room that had one central light hanging from the ceiling. There were four rooms in tar-papered barracks over pine boards with holes in the floors. Each person was given a folding cot with a mattress bag that had to be filled with hay — the same kind you feed to horses…. The saddest moment for me in the camp was the day my father died when I was only 14.”

Wada’s story, along with the other Japanese Americans who are being interviewed by JA Living Legacy, are providing documentation that the organization plans to publish in book form and on a Web site that is being developed.

“We are learning so much about Japanese American history that has never been told,” Yamashiro said. “Some of the oral histories are on cassette tapes and others are on video and we’ve recorded up to seven-hour interviews.”

The stories are touching, shocking and raw. Full transcripts will be posted on JALivingLegacy.org by Veteran’s Day. The subjects range from Janice Mirikitani, San Francisco’s poet laureate; Richard Kihara, a Korean War veteran who was wounded twice; Lawson Sakai, a World War II veteran with the Army’s legendary all Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a highly decorated unit; Walt Tanaka, General Hideki Tojo’s translator during the war crimes tribunal; Glenn Tanaka, a third-generation strawberry farmer in Orange County; Art Ogami, a “No-No Boy” who refused to pledge allegiance to the United States and serve in the U.S. Armed Forces; George Sakasegawa, the Korean War veteran who was tortured as a prisoner of war for 14 days in 1952; and Iwao Aoki, a 90-year-old, second-generation chili pepper farmer.

Uyemura said her group feels a sense of urgency as it compiles the oral histories because most of the subjects are in their 70s, 80s and 90s.

“They’re dying every day,” she said. “Their stories are disappearing very quickly. We want people to learn from this important history that they are providing. We want researchers to have access to these stories.”

Several of the oral histories are on file at the Library of Congress.

Uyemura first became involved with the university’s Center for Oral and Public History in 2000 as a gerontology graduate student. She credits the center’s director, Arthur Hansen, for encouraging her desire to record the lives of elderly Japanese Americans.

Hansen, emeritus professor of history, called JA Living Legacy Project’s “grass-roots documentation of its own community history a very positive development in a variety of ways.”

He said it allows communities to take ownership of their heritage, while building community pride and underscoring the “vital point made many years ago by the great U.S. historian Carl Becker when he declared that ‘everyone is his own historian.’

“I think it is very uplifting to know that the JA Living Legacy project has inspired community historians to give freely of their time without monetary compensation,” Hansen said, adding that the information being compiled will be valuable to future generations.

“Being Japanese American, I feel a certain sense of pride and a desire to carry on the tradition of honor keeping our legacy alive,” Uyemura said. “I am very lucky to have found a group of people who feel the same way I do.”

Produced by the Office of Public Affairs at California State University, Fullerton.

Produced by the Office of Public Affairs at California State University, Fullerton.