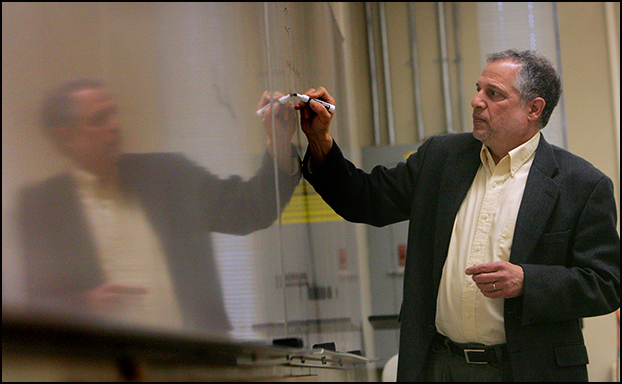

Caption: Raphael J. Sonenshein, shown during a class session last fall, recently presented a talk on governance reform at the Huntington Library. Photo by Karen Tapia

Caption: Raphael J. Sonenshein, shown during a class session last fall, recently presented a talk on governance reform at the Huntington Library. Photo by Karen Tapia

The Haynes Foundation Lecture at the Huntington

For Whom Bell Tolls

Recent Efforts at Governance Reform in California

Jan. 25, 2011 :: No. 1957

LATE IN 2010, Raphael J. Sonenshein, professor of political science and chair of the Division of Politics, Administration and Justice, delivered the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation winter lecture in the Huntington Library's ongoing series “California and the West.” In “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” Sonenshein offers a review of the recent history of governance reform in California. The following is a transcript of the live podcast accessible at no charge through the Huntington Library's iTunes University site. He was introduced by Robert C. “Roy” Ritchie, W. M. Keck Foundation director of research at the Huntington:

Introducing Raphael J. Sonenshein

Robert Ritchie: Good evening, and thanks for joining us on this cold December evening. Tonight is a John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation lecture we do once a year with the Haynes Foundation. If you don’t know the Haynes Foundation, they’re the oldest private foundation in Los Angeles, founded in 1926, the year after the Huntington. Well, actually, five years after the Huntington, but that's OK.

I can’t think of anything significant that’s been done in Los Angeles that has not been supported by the Haynes Foundation in terms of research into what we might broadly call the social science and history of Los Angeles and this region, and so it’s a very happy thing for us once a year to join with them in offering this lecture.

Our speaker tonight is Raphe Sonenshein. Raphe was educated at Princeton for his A.B. degree and then went on to Yale. He’s currently the chair of the Division of Politics, Administration and Justice, and director of the Center for Public Policy at California State University, Fullerton.

I don’t know anybody, well, there are a couple of people in the audience, who know as much as Raphe does about Los Angeles politics, but he has certainly published and written a very great deal. His first book, “Politics in Black and White: Race and Power in Los Angeles,” received the 1994 Ralph J. Bunche Award from the American Political Science Association.

He’s also been very much involved in charter reform in Los Angeles, and served as executive director for the city of Los Angeles Charter Reform Commission, 1997-99. Out of that came another book, “The City at Stake: Secession, Reform and the Battle for Los Angeles,” published in 2004.

He has subsequently been involved in charter reform for the cities of Glendale, Burbank, Culver City and Huntington Beach, and he continues as executive director of the Los Angeles Neighborhood Council Review Commission. He is also a noted teacher/lecturer at Fullerton, been named best educator by the Associated Students and distinguished faculty member by the School of Humanities and Social Sciences. In 2005, he received a California State University Wang Family Excellence Award. In 2006, he was named first winner of the campuswide Carol Barnes Award for Teaching Excellence and is one of the co-winners of a major Haynes grant. Out of this has come “Los Angeles: The Structure of a City Government” and even more publications. I could go on.

I’m very happy to introduce Raphe Sonenshein. I don’t have to pull out this piece of paper because it’s right in front of me: “For Whom Bell Tolls: What Can Be Done About Local Governance in California.” I told him he can‘t say a lot of bad things about Bell, because I went to Bell High School. But that was in a different era. Ladies and gentlemen: Raphe Sonenshein.

Raphe Sonenshein: Good evening, everybody. Nice to be here with you all, especially during this holiday week when the United States Senate is trying to decide if they can show up to do business — it’s nice that you’re all here. Woody Allen once said, “90 percent of life is showing up” so, it’s wonderful to have you here tonight.

Roy has made me feel terribly guilty by announcing that he went to Bell High School, but trust me, Bell isn’t going to look very good by the time this evening is over.

I‘d like to thank the Huntington Library for sponsoring this event — it’s really a great honor to do this and to be designated to do this — to thank Roy and his great staff, but also to thank the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation.

California and the Haynes Foundation

It took me many years to get that correct, and many of my colleagues mix up the names. I had one colleague who referred to the John Dora Haynes and Randolph Foundation. Actually, they had sent in a draft proposal, and I caught it before it went in, which I thought was not very good. The Haynes Foundation has been wonderful for me, and I imagine there are a few people in this audience who can say the same thing, such as Tom Sitton (curator of history at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, and author of “John Randolph Haynes: California Progressivism” and “The Haynes Foundation and Urban Reform Philanthropy in Los Angeles), who’s sitting in the back.

In 1988, when I began to write about Tom Bradley — who I thought was very interesting but people in political science did not think was very interesting, at least in part because he came from a city called Los Angeles which, by definition, was not a very interesting city -- I called Diane Cornwell, who was then the administrative director of the Haynes Foundation, told her my sad story and said, “Of course, I know I can’t find anybody who cares about this and will support this.”

And she said, “I care about it. We care about it. We will support it.” They gave my first of a number of grants that basically have made me a happily and wholly-owned subsidiary of the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation.

Her work, notably carried on by Bill Burke, who is also here, with whom I’ve had a very enjoyable working relationship. There is nothing like the Haynes Foundation in rest of the United States. New York does not have a Haynes Foundation for New York research. Chicago does not have a Haynes Foundation for Chicago research.

This state that has struggled so hard to get recognition in the academic and intellectual communities of this country would not be where it is without the fact that we uniquely have this Haynes Foundation. So I’m very proud to be a junior friend of the foundation as they’ve been such a great friend to me. Let's give a moment’s recognition to the Haynes Foundation.

The Idea of Local Government

I decided tonight to speak about something you may have heard a little bit about, the scandal in Bell, California. You would have heard about it if you lived in, I don’t know, Timbuktu. The scandal in Bell has been covered not just here, not just in California, but nationwide, in Europe and in Asia. The story of Bell, California, has become, unfortunately, the cautionary tale of all time about local government.

But I wanted to take a step back today and look at the big picture of local government in California and in the United States and find out what this Bell story really tells us. It may tell us more horrifying things than we want to know. But it may also provide a window into how we can make local government better, which in some ways means learning the lessons of how to really reform government, not just to react to the crisis that’s right in front of you.

I’m going to draw on my experience as a reformer of and participant in local government that really began when I was a college senior. My academic adviser said he was on his way to Newark City Hall to help the new African-American mayor, Kenneth Gibson, and did I want to come along? And I said, “You bet.”

You have to understand -- in those days, I had hair that was about a foot higher, a ripped shirt and blue jeans. But he just packed me up in his car and we went to Newark City Hall, and I was completely hooked on city government from that day forward.

I came to Los Angeles in 1974, went to work for Tom Bradley as an intern, then for Dave Cunningham in the city council, and to this day have considered myself a friend of these local governments. I came to know the people intimately who worked in local government. I came to understand how hard they were working. And I learned that in local government, you are always where the rubber meets the road.

Learning How to Govern

You’re in the office where the people come in and yell at you, and no matter how much people at higher levels of government complain about how hard they’re working, they have no idea what it is like to be out there every day in the community and how exciting it is and how, at times, terrifying it is. That’s the context for what we’re going to talk about today.

In our country, we have an ideal of local government, and believe it or not, there’s a book called “Guide for Charter Commissions.” It’s actually a book I value and have used many times in my charter work.

This line from the National Civic League has stuck with me: “It is in cities, counties, towns and villages that the people have to learn the practice of democratic, responsible self-government.” This is peculiarly American. When you go around the world, the locus of democratic growth is rarely at the local level. We have a very strange and unusual system.

I think it’s a wonderful thing. I almost wish it had actually been in the Constitution, because the Constitution of the United States makes no mention of local government; it only makes mention of federal and state government, which has been an enduring problem for local government.

The Cradle of Democracy

Think of the contrast here. We have nothing in our constitutional structure about local government, yet our expectation is that this is the cradle of our democratic experience. It’s a bit of a problem, but it also explains why Americans actually trust local government. You’ll find that’s been a bit of a wrenching experience because of the example of Bell.

A 2010 CNN poll found twice as many people trust their local government as trust their federal government. Gallup has recently reported that 72 percent said that they trust their local government; 67 percent, state. The farther up you go up the food chain, the less trust there is in those levels of government, and this has been repeated again and again.

But of course, to add more to the contradictory nature of local government, we don't love it quite enough to actually vote, because voter turnout is the exact reverse of this. We're most likely to vote in elections involving the level of government we trust the least, which is federal, and then down until you get to the local level. We'll talk a little bit about why that is.

But a cautionary note is that's particularly true in the West and in the Southwest, where political reforms championed by heroes of ours, such as John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes, established systems of political reform that inadvertently, or for some people, intentionally, made it more difficult for people to participate, which strikes me as yet another irony of local government.

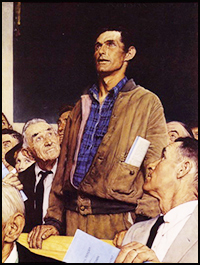

Caption: Norman Rockwell's "Free Speech"

Caption: Norman Rockwell's "Free Speech"

But if you put all this together, we have a kind of Norman Rockwell moment here. In his series of paintings, "The Four Freedoms," Norman Rockwell did one about "Free Speech" that really did capture his time. If you look at this picture, there is so much in this picture about our aspirations of local government.

Trust me, this guy could not stand in the well of the House of Representatives and ask to be heard, but he could be heard in front of a city council of a large city or a small town. Notice that his neighbors are listening attentively. This may not reflect your experience at city hall.

But he's a busy guy, but he's made time to show up. In a nutshell, doesn't this show you our aspiration almost visually, truly visually, of local democracy? That an ordinary person can stand up and be heard by people with power and notice, be listened to by neighbors, one of whom is considerably more formally dressed than he is but is looking up to him as a fellow citizen?

Bell has caused us some problems, and I’d like to show you the contrast. Norman Rockwell, take a moment. Norman Rockwell meets Robert Rizzo.

The Good, the Bad & the Ugly

I thought on the way in that we'd talk about the good, the bad and the ugly. Some people actually capture two of those, rather than just one.

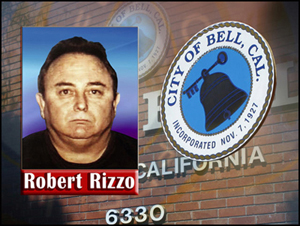

Caption: Robert Rizzo's booking photo taken by the Huntington Beach Police.

Caption: Robert Rizzo's booking photo taken by the Huntington Beach Police.

This is Robert Rizzo's booking photo in Huntington Beach, where he lives in a fabulous mansion, but was arrested on a DUI. This is the most famous picture of the center of the scandal that we're going to start with tonight, which is the scandal of Bell, California.

You are looking . . . it's hard for me to say this . . . I have many friends who are city managers and city administrators. This is a city administrator of the city of Bell.

On July 15, 2010, two reporters named Jeff Gottlieb and Ruben Vives of the Los Angeles Times broke a story on the front page of the newspaper that only began to scratch the surface. That story said that the city officials of Bell are earning colossal, unheard-of, astounding salaries. I'm only here to tell you that they were underestimating these salaries, as they did further work and found that they were actually pulling down considerably more than this. They proved, by the way, that even a newspaper which has fired enough reporters to start their own Pulitzer Prize pool can still do fantastic work. I would not be totally surprised if these reporters did not win the greatest award in journalism.

I asked Jeff Gottlieb how they got themselves going on this. He said they were studying Maywood. Everybody knew Maywood was a mess, so they were down at Maywood and somebody said to them, “There’s the beginning of some digging by investigative authorities in Bell. You ought to check it out.”

So they went over to Bell and found that everything was completely stonewalled. They had to do old-fashioned, basically shoe-leather reporting. I discovered how stonewalled Bell was when I was invited to go on KPCC's Airtalk with Larry Mantle and talk about Bell. On a hunch, I called Bell City Hall after I tried to get through their website, which basically had pictures of the ocean and no information about the government. I finally got a person on the phone. I said, “Could I see the city charter?”

She said, “Sure.”

I said, “Great -- how?”

She said, “File a Public Records Act request, mail it in to us, and we’ll consider your request,” which, of course, I immediately reported on Larry Mantle’s program. We called the secretary of state, who faxed us their charter. You could not get the city charter from Bell.

So what did this story reveal? The city manager, Mr. Rizzo, was earning $787,637, almost twice the salary of the president of the United States. The average salary, by the way, for The average salary for city managers in Southern California runs around $210,000, and that includes the large and well-to-do communities. It later turned out, further digging found, this man had successfully obscured the fact that he was actually walking away with close to $1.5 million.

The police chief was earning $457,000. He had formerly been the chief in Glendale and was lured over to Bell with an offer to more than double his salary. According to the LA Times, he was warned by a colleague that that’s probably too good to be true, which reminds me of the young lawyers in the Grisham novels who get hired by the mob firm for a million dollars a year, and someone says, “Maybe that’s too good.” Well, he’s going to pay the price for that.

The assistant city manager was making over $376,000, and those three alone were pulling down more than 10 % of the city’s budget in their salary. The city’s budget was only about $15 million.

Tip of the Iceberg

But this was only the tip of the iceberg. More and more details emerged the more threads they pulled. First of all, we discovered that they had built in massive pensions for themselves on three different levels. They were redefining themselves as public safety officers, which is a classic technique by which local officials enrich themselves, since public safety officers earn better pensions because of the risks that they take.

They added an additional supplement pension paid for out of Bell’s own money, in order to circumvent state pension laws. Again and again, you’ll see how this group managed to evade and avoid state laws and regulations.

Among other things, they began tapping into the general fund to provide large loans to top city officials and to members of the city council. None of those loans were approved by the city council; they were simply directed by the city administrator, who gave a large loan to himself, and in some cases, apparently used the city budget to then pay off the loan.

We then discovered that the members of the city council were earning close to $100,000 a year for part-time service, which consisted of meeting once a month, under the category of nice work if you can get it. What I loved about it is they later said that, of course, they’re working incredibly hard. When asked if they knew what the administrator had done, they said, ”Well, he never asked us. We never made any decisions.” It was a little difficult to square those two things.

In addition, they began to issue no-bid contracts in violation of city law, including contracts for current city officials and ex-city officials. One way they were able to do this is, they created a sham charter election, which as a charter guy really offends me.

In 2005, the state of California passed a law because of abuses in a city called South Gate that you may have heard about. They had been paying themselves excessive salaries by putting themselves on commissions other than the city council. So the state passed a law that a general law city cannot do that.

So therefore, the city administrator approached the council and said, “Then let’s become a charter city, and then we can pay ourselves whatever we want.” The problem was, if anybody had found out what they were doing, they would have been in trouble.

Putting a Price on Government

So they scheduled the election for a few days past Thanksgiving, made it an independent stand-alone election without the county’s involvement. You can’t find this election on the county’s website — I tried — and fewer than 400 people voted in this election, 239 of them by absentee. There’s evidence that city officials were collecting in violation of law, basically, those materials that they were sending around.

Let’s slow down a bit, because I’m just too excited. Bell, California … before we go further, this is a city of only 36,000 people. You might wonder why the city administrator needs almost twice the salary of the president of the United States. When asked, he said that it’s a very hard job.

The city is 90 percent Latino, 53 percent foreign-born. Thirty-six percent of adults have as much as a high-school diploma; 4 percent have a bachelor's degree. So as a city, it’s a poor city, it’s an immigrant city, it’s a city with limited education — and it’s only 2.5 square miles.

It’s one of the smallest cities of its population size in the United States. It’s near Vernon, Maywood and Commerce, which have had their own problems, and the city budget is approximately $15 million.

One reason we didn’t really know very much about Bell is we were so busy looking at Vernon and Maywood and South Gate, which had terrible problems of corruption. Vernon, you may know, has been run for decades by a family that has limited the population of the city to 90 people, all of whom live in city-owned housing at cut rates and vote to keep the incumbent family in power despite the fact that numerous members of them have been indicted and imprisoned.We recently found that city officials have been traveling around the world first class and staying in five-star hotels. It’s a total catastrophe.

Maywood was in such trouble that they abandoned their entire city workforce and came up with the brilliant idea of turning the management of their government over to Bell. This is what in social science, by the way, we refer to as a “duh” observation, that probably Bell was not Maywood's best choice.

Raiding the Public Coffers

Now, the scheme in Bell to basically grab as much money from the public and from the budget as possible had the following elements to it. Number one: Jack up local property taxes as high as possible. This low-income community pays some of the highest property taxes in California.

Then when they decided to supplement their pensions, they passed a supplemental property tax increase that was in direct violation of state law. It’s basically an illegal tax. You may wonder how they got away with it as long as they did.

City council members and the city administrator were then put on city commissions where they were paid thousands of dollars a month for commission meetings that lasted one minute. The meeting would start at 7:21 and then adjourn at 7:22, and they would walk away with thousands of dollars. They were able to do that because they had a charter which allowed them to get around state law.

The harshest thing is they flat out cut back on city services and told local residents that we’re in a tough crunch here. Everybody’s got to make sacrifices. So they laid off police officers, firefighters, other workers to cut services to the bone to maximize the money available to steal.

As something I recognized from the East Coast, they shook down local businesses for fees and charges. They would go in and basically say, “Don’t you know you owe us for this, you owe us for that?” I would say this is not a big step from that to protection money, which I remember from the East Coast. One business was fined because people were parking on private property, and the police came and fined them and collected those fines.

Maybe the most … I don’t know. There’s so much that’s despicable, it’s hard to choose. They began to make money from towing, and the way they did it was they began towing cars in the hopes that the cars they would tow would belong to undocumented residents who did not have driver’s licenses.

Entrepreneurial Thievery

They would charge five times the normal towing charge and basically go out and look for people who met a profile of people who would be undocumented residents, would not have a license. They would grab their car, impound it and then charge $500 or more to get it out. They were earning $800,000 a year in towing charges to supplement the money coming in.

They issued bonds that were not backed by city revenue for buildings that were never built. To this day, I don’t yet know where that money went, and I think the state is very curious to know where that money went.

Just to show you how careful they were to steal things, there was property tax money that was supposed to be put in a debt-service account. I mean, really. This is what you do to pay off certain debts, you have to put it in an account?

But Mr. Rizzo’s contract only would stay in effect if the city maintained a certain balance in the general fund. So in violation of law, they took the money out of the debt system and put it in the general fund to make sure there’d be enough money so he could get his additional payments.

No big contracts, loans from the general fund, the city staff and council members, shifting pensions, the charter election. Then you ask yourself this question: Could it have gotten worse? You’d be amazed how much worse it could have gotten if the Times hadn’t gotten involved: because not long ago, as I mentioned, the city of Maywood decided to turn to Bell for help.

The Auditors Proved No Match

Now, you might ask yourself, why? But consider this: Bell had a very good reputation. God knows how.

Their audits, which are now being conducted by their outside auditor, were so wonderful that they won awards for audits. I mean, I don’t know what to say, except it makes me wonder about auditing.

I hope none of you are auditors and take offense, but if Bell could have a good audit that would win awards, such that Maywood would say, ”Well. There‘s a beacon of good government in our area. Let us join with them.”

So Miss Spaccia, who is the assistant city manager, was sent over to Maywood to run Maywood. I guess she had a little extra time on her hands. And Maywood paid Bell $50,000 a month to run Maywood. All of which went into the pot, for more money to be sent off to these officials.

It turned out they had another plan. They were going to go to Cudahy, Maywood and a few other cities and establish a super police agency, presumably under Bell’s leadership. Where that whole region would sooner or later become — I don’t know — Robert Rizzo‘s Lakewood plan.

Imagine where this was heading. They weren’t going to stop. They were going to have three or four cities working with them. And then he'd have three more budgets to run into the mess.

The Question Everyone Asks

How on earth did they get away with this for so long?

Number one, they stonewalled everybody. And most people get frustrated and give up when they’re stonewalled. They lied. When a public records act request was made to Mr. Rizzo about his salary, he just put down a false number and sent it back. People assumed he’d be telling the truth. They purposely confused people. They wrote contracts with ambiguous pay periods, so you’d have to have a Ph.D. in math to figure out the annual salary. And they wrote each other emails about that.

They avoided public votes. If they wanted to do it themselves, they didn’t even ask the city council. They just delegated everything to the city administrator. They almost got away with this; although sooner or later, you have to think something would have come of this. But it took a while.

A Catastrophe for Local Government

And then when it happened, everybody just went crazy. The reaction was unbelievable. The media attention — oh my god, I think this is one reason that proposition 26 passed, which made it more difficult for local governments to raise fees, which I think is going to turn out to be a catastrophe for local government.

It was pretty hard after Bell, to go out and make a case to the voters, for more flexibility for local government.

The Attorney General … this was a godsend for Jerry Brown. He was running against Meg Whitman, who as you know had more money than god. And he had to show that he had a job and she didn’t. He filed a civil lawsuit against these Bell officials that was very effective.

The District Attorney, who was running for Attorney General, filed criminal charges. The U.S. Department of Justice weighed in on the towing issue. The Securities and Exchange Commission is now investigating the bond sales.

I hope one of the things they’re going to look at is how the bond rating agencies gave them the support to issue bonds, given what was going on in the town. It does make you feel like nobody ever asks anybody anything. Is it rude? You wonder, isn’t it a case of rudeness, excessive politeness? The League of California cities and the International City County Management Association mobilized with the three word phrase, “We’re not Bell.”

How Much is Too Much?

Now when I heard this, as a local government guy, I was very upset. Because I work with honest people every day in local government and I know exactly how they felt. They went to work the next morning and people called them up and said, “How much are you stealing, because you all do it?”

Well, the league got together real fast and did a survey of city managers in California. And found that the average city manager salary in California was just over $210,000 to manage an entire city government, which is pretty reasonable. It’s pretty much accepted that that’s the correct range.

They issued statements, you know, the Bell people kept saying, “We’re just normal. This is what everybody does.” And you can imagine how city people took that.

Not waiting, State Controller John Chiang immediately created a mandatory database, called the Local Government Compensation Report, which you can read online (http://www.sco.ca.gov/ard_locinstr_lgcomp_forms.html), showing you what cities pay their officials.

LA city controller Wendy Greuel created a city version immediately and put it online (http://controller.lacity.org/index.htm). And it’s easy to find at City Hall.

To get a little bit ahead of the story, the Los Angeles County government, which in my opinion is one of the most closed and unresponsive governments in Southern California, immediately announced that it would violate the privacy of their employees, to release their salaries.

In the middle of this, this is what they decide to take as their position. Eventually, of course, they had to back down, but you wonder why was that their first reaction.

And now along comes the legislature. Now you know everything is just going to go to hell. Because the legislature comes in and they’re going to reform everything and fix everything and they begin throwing all kinds of bills into the pot. But will that solve the problem?

Sonenshein's Guide to Reform

I didn’t want to put Raphe’s rules for reform but that’s really what these are, some rules for reform.

When you look at the reforms that are out there, I put down five things to think about. And it throws almost everything the legislature came up with out the window with this list, except one item.

Rahm Emanuel, the unlamented chief of staff of President Obama, did say one good thing. Never waste a crisis.

Most good reform comes out of trouble. It doesn’t come out of good things. It comes out of trouble. But reforms that only fix the crisis directly are also a waste, because you’re still fighting the last war. You’re saying let‘s prevent that bad thing from happening again.

Reform should always advance good and responsive government. And, in general, you’ll never succeed in devising reforms that assume everybody’s good or everybody’s evil. Most governments and most people are kind of in the middle on that, and that’s the best place to look for reform.

And lastly, don’t expect the legislature to figure out one, two, three and four, because the purpose of a legislature is to respond quickly and solve a problem, and move on to something else. By the time they’ve done that, they’ve already forgotten about it. And most of the solutions are going to violate these laws.

So evaluating the reforms we have heard — and then I’ll present some of my own.

Several Simple Rules

Number one, transparency is always best. L.A. County was fighting a losing battle, hiding salary information. Look, if you’ve got a contract with a public agency, it is public information. There is no way around it. There’s no reason to fight it.

I know when our university system decided to make a phenomenal battle over whether to reveal Sarah Palin’s speaking contract at Cal State Stanislaus, this was a losing battle. Actually students had to dig in the dumpster to find the contract. The truth of the matter is it’s all going to come out eventually. But keep in mind, transparency is not enough. Because very often, the data you see online is sent by the cities themselves. And one thing we learned from Bell, is that occasionally there will be devils.

Most will tell the truth, but Bell’s attitude would be transparency’s great. And they would just make up an acceptable number and send it in. And it would show up and they’d win awards for their audits. The fact of the matter is, you can trust most local governments to send in the correct information. But I’m here to argue that occasionally, you have to go in with the forensic people. And pick some cities at random and look at every single check. Doesn’t matter if you pick a good city or a bad city, but this is the same reason the audit firms got in trouble. The same reason the Wall Street firms got in trouble with this city, is they took the city's word for everything.

What I worry about is that people will assume their city is crooked. And I can tell you from years of experience in California, the odds are your city is not crooked. But the fact is, we can’t afford too many Bells.

Next, you can’t expect the district attorney to monitor local governments, 88 alone in Southern California. They want to go after people who rob and kill people. That’s what the DA is good for. The DA is not good for finding out if local governments follow the Brown act. The DA doesn’t want anything to do with that.

And secondly, do you really want to go to prison for a felony, violating the Brown act, and explain that to your cellmate? “Yeah, actually we didn’t provide adequate notice for a public meeting. What are you in for?” “I killed three people.”

If you’re in for that, I recommend that you come up with a better explanation.

The only legislation that I think was worth anything that the state came up with was by Assemblyman Kevin De Leon (D-Los Angeles), who did something legislatures are good at. They wanted to refund the money the city had stolen in property taxes from people — almost $3 million — but state law said that money had to go to the schools. As worthy as schools are, it made more sense to give it back to the people they stole it from.

He put a law in — Governor Schwarzenegger signed it, and the governor who doesn’t always sign the right things — that, in my view, did the right thing: He turned down all the bills that came through on Bell except that one and signed that one. Those people are going to get their money in a matter of weeks. That was good.

California Can't Afford Too Many Bells

I didn’t like the bill that was going to force cities to not have redevelopment money unless the attorney general certified that their city salaries for council members were OK. This struck me as fairly nutty.

The fact of the matter is, you don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater. American cities took 100 years to develop home rule and the ability to make charters, and Bell’s experience is not enough to throw that out.

In 1872, a judge in Illinois named John Dillon announced that local governments should have no authority, they were creatures of the state, and the reason he did that is because of the municipal corruption of his time. It took decades for cities to develop home rule and come out from under Dillon’s rule. This is no time to go back to some of the solutions I’m hearing in Sacramento that would make cities wards of the state.

I found it particularly entertaining. I was on the radio with one of the members who had produced one of these bills, who then, when I asked him about it, said he actually hadn’t produced that bill. So it was difficult to argue with him.

But I was pointing out to him that you guys haven’t even passed a budget yet. That was not well taken. Here you are with the latest budget in the history of California, and you’re explaining how you’re going to run 480 local governments in California from Sacramento. I'm not sure they thought about this.

The state is already taking money away from local governments. In truth, cities need more flexibility, not less. This goes against the grain of what people are saying about Bell. For example, I don’t believe any jurisdiction in California should require a two-thirds vote to raise revenue in any way if a majority of the voters want to do it.

If you’re going to expect local government to reflect the people’s vote, then the people’s vote has to matter. I’ve never understood, by the way, why people think that local governments are dying to raise taxes, given that they have to face the voters.

Prop. 26, which just quietly passed this last election overshadowed by Bell, now requires a two-thirds vote on many state and local fees, which previously had only been true of taxes. I think it’s going to have a terrible impact on local government, because ultimately, in a recession — the time we’re in — it’s the local governments that are taking the heat for the fiscal crisis that we’re in.

Taking On the Deeper Problems

So I guess I’m going against the grain. Don’t do reforms that make it harder to be a city government; in fact, think quite the opposite. But there’s more. There are bigger questions we could look at. We could ask ourselves this: Are there deeper problems in the structure of California’s local governments? And I’d say the answer is yes.

Number one: Do we have, perhaps, too many local governments? Certainly, in Southern California. When you see a city like Los Angeles surrounded by 87 independent communities, each of which can frustrate the will of the four million residents of Los Angeles, I think that has some problems.

When cities go bad and are truly bad, like a city like Vernon, I disagree with the Los Angeles Times and others who say that Vernon should not be disincorporated. I believe the city of Vernon has proven now decade after decade — this is much longer than Bell — that it should not exist as a city. It is basically a family corporation using the power of municipal incorporation for theft. That strikes me as not particularly a good reason to have a city government.

Disincorporation for other cities, Rick Cole, former well-known city manager and scholar, recommends that all of these cities be disincorporated and put into a super-city of say, Bell, Bell Gardens, Maywood, Vernon, and then let everybody vote for the leadership of those cities. I wish him good luck. I think it’s a nice idea. I think it would be very difficult to do. I would first start, though, with breaking up Vernon.

A historian might ask, why these cities, and, it may not sound very gracious, why, they just aren’t part of the city of Los Angeles in the first place. Los Angeles should have annexed these cities in the 1950s and 1940s in order to increase the tax base and become like cities in other parts of the country, but they did not.

Now I’d ask you a question that I was afraid to actually put in writing, because I was afraid it would get passed around and I’d have to really answer for it: Are local council members overworked? The word I didn’t want to put in was “underpaid” because I felt I’d get too many emails from angry people.

I work with city councils all the time, and Bell is the example of an underworked, overpaid city council. But increasingly, we've created a very odd profession called city council member in California. They’re supposed to be volunteers. They get very small salaries. They’re supposed to put their own work aside, put their home phone number in the phone book, because their constituents want to hear from them all the time.

Guess what? Only a small slice of people can then consider being a city council member, because this is one of the problems of reform. We created a wonderful system called the council manager system of government that requires thoughtful, disinterested council members supervising a highly professional city manager.

If we don’t give the city council enough to do, the manager runs everything. If we give them too much to do, they hypermanage the city manager. So how much work should they be doing? If I ran a zoo, I would pay them less, but make them work a lot less, not have their phone numbers in the book, and not have their constituents screaming at them when they don’t provide instant responsiveness, or I’d pay them more and expect more of them.

Instead, what we’ve created is semi-amateurs. But those positions are really not available for people who are not independently wealthy, professionals, retired or have the ability to serve on those councils.

Hold County Government Responsible

My next question is why on earth do we let counties off the hook? We’ve all got complaints about our city government, as if the city government is the beginning and end of all the problems in the universe. Oh my god, county government, there are a couple of issues about it.

Number one, country governments are almost totally impervious to public pressure. If you want to raise hell, go to city hall; don't bother going to the county hall of administration.

A number of years ago, the L.A. County supervisors put in a limit of about 30 seconds for public comment, until they were embarrassed by a comedian who was one of these people who could say 10 minutes of things in 30 seconds and did a brilliant 30-second comment. It got some publicity, and they got rid of that.

They have been known for violating the Brown Act. They didn’t want to release the salary information. Who on earth knows anything about it? If you are a working-class resident of Southern California, all of your interests are represented in the county, not in the city.

The social services come out of the county, and no one has a clue what they’re doing or how they’re allocating it. Each supervisor in Southern California in LA County represents two million people, which means they represent nobody, because that’s ridiculous. You can't represent two million people in a legislative body.

We have only one elected county executive in the entire state of California, and that’s in San Francisco, because San Francisco is a combined city-county, the only one of 58 in California.

I would really like to see a change in Southern California. Actually, Don Miller, back in the ’70s, with a group funded by the Haynes Foundation, worked on this problem. There ought to be an elected county executive in Los Angeles County who we can hold accountable to figure out what on earth is going on in that area, because what we have in our reform system of government is a silent voting crisis.

Homeowners Make Up the Majority of Voters

We don’t want to talk about it, but in the local elections, the closest to us, the electorate is very narrow. It’s more middle class. It’s less diverse. It’s more homeownership. In the city of Los Angeles, a third of the people are homeowners, and two-thirds of the voters are homeowners. That’s a pretty colossal difference.

If you look at two council districts in Los Angeles: the First District on the Eastside, represented by Ed Reyes, is a Latino working-class district that had 60,000-some-odd voters in 2009, and in the mayoral election, with a Latino candidate running for re-election, 11,000 residents voted. In the Fifth District, Westwood on the Westside, a white middle-class, well-educated district, there were 167,000 registered voters in that district, and 35,000 voted. You might think, well, there must be something about the people. No. Look at the presidential election of 2008 with Barack Obama on the ballot. In the First District, almost 43,000 people voted.

So before people get into ideas about why people vote, cultural explanations, all of this, there’s a very simple thing: If you have an election that’s structured to bring more people out to vote, more people will come out to vote. Local elections in California, being non-partisan, held in odd-numbered years at odd-numbered times — you couldn’t design a better system to discourage working-class and minority people from voting in local elections. Then you switch to the party-based presidential election, and out they come. They’re out there at the polls.

So we hear some proposals on this. The Public Policy Institute of California has proposed that local elections in California should be moved to presidential and statewide election years, even-numbered years. They found that that alone would bring millions of new voters to local elections in California.

I’m not sure I think that that’s doable. For one thing, here’s my worry: as a political scientist, I love it; but as a local guy, I tend to think the local race will be at the bottom of the ballot, and you’ll end up voting based on slate cards put out by organizations. It may really end up being more people voting, but not very good for the locality. Every charter commission I’ve been with has turned down this idea when brought before them. I think it’d be very hard to do it.

But Kathay Feng, some of whom you may know as a director of California Common Cause, has come up with an interesting idea. I asked her permission — “Could I present it tonight,” and she said, yes. What if in the odd-numbered year, all local elections in California were held on the same day, that you had essentially a local democracy day in California where everybody talked about their community?

Getting Voters to the Polls

None of these elections like, oh, on March 5, we’re going to have an election on this, with five people showing up to vote; everybody would have a local democracy day in California. I actually believe this could work, I believe it could save some money, and I believe it would bring many, many more people out to the polls, because you wouldn’t have stand-alone elections, which are really death to participation.

I’d argue that if we elected the county executive, more working people would come out to vote. If we reduce the two-thirds requirement for taxes, I believe that would have a very positive impact as well.

I’d also add a new idea. I believe every county, and especially Los Angeles County, needs a county ethics commission, not the county government, because it should watch the county government as well. It could do in a civil way what the district attorney cannot do in a criminal way, which is to criminalize everything about local government.

I believe this would be the place you could go if your local government is not following the rules, is not being transparent. You could bring in all kinds of other folks. The City Ethics Commission in Los Angeles has done a great deal to clean up Los Angeles politics. It has a long way to go.

But I am tired of thinking that people in places like Bell and Maywood have to pray that a Los Angeles Times reporter has the willingness to stick around and ask some questions. If they hadn’t, who knows how much longer this would have gone on?

Everybody else is going to lose interest anyway. The legislature will move on to other things. Everybody will have gotten elected to office and think about other things to do.

A county ethics commission would replicate for people outside Los Angeles some of the benefits Los Angeles residents have gotten from living in a big city. I don’t see why the other six million residents of L.A. County should be excluded from that.

Can Government Reflect Both Ethics & Equity?

This leads to my conclusion. As we move into the 21st century and we’re willing to critique even our greatest reformers in California, I want to ask you a question: Can we have both ethics and equity in local government?

I think this takes us way beyond Bell. I don’t think we should let Bell divert us from that question. It goes something like this. We could have clean government in California, and I would argue, by the way, if you did do forensic audits around California, you’d be pleasantly surprised that most local governments are pretty cleanly run, moderately efficiently run, not doing all the things that were being done in Bell. Despite the fact that you all probably think your own city is a gang of thieves, the odds are that they probably are not.

However, it would not take you much research to discover how few people are participating in your city government; how few people are participating in elections; how often the same people appear at every public meeting, making the same points again and again; and how many young people are not showing up at those meetings; how little energy there is in that local democracy; and how few people who are not middle class or better are really able or encouraged to participate in our system, which has impacts for equity.

If our counties are not responsive to voters, what does that mean for people who depend on each county for social services, but have no access to that level of government because our reforms have kept the county and the city so separately?

Can working-class residents get good government? Can middle-class people get good government? Because everybody deserves ethical government, but we also deserve equitable government.

Back to the Future?

I want to go back to the figure that I began with. Not him, this picture. I asked myself a question as I was preparing for tonight, which is who would this person be today? Who would this person be today, and who would we want this person to be today? Would we want to change anything in the picture?

When Norman Rockwell did these paintings, this was still a largely working-class country with a growing middle class that was about to become a pretty spectacularly successful middle class. One of the great middle class and social developments in the history of the world was what developed in this country.

The gentleman to his right with a tie would today be much more likely to be the person standing up and speaking at that meeting. But look at how the person speaking is dressed at a time when a person might show up at a meeting looking more like a working man or a working woman coming out for democracy.

That person today would be Latino. The modal person standing in that position socioeconomically in Southern California is not white, is not middle class, but is Latino and working class. The question that I would challenge us with in the long run, way beyond Bell, is to ask ourselves what would it take for our system of local democracy to be inclusive enough?

What changes would we have to make that the person standing in the Norman Rockwell painting representing freedom of speech is a Latino working person in Southern California? I would argue that when we’ve done that, we will have gone way beyond the crisis of Bell to do something truly creative. Thank you.

Jan. 25, 2011