Volcanologist Uses Local

Mountain Range As Geological Laboratory

Brandon Browne’s research takes

him all over the world. His latest focus is Mammoth Mountain

which hasn't erupted in about 50,000 years.

December 1, 2005

By Laurie McLaughlin

As they hop-scotched their way across

Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula via helicopter

en route to explore and study Kizimen volcano — last

active in 1928 —Brandon L. Browne’s team landed

to refuel near another volcano, Karymsky, which had periodically

erupted since 1996 and is located about 80 miles south of

Kizimen.

“We desperately needed fuel, so the pilots

decided to make a quick stop. Soon after we landed, however,

we all heard an explosion. I looked up and saw an eruption

of ash and debris from the summit. We all were amazed and

petrified at the same time,” says Browne, assistant

professor of geological

sciences, who joined the faculty this year. The July 2002

explosion he witnessed at Karymsky was the closest he’s

ever been to a volcano in the throes of an eruption.

Browne is a volcanologist, and every volcano

he experiences, long dormant or not, is of interest to him.

Even this one, which he admits — at one-quarter of a

mile away — was a little too close for comfort, was

a thrill. “It felt similar to the first few seconds

of an earthquake,” he says, “where every sensory

preceptor in your body is electrified, and you become acutely

aware of every little thing around you.”

There are only about 1,000 volcanologists worldwide,

and while mountains have been erupting since the beginning

of time, says Browne, “volcanology is a very young science.

A lot of people study volcanic rocks, but few people actually

study volcanoes from the perspective of trying to understand

how volcanic eruptions occur. Fortunately, the field of volcanology

is one of the most rapidly growing in the geosciences.”

Browne’s research focus is to understand

how ash, rock and other debris that erupts from volcanoes

are transported and deposited in the surrounding landscape.

“With this information, authorities are better able

to plan for hazards in the event of an eruption,” he

says. His research has taken him around the world to both

dormant and active volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest, Japan,

Russia, Mexico, South America and Alaska, where he earned

his doctorate at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

One can’t help but notice, however, that

Browne is now in Fullerton, and there are no volcanoes in

Orange County.

“The closest volcano that I’m working

on now is Mammoth Mountain, which hasn’t erupted in

about 50,000 years,” he says. Browne already has traveled

up to the mountains on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada

range this semester with a group of CSUF students.

“First, we plan to look at how volcanic

eruptions at Mammoth were triggered, and second, we plan to

determine the time span between the triggering event —

which typically occurs deep in the crust — and the eruption

of magma at the surface,” he says. “For most volcanoes,

this time span ranges from a few days to many months. Data

from our research will allow local authorities in Mammoth

Lakes to know how much time they have before an eruption is

likely to occur in the future.”

No two volcanoes behave in exactly the same

way, adds Browne. “They are like people. Each one is

different, and you have to figure out their personalities

to know what they’ll do.”

«

back to News Front

|

Gareloi Volcano on the Aleutian Islands, Alaska,

blows some steam during a visit to the site by

Brandon Browne, assistant professor of geological

sciences at Cal State Fullerton.

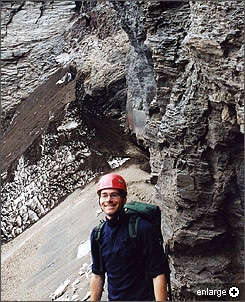

Brandon Browne explores volcanic sites at Aniakchak

National Park, Alaska.(2/6)

Volcanologist Brandon Browne hikes his way towards

Mount Hood, a volcano located near Portland, Oregon.

The Cal State Fullerton faculty member is among only

about 1,000 volcanologists worldwide. “Fortunately,”

he says, “the field is one of the most rapidly

growing in the geosciences.” (3/6)

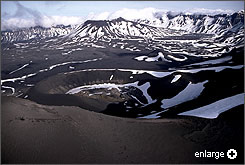

Redoubt Volcano, Alaska — one of the volcanic

sites that Brandon Browne has visited as part of his

study into how debris is transported and deposited

in the surrounding landscape. (4/6)

Aniakchak Volcano on the Alaskan Peninsula. As one

of only about 1,000 volcanologists worldwide, Brandon

Browne studies volcanoes to understand how eruptions

occur. (5/6)

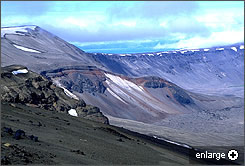

A view of volcanic slopes in Aniakchak National Park,

Alaska. Brown studies volcanos to understand how ash,

rock and other debris that erupts from volcanoes are

transported and deposited in the surrounding landscape.

(6/6)

|

| Get Expert Opinions On... |

|

|

|

|