Obliterating Obesity

Examining a genetic disorder to better understand problems related to excess weight

March 1, 2008

By Mimi Ko Cruz

Thanks to an $895,000 federal grant, researchers at Cal State Fullerton and the University of Florida are taking aim at a genetic disorder that causes one in 12,000 to 15,000 people to develop an insatiable appetite, often resulting in life-threatening obesity.

The disorder, Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS), is part of a growing national health challenge, according to researchers at Cal State Fullerton’s Center for the Promotion of Healthy Lifestyles and Obesity Prevention and the University of Florida’s College of Medicine. Faculty members at both institutions are exploring the disorder's links with child obesity.

Studying youths with PWS and contrasting their physiologic responses to exercise with those of other children, overweight and normal weight, could lead to intervention programs in the figtht against obesity, said Daniela A. Rubin, assistant professor of kinesiology and the study's lead researcher.

Cal State Fullerton’s Center for the Promotion of Healthy Lifestyles and Obesity Prevention helped secure the U.S. Medical Research Agency grant, which was sponsored by U.S. Rep. Ed Royce (R-Fullerton).

“This research will help with a growing national health problem,” said Royce, a Cal State Fullerton alumnus (Class of ‘77). “Obesity plagues all branches of the military, with an estimated 58.4 percent of America’s soldiers, 22 and older classified as overweight. Prader-Willi Syndrome is a complex and potentially devastating condition that, if studied, may help control obesity and reduce healthcare costs over the long run.”

According to Rubin, the study aims to understand how the genetic disorder can be managed through exercise.

“The idea is to see how children with Prader-Willi respond to two different kinds of exercise — aerobic and resistance-based,” she said.

In conjuction with Children’s Hospital of Orange County, blood samples will be collected and researchers at the University of Florida’s College of Medicine will look at metabolism, endocrine, hormonal and metabolic responses to exercise, Rubin said.

“Our goal is to figure out how these children respond to exercise, metabolically and hormonally,” she said. “We want to know how body fat is a player in this syndrome and the possible adaptations resulting from exercise. We want to understand the factors that will increase program feasibility, from a caregiver’s point of view, so we can design more tailored interventions.”

It’s a ground-breaking study in the eyes of Roberta E. Rikli, dean of the College of Health and Human Development. “Because PWS is the most frequently diagnosed genetic cause of obesity, it provides a valuable tool in the scientific study of obesity for genetically-induced and non-genetic obese populations.”

In the past two decades, researchers have established that people with PWS go through a complex progression of six nutritional stages from infancy through adulthood, said Daniel J. Driscoll, professor of pediatrics and genetics at University of Florida’s College of Medicine.

Working with Rubin, Driscoll and a team of his colleagues will perform a longitudinal study as part of the project, “to carefully delineate and dissect the six nutritional phases in PWS.”

Obesity is a multi-system disorder whose prevalence is increasing dramatically worldwide, Driscoll noted. “Particularly alarming is the increase in childhood obesity. We believe that by studying the cause of obesity in individuals with PWS and early onset morbid obesity, we will gain invaluable insights into the causes and nutritional pathways for obesity in general."

“The more we understand about the underlying causes of obesity, the more equipped we will be to treat and prevent this condition,” he said.

At the end of the study, Driscoll said, “we hope to have identified some of the unique signals that are associated with appetite regulation and correlate the findings with the Basal Metabolic Rate (the number of calories you’d burn if you stayed in bed all day) and body fat measurements. We will be able to determine how similar, and different, individuals with PWS are to others with childhood obesity.”

Susan J. Clark, director of endocrinology and diabetes at Children’s Hospital of Orange County and head of CHOC’s Prader-Willi clinic, and a team of her colleagues will be working on the project with Rubin and Driscoll. Other collaborators at Cal State Fullerton include Michele Mouttapa, assistant professor of health science; Dan Judelson, assistant professor of kinesiology; and Shari McMahan, chair and professor of health science and director of the Center for the Promotion of Healthy Lifestyles and Obesity Prevention.

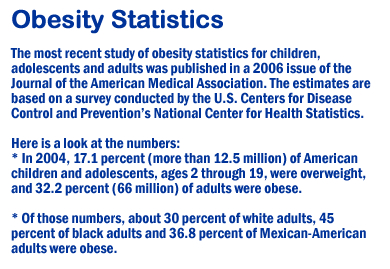

The university's center was created as a result of the dramatic increase in childhood obesity, which has become one of the country’s most urgent health concerns over the past decade. Recent reports from the CDC estimate that one in three U.S. children will become diabetic — largely due to obesity and inactivity — unless health habits change.

The Prader-Willi clinic at CHOC has experienced a drastic increase in the number of its patients since it opened about three years ago, Clark said. The numbers double each year, she said, adding that the clinic currently has 25 patients, from newborns to 21-year-olds.

“Keeping these kids active is very difficult, and if Dr. Rubin can determine what is the most effective exercise program for them, that will help us advise our families on activities that will be helpful in maintaining a healthy weight,” Clark said.