Caption: This 1939 Ellington jam session is one of the classic photos that are the subject of Benjamin Cawthra’s “Blue Notes in Black and White: Jazz and Photography.” Photo by Charles Peterson/courtesy Don Peterson

Caption: This 1939 Ellington jam session is one of the classic photos that are the subject of Benjamin Cawthra’s “Blue Notes in Black and White: Jazz and Photography.” Photo by Charles Peterson/courtesy Don Peterson

‘Blue Notes in Black and White’

Miles Davis seen as an elusive shadow in a dark room

Excerpted from “Blue Notes in Black and White: Jazz and Photography” by Benjamin Cawthra

A hot night on Broadway, Aug. 26, 1959. Club patrons have sought the city’s sidewalks to take the air during a break in the music, and soon there is trouble.

Caption: Benjamin Cawthra. Photo by Karen Tapia

Caption: Benjamin Cawthra. Photo by Karen Tapia

Traffic on the busy sidewalk between 52nd and 54th Streets has stopped, and at least two hundred people quickly gather, fanning out from a dark awning marking the entrance to Birdland, the “jazz corner of the world,” and spilling onto the street between parked cars and beyond. As automobile horns sound, an altercation between a white police officer and a black male in front of the club is underway. From a second story rehearsal space across the street, there is a better view, and a big band stops its run-through to check out the spectacle. “We couldn't hear our own music [due to the noise],” said the bandleader Earl Hodges. Moving a boom microphone to the window, the group recorded the piercing sound of sirens and voices shouting with what a reporter called the “harsh, bitter voices of fighting men.”

“Take him to the precinct … Get that … out of here.”

“I'll punch him right in the nose, so help me.”

“Why don't we all go to the precinct. I saw what happened. Let's go.”

“That ain't no police … He ain’t police.”

“Okay, break it up. Move along, it's all over.”

Emerging from the crowd in handcuffs, blood staining his light-colored sport jacket, jazz trumpeter and bandleader Miles Davis clambers into a paddy wagon and heads for 54th Street Precinct, where he will be booked for felonious assault upon a patrolman and disorderly conduct. Forty members of the crowd follow on foot.

Davis had been performing in the club for an Armed Forces Radio broadcast and had come up to the street to escort a "pretty white girl named Judy" to a cab between sets. Stopping for a smoke at the southwest corner of 53rd Street near the club entrance as fans and other pedestrians milled about or moved through, Davis encountered Officer Gerald Kilduff, walking his beat. Kilduff asked Davis to move along to keep the sidewalk clear.

“I’m working right here,” Davis replied, pointing to his photograph next to the club entrance and his name on the marquee. Davis refused to move after another order, and Kilduff attempted to place him under arrest. Davis resisted, grabbing Kilduff's nightstick to protect himself. Kilduff had pushed Davis against a parked car when plainclothes detective Donald Rolker appeared and began beating Davis on the head with a black jack, in the trumpeter's words, “like a tom-tom.” An “angry crowd … mostly colored people," according to Rolker, threatened the officers as Rolker hit Davis perhaps fifteen times. One eyewitness, Elaine Smith, was so upset by Rolker's actions that she hit the detective herself. Six newly arriving police sirens drowned out the angry screams of the crowd, leading to its dispersal. Across the street, Hodges stopped the tape after four minutes, and the band went back to work.

• • •

Always immaculately dressed, with clothes altered specifically to enhance his profile while playing the trumpet, Davis performed music as though it was a private art to be appreciated and enjoyed by audiences sophisticated enough to attend a performance. True to his aesthetic attitude as a modernist, Davis did not bother to introduce tunes, often segueing from one “untitled” composition to another without a break, as if it was up to the audience to find the meaning for themselves.

“What am I supposed to do? Get up there and say, ‘And for our next number we will play the ever popular … ?’ If they don't know what it is, what difference does it make?”

Davis became the epitome of the aloof jazz musician performing not for applause but out of some kind of artistic need or racial pride, depending on the interpreter. In fact, he combined these elements and reinforced them through his verbal silence on the bandstand.

Dennis Stock’s photograph of Davis performing while facing away from members of the audience in 1957 is an example of his ability to appear posed during performance while projecting an aloof attitude, as are rare television appearances such as The Sound of Miles Davis broadcast in 1960 and a concert recorded on Swedish television in 1967. Stock builds upon Herman Leonard's precedent, capturing the backlit smoke and rendering the artist as a singular genius, but Stock's Davis photographs add new elements to the construction of black jazz hero. Shot from a low angle as Leonard's were, Stock's pictures actually include the audience in the frame, extending the sense of the performance as a communal event. And yet the performer, surrounded as he is by the audience, seems even more remote and unknowable. Stock's Davis seems withdrawn and unapproachable as he occupies a visual plane distinct from his listeners, even though he appears to be performing at ground level rather than on a stage. He is less a tactile sculpture than an elusive shadow in a dark room.

Reprinted with permission from the University of Chicago. Copyright © 2011 by the University of Chicago Press.

Oct. 28, 2011

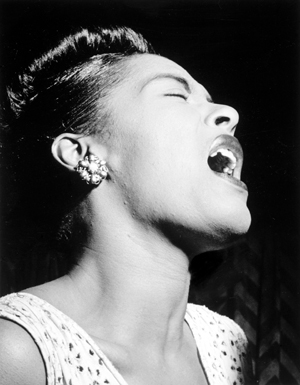

Billie Holiday, circa 1948. © William P. Gottlieb / jazzphotos.com

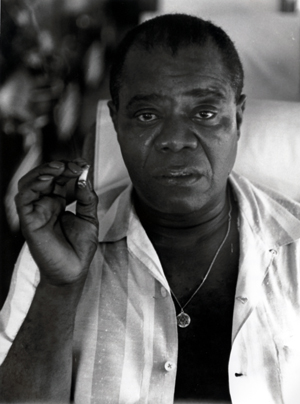

Billie Holiday, circa 1948. © William P. Gottlieb / jazzphotos.com Louis Armstrong, June, 1960. Photo © Herb Snitzer

Louis Armstrong, June, 1960. Photo © Herb Snitzer