Caption: C. George Peale, pictured here in his office, has transcribed, edited and published 33 plays by the 17th-century Spanish playwright Luis Vélez de Guevara. Photo: Karen Tapia Download

Caption: C. George Peale, pictured here in his office, has transcribed, edited and published 33 plays by the 17th-century Spanish playwright Luis Vélez de Guevara. Photo: Karen Tapia Download

Of Tragedies and Comedies

Scholar Illuminates Spain’s Royal Court Playwright

With a fierce look in her eyes, the voluptuous Jusepa Vaca rides horseback into the Spanish Royal Theater, lance in one hand and wolf pelt in the other, a huntress fresh from killing a wild boar. Betrayed by a captain with the promise of marriage, she seeks vengeance in the 17th-century drama, ultimately killing 2,000 men before she herself is captured and executed.

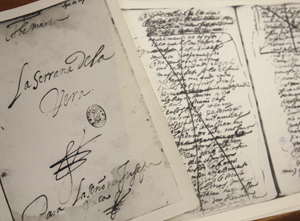

Caption: Luis Vélez de Guevara wrote scores of plays in his own ornate script. Photo: Karen Tapia Download

Caption: Luis Vélez de Guevara wrote scores of plays in his own ornate script. Photo: Karen Tapia Download

For audiences in 1613, “that was pretty racy stuff,” C. George Peale, emeritus professor of modern languages and literatures, said about Luis Vélez de Guevara’s play “La Serrana de La Vera.”

More than three decades ago, when Peale was an assistant professor at the University of Kansas, he was invited to research the Spanish playwright by the late scholar William R. Manson, an assistant professor of Spanish at the University of Arizona who had been researching Vélez de Guevara for years. Together, they pored over scores of photocopies of Vélez de Guevara's plays, most of them unpublished.

Though Manson died in 1984, Peale continued the research, involving his students since 1989, the year he joined Cal State Fullerton’s faculty.

Since then, Peale and his students have researched, transcribed from 17th-century Spanish to modern Spanish and edited dozens of Vélez de Guevara’s plays. Beginning with the publication of the first few plays in 2002, a total of 33 have been published to date. Ten more books are in the works, with five set for publication later this year.

As a tribute to Manson, the late scholar’s name appears above Peale’s on all the books. Their research efforts have been funded by grants totaling more than $300,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities and other public and private foundations.

Peale plans to send his books to Spain’s King Juan Carlos and to select theater groups and directors throughout Latin America.

He recently answered a few questions about his work.

Q: Who was Luis Vélez de Guevara?

In the 17th century, he was considered one of the three most important playwrights in Spain. Unlike the other two — Lope de Vega, the father of Spain’s national theater, and Calderon de la Barca, the Spanish Shakespeare — Vélez de Guevara never published his own plays because he was employed full time by the Royal Court. But, he was highly influential on other playwrights. One of his plays, “El Alba Y El Sol,” a drama about the beginning of the Reconquest of Spain by King Pelayo at the Battle of Covadonga, was wildly popular. It used a new poetic language, and since it was composed for a court performance, it was grandly theatrical. I’ve documented 250 performances from 1613 through 1855.

(A biography of Vélez de Guevara, written by Peale, is available for download.)

Q: How do your students help with your research and what do they learn?

I have involved dozens of students. They help me with textual research and documentation. It’s not easy work. We study old manuscripts and editions that are hard to read, but the students learn the conventions and peculiarities of 17th-century handwriting and typography, and they learn a lot about the history of the Spanish language through unmediated primary sources.

Q: How did Vélez de Guevara’s plays comment on Spanish society?

One of Vélez de Guevara's distinctive notes is his view of the Spanish Empire: his worldview is expansive and inclusive, rather than simply European. He devotes considerable space to nuanced views of Spain's enemies, be they Turks, Dutch, Germanic or Asian barbarians, Moors or Incas. He even moves Attila onto an ethical point at which the Hun gives a “to be, or not to be”-type speech. In Vélez de Guevara, the “other” gets to have his say. As a court servant, however, Vélez wrote most of his plays for pay as piecework, or, in many instances, because his works were commissioned for a specific occasion. His ideas, though original, frequently were circumscribed by his sponsor's interests. All the same, his worldview and perspective were manifestly broader than those of his contemporaries.

Q: Which play is your favorite?

“La Serrana de La Vera” is my favorite because it’s extremely theatrical and extremely dramatic. It has pathos and humor, and it’s bawdy, highly charged with eroticism and beautiful lyricism. It was written for the foremost actress of the day, Jusepa Vaca, at a time when it was scandalous for women to wear pants and ride horses, let alone hunt like men.

Q: Which play are you working on now?

“El Negro del Serafín,” which tells a fanciful version of a true story, of how the black slave named Rosambuco found redemption and freedom by becoming a “slave” of God as a Franciscan monk named Benedict of Palermo. In the play, he is killed fighting against the Turkish fleet; in real life, he died of old age.

Q: Are Vélez de Guevara’s plays relevant today?

Audiences today would be uninterested and bored by Vélez de Guevara’s historical dramas, but there are some plays that would surprise and delight modern audiences with their daring theatricality and comic originality. His social critiques were always colored by comedy. His plays are notably distinct from other playwrights of the time, so they afford us a more textured and nuanced vision of Spain's greatest period of cultural glory. What his plays give us today is another view of how Spaniards in the 17th century viewed their nation's history and traditions.

March 23, 2012